Serious, substantive, sobering. Alas, we’re not referring to any of this year’s presidential contenders, but to the thoughtful talk of economics, markets, and investments that dominated the 2016 Barron’s Roundtable. Turbulent times demand such an appraisal, and that’s what our nine investment panelists delivered in spades.

Optimism was in short supply at our annual gathering, held last Monday at the Harvard Club of New York, probably owing, in part, to stocks’ horrific swoon the prior week. Opinions were as plentiful as troubled energy bonds, however. Broadly speaking, these Wall Street luminaries see more stock market turmoil, junk-bond mayhem, and global strife in the year ahead. They also see Hillary Clinton winning the White House—except for those who think the vote will go to Donald Trump.

Photo: Brad Trent for Barron's

Some ’round the table expect U.S. stocks to end the year flat or down, while others see modest gains on the order of 7%. Nearly all agree that judiciously buying undervalued equities will yield far greater returns than sticking with index funds. Our panelists expect the U.S. economy to expand only modestly this year, by a bit more than 2%, while China’s economy will continue to struggle, leading to further devaluation of the Chinese currency and continued pressure on commodities and emerging markets.

The group thinks the Federal Reserve, which finally lifted interest rates in December for the first time in seven years, won’t hike four more times during 2016, notwithstanding its stated intentions. That’s because market conditions simply won’t allow it. Indeed, Fed Chair Janet Yellen might even be forced to ease again after lifting rates one more time, says Jeffrey Gundlach, one of the world’s best bond investors, co-founder of Los Angeles–based DoubleLine Capital, and a newcomer to the Roundtable. The other fresh face in the crowd is that of William Priest, CEO and co-chief investment officer of New York’s Epoch Investment Partners, who boasts a long and successful record of mining macroeconomic trends to identify smart investments.

Gundlach is bracingly bearish, Priest only slightly less so. Brian Rogers, however, chairman of T. Rowe Price and one of this week’s two featured stockpickers, is an optimist by nature. These days, he is buying shares of companies that have been excessively punished by investors, and that sport healthy dividends and strong financials. American Express (ticker: AXP) and Macy’s (M) are high on his list.

Oscar Schafer, chairman of Rivulet Capital in New York, is also a stockpicker, who bargain-hunts among mid- and small-cap names. He notes that the market’s smaller fry have been in a stealth bear market for the past year, even as the Facebooks and Amazons of the world have gone to the moon. Yet Oscar likes the prospects for three smaller stocks, including Calpine (CPN), the merchant power producer, which he highlights in this week’s Roundtable issue, the first of three.

Barron’s: Happy New Year, everyone. It has been a great year so far, if you ignore the stock market, the economy, the Middle East, and anyone running for president. Let’s start with the outlook for the economy. Mario, what lies ahead?

Gabelli: The consumer accounts for 70% of the U.S. economy, and is doing well. Wages are rising, jobs are increasing, and consumer balance sheets are OK, even after the decline in the stock market in the past three weeks. Automobile sales will flatten this year, the consumer will spend, and housing is improving. Consumer outlays for food and fuel will continue to decline, at least through the fall. Congress has passed an infrastructure bill and a tax bill. We’re finally spending more on the military. We will have to deal with the cost of government entitlement programs, and a strong dollar is having a negative impact on exports. But, overall, the U.S. economy could grow by 2% this year.

How do things look in other parts of the world?

Gabelli: ln Europe, Mario Draghi [president of the European Central Bank] has stimulated the economy, and things will continue to improve. In China, the consumer economy, which accounts for about 40% of the total, could grow by 10% a year in the next five years. The balance of the economy will grow at a 3% to 4% rate, and has challenges. I like what India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, is doing. I like what is happening in Japan. But I don’t have much optimism for most Latin American economies.

What is your view, Bill?

Priest: There are only three drivers of stock-market returns: earnings, price/earnings multiples, and dividends. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index was up 72% from 2012 through 2014, and 56% of that gain came from P/E multiple expansion. Quantitative easing [central-bank asset-buying programs aimed at driving down interest rates] has been the driver of valuation metrics, and that is ending in the U.S. and United Kingdom, and isn’t going to have much more of an effect in Europe or Japan. That means P/Es will be flat or down from here. Earnings are problematic, as well. Many companies are having difficulty generating revenue gains, and profit margins will be under pressure. Dividend yields will rise, but the growth rate will be less than in the past. Markets will struggle this year to appreciate both globally and in the U.S.

2 Stock Picks from Brian Rogers

The chairman of T. Rowe Price makes the case for American Express and Eaton Corp., both selling for around 11 times earnings.

Larry Summers [a Harvard economist and former secretary of the Treasury] has called the current economic environment one of secular stagnation, and that is an accurate description. It means 2% growth is the new 4% in the developed world. Most of the 34 countries in the OECD [Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development] have an inflation rate below 1%, which presents challenges for policy makers. The issue with China is one of contagion: As the Chinese economy slows, materials producers such as Brazil and Australia will suffer, as will China’s trading partners in the Pacific Rim. In Europe, Germany has a bad cold, and everyone else will feel it.

Brian, what do you expect?

Rogers: I agree with much that has been said. Growth is challenged, and it all goes back to the global financial crisis. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff called it in their book This Time Is Different: When you work your way out of a global financial crisis with a lot of leverage, growth is difficult to achieve. We could be looking at growth of 2.25% in the U.S. this year. Europe is improving, and the only thing we know about China is that the government exaggerates economic statistics. If they say the economy is growing by 10%, it isn’t.

When will the economy finally emerge from its post-financial-crisis funk?

Rogers: We’ll get out of postcrisis mode probably in 2017 or 2018. People are still working through personal financial challenges. One sign of this is that investors haven’t regained their animal spirits, even after an extraordinarily long period of slow growth and decent market returns. The individual investor doesn’t really have confidence in the market and is willing to earn one basis point [one hundredth of a percentage point] in a money-market fund.

Black: To repair the economy, we need structural changes in public policy. From 2009 to 2014, gross domestic product grew by an average of 1.4% a year. The normalized postwar rate is 3%. We have had no bipartisan consensus on fiscal policy since President Obama came into office. We need a huge tax-policy overhaul to bring jobs back to America. We need investment tax credits for manufacturers, and a major infrastructure program. Most politicians are appealing to our animal spirits. They are not discussing public policy. This means we will continue to have low nominal GDP growth of 2% to 2.5%.

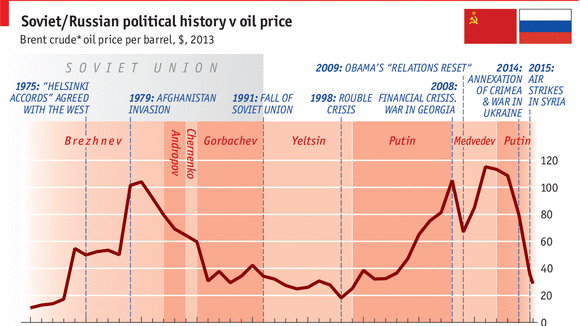

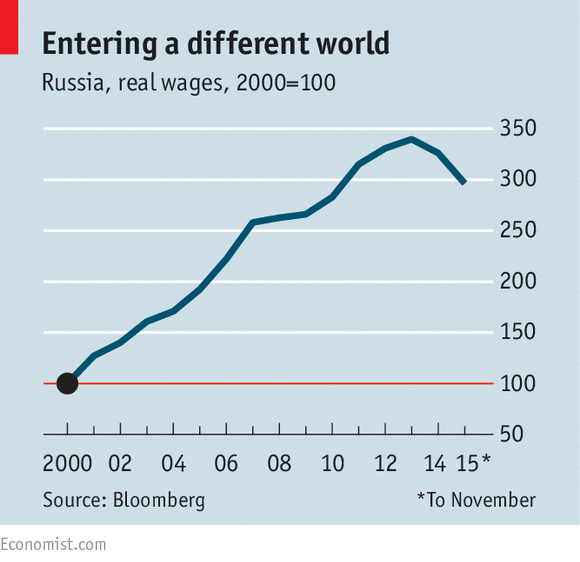

Gundlach: There is no conversation about these issues. Democracy is government by crisis. Things go along until suddenly there is a call for change. One fundamental problem is demographics. In the U.S., the ratio of people working to those who are retired or want to retire isn’t that bad right now. But things are different around the world. Japan went into a demographic tailspin 20 years ago. China now is where Japan was then. Italy will lose a third of its labor force in the next generation. Russia is on the verge of the greatest implosion of population in the history of the world, absent famine, war, or disease. If you have fewer people working as a percentage of the population, you need that much more economic growth from those who are productive. In the U.S., this issue manifests itself in government policy through entitlement programs. We’re in a fairly level place until 2019 or 2020, but then the moment will come when we realize we can’t keep these programs in place.

Oscar Schafer’s Hidden Gem

The chairman of Rivulet Capital and Barron’s Roundtable veteran thinks the market is missing the earnings power of transaction processor Evertec because it’s based in Puerto Rico.

One thing you can rely on is that growth estimates at the start of the year will be marked down. The World Bank just downgraded its 2016 forecast for global growth to 2.9% from 3.3%. I’m a bond guy, so I look at Fed policy. A zero interest-rate policy for seven or eight years motivated a lot of behavioral changes among investors and led to malinvestment. That is one reason the market’s P/E ratio expanded. In 2012, when I was launching a fund and seeking 7% returns, many financial planners were promoting master limited partnerships as a way of getting a fat yield without taking bond risk. What a disaster: MLPs are down because they were leveraged to energy prices. This is the backdrop to my thinking.

Zulauf: Coming back to the question of when secular stagnation ends, it could last for the next 15 or 20 years. It relates in part to demographics. We’ve had three demographic waves propelling the world economy: The baby boomers went to work, Eastern Europe joined the world economy, and China joined the world economy. That’s all over now.

Another issue is debt. The world economy has levered up since the early 1980s, and economic subjects have hit their borrowing-capacity limits. By definition, that means lower demand. Also, regulation has increased dramatically in the past 15 years, and the trend is toward even more regulation. That is a restraining force on growth. Finally, bad economic policies have focused for decades on demand stimulation. We can’t change demographics. We should restructure debt, reduce regulation, and pursue sounder policies. But none of these issues is being discussed or addressed. That’s why secular stagnation will linger.

The Roundtable panelists look for stocks to outperform bonds and the U.S. to beat most other markets in 2016. China’s woes could keep the pressure on emerging markets. Photo: Jenna Bascom for Barron's

Listening to all of you, a contrarian might well assume the economy is on the verge of a boom.

Zulauf: Contrarians aren’t always wrong, but they aren’t always right, either.

The U.S. has the best demographics of all the industrialized nations. But what the U.S. housing market was to the world economy in the last cycle, China is in the current cycle. China has a major balance-of-payment crisis, which most experts don’t understand. A balance-of-payment crisis ends with a recession. China’s currency is heading south. The only way to prop it up is to restrict capital flows, but that would create another bubble inside China, leading to even bigger problems. China eventually will let the currency fall in value.

Gabelli: Felix, why not let the currency fall now?

Zulauf: That is the best solution, but a decline of 15% to 30% from here in the value of the yuan has negative implications not just for China’s trading partners but its competitors around the world. China is the world’s largest exporter, and one of the largest importers. Imports will be cut if the currency falls sharply, and prices of exported goods also will go down. We are talking about a major deflationary hit to the world economy. That leads to lower corporate revenue and profits outside China, forcing companies to cut costs. Then you have a global recession. That’s what the whole situation is leading to.

Gundlach: People come to believe things simply because of repetition. They have come to believe that China can grow by 7.5%-plus every year because that is what has happened in the past, at least according to Chinese statistics. They think the government, being autocratic, can push a button or pull a lever every time growth slows, and get growth back up to 7%-8%. Why are we all extolling the virtues of free-market capitalism? Let’s get an autocrat in place and get the U.S. growing by 8% a year.

Gabelli: Just be patient.

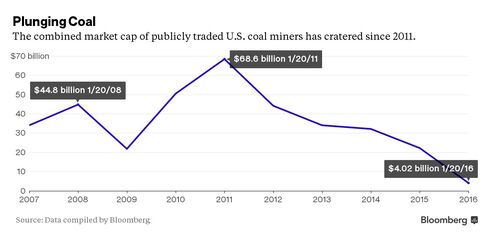

Gundlach: People also believe, because of repetition, that inflation will stay at these low levels forever. Based on the price of Treasury inflation-protected securities to ordinary bonds, the market is forecasting inflation of 1.75% for every year from year three to year 30. That’s just not logical. China is growing much more slowly than it admits. That is the message of the market. China represents nearly 50% of global demand for copper, steel, and aluminum, and 70% of demand for coal.

Cohen: Excuse me, did represent.

Gundlach: Exactly, because they are buying less today. Commodities prices are falling every day. That can only be because Chinese demand is weak. Prices for copper and iron ore have been cut just about in half.

Felix Zulauf, right: “The median stock in the S&P 500 was down 22%. But stealth bear markets always turn into real bear markets. That’s how bear markets start.” Photo: Jenna Bascom for Barron's

Priest: Oil was down 35% last year. It has to be demand-based.

Witmer: The drop in oil is supply-based.

Cohen: Over centuries, the trend in commodity prices has almost always been down because of capacity additions and technological advances. In shorter time frames, supply-and-demand issues influence prices. To Meryl’s point about excess oil supply, there was an excess in capital expenditures in the oil industry, much of it in the U.S., but elsewhere, too.

I see this year as one of divergences. The U.S. has demographic advantages, and has rebuilt its financial system sooner than many other industrial economies. Also, U.S. consumers are feeling better, and balance sheets have been repaired, except with regard to subprime auto loans and student debt. The risks to the global economy aren’t so much the mathematics of what is happening in China, but the psychological impact not just on portfolio managers but business managers. Just 1% of U.S. sales are exposed to China. As the year progresses, investors will have a better understanding of how the U.S. is performing, relative to other economies.

What is your forecast for GDP growth?

Cohen: Something between 2% and 2.5% sounds about right. My colleagues at Goldman Sachs have a forecast of 2.2% growth, a little below the consensus. Keep in mind the absence of some negatives. We had enormous fiscal drag for three or four years. This year, that will be neutral to slightly positive. Also, the sharp decline in energy capex was an enormous drag. If it doesn’t get weaker, by definition, it’s a net positive.

S&P 500 earnings were hit last year by two factors: currency-translation losses and the sharp decline in energy prices. The dollar has been going up since the middle of 2014. On a trade-weighted basis, it is up about 30%. Will it go up another 30%? Not likely. That means currency-adjusted corporate earnings won’t take the same hit. Energy-industry earnings also declined sharply, and that probably won’t happen again to the same degree.

Zulauf: This is a strange thing. People say S&P earnings are better than reported if you don’t include the energy sector. But all other sectors benefited from lower energy prices.

Gundlach: It’s like an underperforming portfolio manager saying to a review committee, “If you take out the stuff that was down, we were up.”

Rogers: Or like a company reporting earnings before expenses.

Cohen: I want to go back to Bill’s point about P/E multiples. With the S&P 500 trading at roughly 16 times this year’s expected earnings, it might not be sensible to argue for additional multiple expansion. Thus, it becomes critical to look at earnings, profit margins, and return on equity.

Priest: Interestingly, from 2008 to 2014, and maybe to 2015, the U.S. was the only source of earnings gains in the developed world. Industrial-production measures for the developed world have been flat since 2008. The only growth in production was in the U.S. To Jeff’s point, China was the marginal buyer of everything, and suddenly it stopped. The collapse in commodities prices and sales volumes is still feeding through the system. I’m not sure what the bottom is for some of these commodities prices, but quite possibly, we haven’t seen anywhere near the bottom yet.

Zulauf: We likely don’t understand fully how big the Chinese investment and credit boom was. During its three best years of economic growth, China consumed as much cement as the U.S. in the past 100 years. It’s mind-boggling. If the yuan falls by 20%, it will have a tremendously deflationary effect on the world, and all the numbers you mentioned today will be wrong. You can’t escape the bust after the biggest boom mankind has seen.

Cohen: The Chinese government has publicly recognized that it must deal with issues of environmental quality and government transparency, which also relate to the economy. I’ll let others talk about the transparency issue, but when the Chinese government admitted at the recent Paris Climate Conference to an environmental problem, that was an enormous directional change. The U.S. economy is roughly twice as large as the Chinese economy, yet China emits 60% more carbon dioxide. China has some of the dirtiest air in the world, and half its water supply in several provinces is too dirty for industrial use. Eighty percent is unusable for drinking, washing, and agricultural purposes.

Zulauf: The people are rebelling. China didn’t agree to the climate-change deal in Paris because other nations asked it to, but because the Chinese people are dissatisfied with the quality of the air and water. The government has to do something about it.

Oscar, where do you see the economy headed?

Schafer: The consumer is in good shape. Companies outside the energy sector are doing well. What worries me about the economy is the possibility of a wild-card event, such as a chemical-weapons attack against a civilian target in Europe. The economy will grow a little bit this year.

Meryl, we haven’t gotten your view.

Witmer: As you know, I try to stick to stock-picking. Companies tell us there isn’t a lot of growth out there. There is no driving force to move things forward. The fracking boom was great for the economy until it ended. It helped move things forward. Housing is OK. Auto sales are probably at a peak. With the dollar so high, many companies are having trouble exporting their goods. The outlook isn’t rosy. It’s just OK.

Brian Rogers: “As an asset allocator, I ask myself, Can you invest in a portfolio of businesses whose value will accrete by more than 3% a year? That is my expected bond yield, and the threshold for an equity investor.” Photo: Jenna Bascom for Barron's

Gundlach: What I find remarkable is the contrast in central-bank policies between the U.S. and Europe when there is only a 60-basis-point difference in GDP growth rates. It’s like a parallel universe. Economic growth here is trending sideways to down. European GDP is trending higher. The U.S. growth rate is 60 basis points higher now, but maybe in two quarters we’ll be growing at the same rate. Europe has negative interest rates and is talking about expanding QE. We are raising rates and tightening credit conditions, first by eliminating quantitative easing. As of June 2014, everything changed. That’s when emerging markets and commodities started to crash.

Nominal GDP is a fantastic indicator of bond yields, on a secular and short-term basis. Nominal GDP is very low, and might be headed toward 2%. The Fed has raised interest rates 118 times since 1945 or so. On 112 occasions, nominal GDP was higher than 5.5%; it averaged 8.6%. Twice since the 1940s, the Fed has raised rates with nominal GDP below 4.5%. The last time they did so was in 1982. They had to reverse course almost immediately.

Schafer: They never raised rates when the ISM [Institute for Supply Management index of business conditions] was below 50, as it is now.

Gundlach: That’s true. It is unprecedented for the Fed to be raising interest rates with nominal GDP at or near 2%. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta publishes something called GDPNow, which forecasts real GDP [adjusted for inflation] every day. It is at 1% now.

Cohen: I see one enormous difference between the U.S. and Europe: U.S. financial institutions are in a much stronger position relative to their European counterparts. There hasn’t been the same sort of balance-sheet adjustment in Europe, and that could make European institutions much more vulnerable to economic shock, management error, and so on. Also, while the Federal Reserve has tightened, conditions aren’t really tight. Interest rates remain extremely low. We can argue about nominal versus real growth, but the boost in rates hasn’t had a negative impact on credit-sensitive sectors, such as housing and autos.

Rogers: We have to get away from the notion that we are in a massive tightening cycle. We had seven years of basically zero rates. The Fed has moved once. No capital-spending decisions are being influenced by a 25-basis-point rise in the cost of capital. If anything, the Fed was late. It probably should have lifted rates for the first time when GDP growth was at 3%, 12 to 18 months ago.

Gundlach: Things would be worse now. Raising interest rates can’t make things better. On Sept. 17, the Fed didn’t raise rates, despite widespread expectations. A key reason it demurred was because the Fed governors thought global financial conditions looked too rocky. The EEM [ iShares MSCI Emerging Markets exchange-traded fund] closed on Sept. 16 at $34.55. Yet, on Friday [Jan. 8], the price was $29.51. Emerging market debt is 3% lower since Sept. 16. Bank loans have fallen 4%. The S&P 500 is down. The dollar is up 3%. Ten-year Treasury yields have fallen by 17 basis points. The CRB commodities index is down 15%, and oil is down 35%.

Your point?

Gundlach: If conditions were too rocky to raise rates on Sept. 17, why are we talking about raising interest rates four times this year? The investment forecast with the highest probability of success is that the Fed won’t raise rates four times this year.

Zulauf: Central bankers have no clue about what’s going on in the world. They had no clue that markets would be so ugly in January, and they don’t understand what the situation in China means for the rest of the world. I am not an admirer of zero-based interest rates, but the timing of the Fed’s rate hike was completely wrong. They didn’t raise rates based on the facts, but because they felt they needed to do so.

Black: If you look at companies on a case-by-case basis, the industrial economy is rolling over. We have a bifurcated economy. On the consumer side, personal income, retail sales, and the savings rate are all in the plus column.

Gundlach: Retail sales are up simply because of auto sales. Ex-autos, the number is negative.

Black: But we added 2.5 million jobs last year. Across the board, things look good. On the industrial side, however, new factory orders and rig capacity utilization are rolling over. There is no earnings momentum. As an investor, you want to buy companies with sustainable earnings power. But that is difficult because the industrial sector is in bad shape. Fed Chair Janet Yellen had to put a positive spin on her speech about the U.S. economy after she raised rates in December, but had she looked at industrial companies, she would have seen that they aren’t doing well.

Abby Cohen: “My colleagues have a year-end price target of 2100” on the S&P 500. Photo: Jenna Bascom for Barron's

Priest: When you walk into an auto dealer’s loan office, you take out a 78-month or 84-month loan and they give you a car. In many ways, there is more debt outstanding today on a global basis than in the past. The gross amount of debt per dollar of GDP is way up. Rates are low, so it is easy to service that debt, but it was the extension of credit that allowed for real GDP growth. One reason retail spending isn’t as high as expected is because people have to pay down this debt.

Gabelli: In the sharing economy, you don’t need to own a car, thanks to the Ubers of the world. Across industries, all sorts of structural changes are going on.

Cohen: What is the impact of these changes on the economy? It is entirely possible that government data on retail spending are incorrect, in part because so much is happening online. We might be mis-measuring productivity and capex and GDP, as well. Our economy is undergoing a major shift, as industries incorporate digital technologies, whether in health care, auto production, or many other industries. Sometimes, investments that we might think of as capital spending get counted as operating expenditures. To borrow an example from Michael Porter at Harvard Business School, when Amazon.com [AMZN] decides to build its Amazon Prime business at a loss because it wants to attract new Amazon shoppers, is it really a loss, or a form of 21st century capital spending?

With regard to China, the gap between the published data and reality could be as much as two percentage points. But there are also gaps in our data systems because our data systems haven’t kept pace with the structural changes in our economy.

So, if we were counting things correctly, how fast would the economy be growing?

Cohen: I don’t know for sure, but some studies suggest an additional one-quarter to one-half percentage point of growth.

Let’s go back to interest rates. What is your year-end forecast for the 10-year bond, Jeffrey?

Gundlach: I had strong views on the 10-year for ’14 and ’15. In 2014, I was sure rates would fall. In 2015, I thought they’d go nowhere. This year, there could be a big move in interest rates, based simply on the coiling action of the market. The 10-year has been trading in a narrower range. It yields 2.17% now, exactly what it yielded at the end of 2014. From a chart perspective, there could be a significant move. While I don’t have nearly the conviction that I had in 2014, I’d say the yield on the 10-year is going up.

How can I predict that when I don’t expect the Fed to raise rates, commodity prices are low, and the junk-bond market is in turmoil? U.S. interest rates have been rising for several years. Treasury yields bottom gradually, then suddenly. We are in the gradual phase now. The two-year Treasury bottomed almost five years ago at 15 basis points. Five- and 10-year Treasuries bottomed in July 2012. The 30-year Treasury bottomed a year ago. One reason rates could rise in this environment is because of liquidation [of Treasury bonds] by foreign holders. People have been worrying about this for the past 15 years. Liquidation by central banks and sovereign wealth funds seems to be overwhelming the flight-to-quality demand for Treasuries.

When I called for lower interest rates in 2014, I gained some new friends among the doom-and-gloom crowd. When I said interest rates would rise last January, they felt betrayed. But my base case isn’t a deflationary bust. My guess is interest rates will move higher in 2016 without a lot of conviction. The Fed will be less likely to raise interest rates in a sequential fashion because the markets, particularly the junk-bond market, are throwing a fit.

If you own a broad bond-market index fund, will the rise in yields be enough to offset the loss in bond prices?

Gundlach: Last year, rates rose a little, and investors earned around 50 basis points in a broad bond index. The rise in yields was so little at the low end [among short-term bonds] that it saved the market from a negative return. But the duration of a total bond-market index is 5½ years. If rates rise by 40 basis points, which is possible, it would take away all the gain.

Priest: What do you think the yield curve will look like this year?

Gundlach: If the Fed does what I think, the curve will steepen. When the Fed tightens, the curve reliably flattens. Financial conditions started tightening in June 2014, and the yield curve has been flattening ever since.

Priest: A flattening yield curve is death for certain types of financials. You are seeing that in the stock market today, with financials selling off.

Gundlach: That’s because the Fed hasn’t dialed back its rhetoric about four rate hikes this year. Here we have the worst first week of the year in history for stocks, and two Fed governors have come out and said, “We’re on track for four rate hikes.” This is why the markets are in trouble. Underlying positive fundamentals aren’t there. Junk bonds are really in trouble. The junk-bond ETF [ SPDR Barclays High Yield Bond ETF/JNK] is trading at a lower price now than three weeks after Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in 2008. Think about how the world was feeling then.

I expect the Fed to hike early in the year and then ease. It will go up, then down. But the Fed needs to dial back its rate-hike rhetoric because the markets are throwing a fit. The question is, how long will this take, and how much more will junk bonds have to suffer? The junk-bond market will be populated increasingly by EMM—energy, materials, and mining issues. Even if oil prices stage a major rally to $40 a barrel, the clock will run out on a lot of energy companies.

A huge percentage of North American energy companies are losing money. We are going to see an incremental rise in defaults, and triple-B, and even A-rated companies will be downgraded by credit-rating agencies. We have already seen a significant turn in the upgrade/downgrade ratio as more corporate bonds get downgraded. Troubled sectors could go from 20% of the junk-bond market to perhaps 35%. Probably the worst investment is a junk-bond index fund, because it will get overexposed to defaults. Simplistically, the junk-bond market is a bet on oil. If you are betting on oil, then bet on oil. If your thesis for owning junk bonds is that oil is going back to $70, buy oil!

Rogers: Junk bonds can be great investments. But junk bonds and ETFs aren’t made for each other.

Cohen: Brian, wouldn’t you agree that most bonds and ETFs aren’t a good blend?

Rogers: Many things and ETFs don’t match, but I digress. Going back to interest-rate guesstimates, we won’t see four rate hikes this year. The Fed will act twice, because it isn’t going to act only once. It wasn’t “December and done,” unless there is a material downturn in the world economy in coming months. The yield on the 10-year Treasury will approach 3%, which means you’ll probably lose 3% or 4% on the bond. I see a gentle upward move in rates, with the federal-funds target [the rate banks charge one another on overnight loans of funds maintained at the Fed] moving up to 0.75%-1%. That’s two hikes from here. The Fed has never hiked once and then stopped.

Zulauf: There are many things that never happened that are happening in this cycle.

Cohen: The Fed’s rhetoric has been far more nuanced than people seem to think, even if you examine Janet Yellen’s statement in December when the Fed first raised rates. The Fed made it clear that anything it does in the future will be data-dependent. Its actions will depend in large part on how the labor markets are performing. As December’s terrific jobs report shows, the labor market is getting better. Household incomes are rising, and the savings rate was up to 5.2% in the latest reported quarter.

We don’t fully understand the consequences of the negative interest rates we’re seeing in many countries. It is one thing for this to last a short period of time, but negative rates in much of Europe and elsewhere have peculiar effects on individuals and corporate decision-making. The Fed is trying to move to a more normal level of between 0.5% and 1% on the fed-funds rate, based on the economic data. That might not be such a bad idea, given that the zero-limit bound is something we don’t have much experience with, especially on an extended basis.

Schafer: I have no great view on interest rates. But low interest rates are like the shot clock in basketball. Before the shot clock, you could delay and delay a game. Once it came into use, you had to make decisions. With low interest rates, there is no opportunity cost for companies in doing nothing. Thus, rising interest rates would help the economy in a way.

Priest: I see only one more rate hike coming, because the world isn’t in great shape. If you consider whatHoneywell [HON], 3M [MMM], and Staples [SPLS] said when they reported earnings for the latest quarter, all were pretty darned negative. They all lowered expectations. The first two are global companies, and Staples is the largest office-supply retailer in the U.S. None of them said life is getting better. I heard a great definition: The plural of anecdote is data. Now you have data about the global economy. This year is going to be remarkably disappointing for real growth.

Zulauf: I’m the odd guy out here. I say the Fed won’t hike rates this year because the economy will surprise on the soft side. Therefore, it doesn’t make sense to lift interest rates. It is clear that the Federal Open Market Committee [the Fed’s policy-making committee] wants to return to normalcy on the rate front, but circumstances pose a problem. I agree with Jeffrey that some foreign central banks are selling large quantities of Treasuries to support their currencies. It isn’t just China, but the Saudis and Omanis and some others, too. These sales are being felt in the Treasury market; that’s why bond yields didn’t fall as much as you might expect, given what has happened to commodities prices. It tells you the downside potential in yields is probably limited.

However, there is a trade here. Yields could first fall on 10-year and longer-dated Treasuries, but then rise again, because later in the year the U.S. dollar could have a big correction against the euro, and maybe even the yen. It is going to be a tricky year. The bottoming process in yields and interest rates could stretch out for another few years.

Cohen: The decline in energy prices has put pressure on the current accounts of energy exporters. But some countries might benefit from it. Doing a back-of-the-envelope calculation, today’s energy prices could produce a net benefit of about $100 billion for China. That’s not chicken feed.

Zulauf: China’s current account is probably running a surplus of $300 billion or so. But what counts in the current situation is the capital account, which is running a deficit of roughly $1 trillion.

What does all of this mean for the performance of stocks in 2016?

Black: The market is going nowhere this year.

Gabelli: From Friday’s close, or from Jan. 1?

Black: From Jan. 1. The S&P 500 finished last year at 2043.94. Analysts expect S&P 500 companies to post earnings from operations of $125.56 in 2016, up from an estimated $106.39 last year. That implies 18% growth, which isn’t in the bag. I see 4% growth in earnings per share from net income and 3% from stock buybacks, which takes you to about $114. Based on Friday’s S&P close of 1922.03, the market is trading for 16.9 times estimated earnings. By historical standards, the market is slightly overvalued.

Many of us specialize in small- and mid-cap stocks, which did very poorly last year. As homogeneous risk classes, both are still expensive. The mid-cap Russell 2500 index is trading at about 21 times expected earnings, and the small-cap Russell 2000 is at roughly 22 times. It is hard to find great values in individual stocks, and hard to be bullish on the U.S. stock market as a whole. It is a market that favors individual stock selection.

Meryl, do you agree with that?

Witmer: Scott is starting from the beginning of the year. I would start from Friday’s close. Based on that, I could see the market easily going up 5%, 6%, 7% for the year. Companies will have some cash accretion and pay down debt. As I’ve said, there is no great driving force in the economy. But valuations at the beginning of the year were brought down by a bad selloff in stocks. There are opportunities out there.

Schafer: We had a stealth bear market last year. Despite the fact that the averages didn’t do much, 70% of stocks in the Russell 2000 are down more than 20% from their 52-week highs. That is also true of 49% of the S&P 500, and 68% of the Nasdaq Composite. It really will be a stockpicker’s market, because a lot of stocks that are down 30% or 40% are buys now.

Zulauf: The median stock in the S&P 500 was down 22%. But stealth bear markets always turn into real bear markets. That’s how bear markets start.

Schafer: We are in a bear market now. But within that bear market, you can still buy good stocks. David Tepper [founder of Appaloosa Management] has a saying: There are times to make money, and times not to lose money. This is a time not to lose money.

Gundlach: I agree, and that’s not even a prediction. It’s an observation. The market’s breadth is terrible. Beyond that, the divergence in the performance of junk bonds and the S&P 500 was giving a monstrous sell signal when the Fed raised rates in December. You must pay attention to that sort of divergence. It happens maybe 10% of the time, and sends a signal that is never wrong.

Schafer: There have rarely been times in my career when there have been so many uncertainties, whether it’s interest rates or terrorism or China or the economy, or all the other things we have been discussing.

Gundlach: We started getting worried about geopolitical issues three or four months ago because of the lame-duck presidency and the time window leading to the next presidential election. It is the perfect time for bad actors, and, unfortunately, things are playing out as we feared.

Zulauf: In Europe, the rifts between the euro-philes and the anti-euro members are growing, as are the rifts between those who are for and against multicultural societies.

Gundlach: Felix, it seems to me [German Chancellor] Angela Merkel has been keeping the whole thing together. What happens if she loses her grip on power?

Zulauf: She has been a great moderator, but she has never taken a big stance on political issues. That is how she has remained in power for so long, riding a middle-of-the-road populist policy. Now the German people are becoming uneasy about the influx of refugees from the Middle East. Merkel could be in trouble. She has lost influence not just in Germany, but throughout Europe. She can’t fulfill the role of the moderator within Europe as she did in the past.

Priest: We look at three kinds of contagion: financial, economic, and political. Europe is the locus of political contagion. I agree with Felix: Merkel’s political popularity has slipped, but is still around 57%-58%. She has kind of lost touch with the people on the street, and the Cologne attacks [sexual assaults blamed on migrant gangs] aggravated that. Felix, what will happen to the Schengen agreement, which allows for free movement of labor across the European Union? If that ends, the whole euro structure will fall apart.

Zulauf: Schengen is dead. On the positive side, the EU could adjust its goals and become less centralist. That would keep things together. Alternately, if the bureaucrats in Brussels stiffen in its resolve to bring other nations into line, there is a risk the euro zone will break apart. The European economy surprised on the upside last year. At least it surprised me. Some major factors driving that growth are going to disappear. The euro won’t decline further against the dollar; the rate of change in oil prices will slow, and countries have loosened up on austerity. The European economy could soften this year.

Rogers: Every day, for 40 years, Thomas Rowe Price, the founder of my firm, said, Today is the most difficult day to invest.

Gabelli: He was right.

Rogers: Troubling stuff is always out there. As an asset allocator, I ask myself, Can you invest in a portfolio of businesses whose value will accrete by more than 3% a year? That is my expected bond yield, and the threshold for an equity investor.

Gabelli: It depends on your starting price.

Rogers: Correct. If earnings are up 4% this year and you add the S&P’s 2.2% dividend yield, you get about a 7% total return. I assume P/E multiples will be flat because I don’t really know. This suggests investors will have a tough year, but a decent one. Last year wasn’t all that bad. The S&P was up 1%, and the Nasdaq Composite, 6%.

Zulauf: The S&P rose because of a handful of companies with very rich valuations. I expect the bear market to continue, leading to opportunities to buy later in the year. We’ll probably have a better market in 2017. Let’s talk about it when the S&P reaches 1600.

Gabelli: I’m glad you said that before we ate lunch.

Priest: To me, stocks still are much more attractive than bonds, but your holding period has to be measured in years, not 12 months.

Nonetheless, where will the market end the year?

Priest: It will be flat to down slightly.

Cohen: My colleagues think S&P earnings could be pretty good this year, albeit not as high as the consensus estimate. We’re at $117, a gain of $10-$11 from 2015. Some of that growth reflects a pickup in energy-company earnings, and some, the absence of currency translation. Assuming the price/earnings multiple stays the same, my colleague David Kostin [Goldman Sachs’ U.S. equity strategist] has a year-end price target of 2100. But to summarize today’s discussion, you don’t buy the S&P. You are buying specific securities.

Rogers: Last year, in terms of fund flows, the S&P is all that anyone bought.

Cohen: I’m talking about the people at this table.

Gabelli: I’m in Meryl’s camp. From the day of this panel, stocks will rise and be flat for the year. Whether China moves quickly or slowly to devalue the yuan, currency translation will help my companies incrementally this year. Second, there will be some sort of surprise that lifts oil prices. In an election year, we will address issues like tax reform and corporate regulation. We’ll also have to address the issue of tax inversions. Heading into 2017, things will look OK.

Witmer: How should we address that issue? By lowering corporate taxes?

Gabelli: We’ll have to move from taxing company earnings globally to taxing them territorially [applying a 35% corporate tax rate only to income earned in the U.S.]. If that happens, the effective tax rate will be materially lower. No one is baking that into 2017 forecasts.

Gundlach: In equities, there has been a tremendous move toward passive investing. It is the opposite in fixed income. Index investing in fixed income was popular 20 years ago. When the Fed raised rates sharply in 1994, there was great turmoil in the bond market, and people doing wacky or creative things had horrible returns. Now we have moved into the world of uber-active management in fixed income, represented by unconstrained bond funds. Yet they have been a debacle. They are generating negative returns. It is interesting how the pendulum swings in this business. Do what you want, but just don’t tell me. Essentially, that’s what an unconstrained bond fund is.

The problem is, they end up turning into credit funds with relatively low interest-rate risk, which is exactly the wrong thing to own right now. Credit is doing poorly, and even with rates up last year, bonds delivered a positive return. I am worried about what might happen in the aftermath of the Third Avenue gating [Third Avenue Focused Credit fund barred shareholder redemptions last month as it moved to liquidate]. Here was an open-end 40-Act mutual fund that was supposed to allow redemptions daily. Then, without even telling the Securities and Exchange Commission, it froze investor assets. The fund said it was down 30% for the year, but that doesn’t seem correct. If you’re down 30%, sell your holdings and give the money back. It is possible the fund was down more.

Let’s say I’m invested in a similar fund, leveraged once. If the Third Avenue fund was down 50%, I’m wiped out. If I get a statement next month saying my fund was down 30% for the quarter, I’m going to say, “Get me out.” If I don’t get out first, I’ll be left with pay-in-kind energy bonds worth zero. I can see a redemption cycle occurring in credit hedge funds.

Gabelli: Where does this end?

Gundlach: We will see a higher default rate in the junk-bond market. Junk-bond issuance used to represent about 1% of GDP. Then it rose to 2%. It was something of a stimulant to the economy. Also, the stock market has been buyback-driven to an extent, and higher borrowing costs will make that more problematic.

Investment-grade bonds also have been dropping in value. The LQD [ iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF] consistently dropped in price through 2015. When interest rates rose, it was challenged by interest-rate risk. When the world looked problematic, it was challenged by credit risk. It seems like there is almost no way to win. When investment-grade credit is downgraded, it falls into junk territory, which makes it un-ownable for a large number of institutional investors. The credit market is sending a message, and the stock market, at least until recently, was whistling through the graveyard. When junk bonds fall 20% in price and the stock market sits at a high, something is wrong with the picture. These markets are moving like alligator jaws. Ultimately, they will move together.

In other words, you’re not too bullish on stocks.

Gundlach: If stocks stay where they are, junk bonds must go up. If junk bonds stay where they are, stocks must go down.

Cohen: But wasn’t the junk-bond market skewed toward industrial issues?

Gundlach: I am leery of arguments for taking out the bad stuff, which makes everything else look good. That’s just trying to sugarcoat the rot at the center. The credit market is clearly signaling a default cycle. Junk bonds have been weakening for 17-18 months. No wonder stocks had a bad start to the year.

You haven’t said much today about emerging markets. Felix, is your outlook dismal, or worse?

Zulauf: Emerging markets are satellites of China. Those in Northeast Asia are subcontractors, and those in Latin America are suppliers of commodities to Asia. Both are doing badly as China struggles. Brazil is in a virtual depression, and there are no signs of improvement. Economically, the business cycle is turning down. EM currencies began sliding ahead of China’s, and the decline isn’t over yet. Most are experiencing a balance-of-payments crisis. I would avoid emerging market currencies, bonds, and equities.

Gundlach: Emerging market equities are correlated to commodities prices. I can’t come up with a single good argument for owning emerging market equities versus U.S. stocks.

Cohen: One emerging economy that might move in the opposite direction in 2016 is India. The country has been moving forward with reforms. Structural issues are being addressed correctly, albeit slowly.

Gundlach: India is facing many potential positives that China faced a generation ago. Its labor force could see tremendous growth, whereas China’s labor-force growth will be zero. I have no idea what will happen to Indian stocks this year, but India is the thing to buy for your grandchildren’s education. Put your statements in a shoe box and don’t open it.

Cohen: We have talked today about the things investors might want to avoid in 2016. But from an asset-allocation perspective, where should you put your money? The dollar is an appreciating currency. It wouldn’t be surprising to see capital flow to the U.S. That could push P/Es higher than our models might otherwise suggest.

Priest: India has a major corruption problem.

Gundlach: There are all kinds of negatives. That means there is room for improvement.

Rogers: If people collectively feel there is no reason to invest in emerging markets, that could be reflected in their valuations. If Brazil is in a depression, perhaps that is when you want to buy.

Zulauf: Brazil hasn’t addressed its problems. It just fights the symptoms. As long as that is the case, the darkest hour hasn’t yet arrived.

Has Argentina turned the corner?

Zulauf: The new president and his team are excellent, but they have to restructure the economy. There will be layoffs and less welfare support for citizens, and the country will have to deal with foreign creditors. But, sometime this year, Argentina could become more attractive to investors.

Time for a quiz; we’ll grade you next year. Who is going to be the next president of the U.S.?

Black: Hillary Clinton.

Gundlach: Donald Trump.

Gabelli: Trump wins.

Cohen: One of the nominees will win. I expect them to be Hillary Clinton and Paul Ryan.

Priest: I agree with her on the nominees. Hillary Clinton is going to win.

Rogers: Chris Christie will be the Republican nominee and beat Hillary Clinton in a tight contest.

Schafer: Hillary Clinton will win.

Felix, you’re not a U.S. citizen, so you can’t vote. But you are permitted an opinion.

Zulauf: Hillary Clinton will probably make it despite her lack of integrity. Donald Trump would be good on a few points, but extremely dangerous for the world economy. He would close our doors to the world. Trump is a reflection of how upset the people are with the political establishment. You see the same development in Europe, which is bad news, because eventually it will put more populists in power. And that creates a much less stable world.

Witmer: I expect a Republican to win.

Gundlach: Hillary is going to lose badly. She is the opposite of what Felix discussed: the antiestablishment mood. The populist momentum is unstoppable. If Trump wins the nomination, he will own her in the debates.

Zulauf: Will the Republican Party allow a guy like Trump to run for the presidency?

Gundlach: He is running right now! The outcome of the election will be highly dependent on geopolitics and the economy, and neither is going to be supportive of the status quo.

Quiz over! Now, how are investors going to make money in what looks to be a devilish year? Brian, tell us where you see value.

Rogers: These are my criteria, particularly in the context of today’s discussion, where the most bullish commentary was that U.S. equities might rise by upper-single digits in 2016. That seems like a wide leap, based on where the market sits now. I have sought to identify a handful of companies with staying power, but with some controversy reflected in the share price. There aren’t many triple-A-rated companies anymore, but there are companies that have been through cycles and will last through other cycles. I look for management that is either strongly incentivized, under pressure, or feels some need to improve performance. Lastly, these companies present good valuation opportunities. Listed alphabetically, the first is American Express [AXP].

When I think of a blue-chip company, I think of American Express. It has a great legacy and innovative management, and develops great leaders. Also, the stock has been under tremendous pressure. Analysts rarely mention American Express without mentioning Costco Wholesale [COST], with which AmEx had an exclusive co-branded charge-card arrangement until last year. The separation takes effect March 31. The stock was a sloppy performer in 2015, and sold off to the point where we’ve got a low multiple on a historically high-return business.

How far did American Express fall?

It was down 25%, and closed Friday [Jan. 8] at $63.63. There are 985 million shares. Our earnings estimates are $5.30 a share for 2015, moving up to $5.50 this year. The dividend yield is 1.8%. The company raised its dividend last year, and probably will raise it again in 2016. It is giving guidance that earnings will be back to a 12% growth trajectory by 2017, which gets you to $6.35 a share next year.

Spending on leisure and business travel is up, and credit losses are down. Interestingly, the company has been hurt by lower prices for gasoline and airline tickets. But it doesn’t take a huge leap of faith to assume that if American Express maintains its P/E ratio, now about 13, and earnings come through in the next 18 months, you could be looking at an $82 stock. If you put a 10 multiple on earnings 18 months out, below today’s multiple, you have a $60 stock. So there is limited downside, decent upside, good management, and a board that is under a lot of pressure. There has been speculation that if the company’s fortunes don’t improve, there could be a management change. Management continues to buy back stock, and is shrinking the share count by about 5% annually.

Witmer: How is the balance sheet?

Rogers: The balance sheet is great, Meryl. Keep in mind, American Express is a bank now. Its dividend and buyback plans have to be approved each year by the Fed. The risks here are an uptick in credit losses, more adverse regulation than we’ve already seen, and a general economic slowdown. The stock went through its own bear market in 2015, which was unwarranted. By this time next year, people won’t be thinking about Costco.

Zulauf: What makes the loss of Costco such a big problem?

Rogers: The deal with Costco generated a mid-single-digit percentage of American Express’ revenue. They lost the contract.

Gundlach: Mid-single digits came from that, and the stock is down 25%? That’s out of line.

Rogers: That’s what we think.

Zulauf: The AmEx card isn’t as widely accepted by merchants as other cards, because American Express charges merchants a higher fee.

Black: That is more of an issue in Europe than the U.S.

Gabelli: This has been an issue since forever. But the number of cards in force keeps going up.

Rogers: Moving on, Comcast [CMCSA] is the only stock I’ll mention that didn’t have a bear-market decline last year. It was down 2.7%. The business is two-thirds cable TV and one-third NBC Universal. If the hurdle is a bond yield of 3%, Comcast’s value will accrete by more than 3% in almost any given year. Comcast could earn $3.70 a share in 2016, probably going up to $4.15 in 2017. There are 2.5 billion shares. Chairman Brian Roberts and his family control about 33% of the stock.

There was a lot of excitement around the stock last year when the company attempted to acquire Time Warner Cable [TWC]. The deal fell apart in April, and Comcast then turned its attention to accelerating share repurchases. It bought back about 3% of its capitalization in 2015 and will continue to buy back shares in 2016. We look at Comcast as an asset-rich company, whether it’s the Universal theme parks, the Philadelphia Flyers, or the value of NBC. We try to apply a P/E multiple or a multiple of enterprise value to Ebitda [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization], or a price-to-free-cash-flow multiple to these assets. In doing so, we come up with a stock price of $69, versus Friday’s close of $54.67. Using bearish assumptions, we get a stock price of $50; putting in bullish assumptions, we get a price of $78. Some other folks have done valuation work based on multiples of cable and NBCU Ebitda, and come up with a price of $80. There is no China risk here, and less economic cyclicality risk than in some other companies.

But there have been widespread concerns about cable-TV subscribers canceling service or “cutting the cord.”

Rogers: Subscriber growth has been holding. Comcast has introduced a fancy X1 interactive product, and will continue to roll out X1 products in the next couple of years. After 2017, cash flow will improve as the company will be making less of an investment in the X1.

Comcast management made good decisions last year. The Time Warner Cable decision was made for them by regulators, but buying back stock was probably at least as good as an investment as TWC would have been.

Witmer: Doesn’t Comcast make most of its money from providing broadband Internet service?

Gabelli: Yes. The video part of cable has become a marginal contributor.

Rogers: We talked today about the lack of momentum in industrial America. That brings me to Eaton [ETN], which closed Friday at $49.17. The company makes electrical, hydraulic, automotive, and aerospace products. Eaton bought Cooper Industries in 2012. It was a really good deal.

Eaton’s stock was down 23% in 2015, after falling 11% in 2014. The company has a $23 billion market value. It has good businesses, but a challenged earnings outlook has caused the stock to weaken. Eaton could probably earn $4.25 for 2015 and $4.30 in 2016, so I’m bullish on about five cents. Management raised the dividend to $2.20 a share last year. The stock yields 4.4%, and the payout ratio is almost 50%. They could take the dividend up to $2.40 this spring, for a yield of nearly 5%. The company was profitable even in the last downturn, in 2008 and 2009, when other industrial companies were challenged. Eaton has peak earnings power of somewhere in the $6-$7 range. It bought back 2% of its shares last year, and will buy back stock this year. It is cutting costs aggressively.

What is the company worth?

If you put multiples that aren’t particularly high on the electrical, hydraulics, aerospace, and vehicle businesses, and subtract debt, you get a hypothetical stock price in the $65-$75 range. The CEO, Sandy Cutler, who has been running the company for a long time, will retire in the spring, and Craig Arnold, another Eaton veteran, will succeed him. Eaton is a good business, with strong financials, cyclical head winds, and decent profitability. The stock has significant upside if and when the economic environment improves.

Schafer: Will there be any change with the new management?

Rogers: I don’t expect so. Cutler has been a good leader. Some people might say the company could have used a breath of fresh air, and should have hired an outsider to replace him. But Arnold has been there for years, and will do a fine job. It’s steady as she goes.

Black: Eaton has no revenue growth. There is no inflection point that I can see in the next three to six months.

Rogers: That’s why the stock is down 30%. It’s anyone’s guess when Eaton will return to peak earnings power.

Gabelli: They’ve got great businesses that they are running well.

Rogers: And I am convinced the dividend yield is safe. This is like a bond with a call option.

Witmer: Why would they pay out so much in dividends?

Rogers: They generate a lot of cash flow and don’t have many things to invest in.

Schafer: You’d rather they spend the money on dividends than a dumb acquisition, which many other companies do.

Rogers: Absolutely. My next recommendation is my most controversial. Macy’s has been in the news a lot more than it might have wished. The company announced recently that it was taking earnings guidance down. On the day it announced, the stock went up a bit, which I consider a good sign. Macy’s operates 770 Macy’s stores, 50 Bloomingdale’s, and Bloomingdale’s outlets. The company has a $12 billion market cap and annual revenue of $27 billion. Management reduced its earnings outlook for the year ending this month to $3.85 a share. The stock closed last Friday at $35.89.

Forecasting earnings here is tricky, as Wall Street expected Macy’s to earn $4.25 a share for the year. A bold guess for the fiscal year ending in January 2017 would be that earnings are flat, although that could prove optimistic. Macy’s raised its dividend last year to $1.44 a share, giving the stock a 4% yield at today’s price. The stock is inexpensive at 9.3 times earnings, and 5.5 times enterprise value to Ebitda. Macy’s has been making progress on its Internet businesses, both at macys.com and bloomingdales.com. But it had more competition from other online retailers in the fourth quarter, and suffered from bad weather.

Cohen: You mean good weather. They weren’t selling enough coats.

Rogers: Warm weather in the winter is bad for Macy’s. Likewise, a strong dollar reduced tourist traffic at the stores. These things are reversible, and management responded by saying it would close some stores and cut costs. The company has cut its capitalization faster than its store count. Share count has been reduced to 330 million shares from 540 million 10 years ago.

Starboard Value, an activist investor, has been involved with Macy’s, and claims the company’s assets are worth $21 billion. Relative to its market value, that is a big gap. The company has been invigorated by this investor and is examining different possibilities for change. At nine times earnings, and with a 4% yield and potential changes in how the company is run, this seems like an intriguing situation.

Could the changes involve new management?

Gabelli: No. Terry Lundgren [Macy’s CEO] has done a great job.

Black: Brian, are you buying this on earnings power or potential monetization of the real estate assets?

Rogers: I am buying it because there is a lot more value in Macy’s than the $12 billion market cap reflects. Lundgren has done an excellent job, and the chief financial officer is outstanding. They know the pressure they’re under, and are trying to do the right thing.

Occidental Petroleum [OXY] is a large independent oil producer. It has a market value of about $48 billion, and is the largest producer in the Permian basin. The CEO, Stephen Chazen, is stepping down this spring, and Vicki Hollub, who has been with the company for several decades, will succeed him. Occidental was once viewed as the low-quality company in the sector. Management has done a great job of selling assets, monetizing assets, and investing in the right sectors. The company is financially strong, with a single-A credit rating.

We’ll see what happens if oil falls further.

Rogers: Estimating the value of Occidental is tricky. In 2013, the company generated Ebitda of $14 billion. In 2015, it will be $5 billion. Earnings have been similarly volatile. A few years ago, the stock was trading above $100 a share and the company earned eight bucks. For 2015, it could earn all of 28 cents. You don’t buy a company like Occidental based on its current earning power. The dividend was increased last year to $3 a share; the stock yields 4.7%.

Is the dividend safe?

Rogers: In its most recent investor presentation, Occidental talked about growing the dividend on six out of eight pages. When a company does that, I am willing to bet the dividend is safe for at least two or three years. They can certainly cover it out of operating cash flow.

Do you feel the same about the dividends of most of the oil majors?

Rogers: The majors can maintain their dividends for a few years. It isn’t a foregone conclusion that they can maintain them forever, no matter what happens to oil prices. In Occidental’s case, the company is cutting capex from $9 billion in 2014 to $4 billion this year. Chevron [CVX] is also cutting capex and using the money to help fund the dividend. This isn’t a good long-term strategy, but in the short term, it is defensible.

Zulauf: If more companies cut capital spending dramatically, that would be bad for GDP this year.

Rogers: You aren’t going to have growth coming from the energy sector, that’s for sure.

Priest: Few oil companies can maintain their dividend at current levels if oil stays at $30 a barrel. Dividend payments can be sustained by capex cutbacks for a while, but that is scary. Depending on how much leverage a company has, a weird thing could unfold, whereby the present value of the asset side of the balance sheet is collapsing, while nothing is changing on the other side. There is an insolvency problem brewing in that whole industry. We happen to own Oxy, but the whole environment is volatile.

Rogers: Occidental has production growth and will be a survivor. If dividend cuts are coming, Oxy won’t be in the first wave. It is an intriguing situation if you are a true contrarian.

Lastly, we like Qualcomm [QCOM]. This is a cash-flow-return-to-shareholders story. Qualcomm makes chips for smartphones and licenses intellectual property to almost every smartphone manufacturer. The company has disappointed shareholders for the past few years. The stock lost 32% last year.

Qualcomm has $70 billion in market value and $10 a share of net cash. The stock closed Friday at $45.88. In the year ended in September 2015, Qualcomm earned $4.60 a share. They will probably earn $4.90 in the September 2016 year.

What is the dividend?

Rogers: They pay $1.92 a share, and the stock yields 4.2%. The former CEO, Paul Jacobs, became executive chairman a few years ago, and Steven Mollenkopf was promoted to CEO. Steve is focused on shareholder value, and stock buybacks and dividend growth have picked up. We think the licensing business is worth between $40 and $43 a share, based on a 20-year discounted cash-flow analysis, and the chip-making business is worth $16 a share, based on a multiple of 12 times earnings. The two businesses, plus the net $10 a share of cash—we only count the accessible cash that isn’t overseas—gets you to a $69 stock price.

There are many risks here, and opportunities. Jana Partners became involved last year as an activist investor, arguing for the company to be broken into two separate businesses. Qualcomm opted not to do that. The company has had a lot of licensing disputes with Asian governments. When we add up the cash flow from licensing and the earnings from chip-making, the stock is selling at too big of a discount to underlying value. This is an interesting situation for an income-oriented investor.

Last year, a lot of the action was in the FANG stocks— Facebook [FB], Amazon, Netflix [NFLX], and Google [GOOGL], now called Alphabet . Many good companies were down between 10% and 30%, not just in the oil patch. I look for out-of-favor companies with good dividend yields and long-term staying power.

Thanks you, Brian. Oscar, you’re on.

Schafer: I have three stocks, all down about 30%. The first is Evertec [EVTC], the dominant transaction-processing company in Puerto Rico. It processes 75% of all merchant transactions, and more than 70% of all ATM and debit-card transactions. It also provides bank-processing services, predominantly for Banco Popular, which is owned by Popular [BPOP], Evertec’s former parent. It was carved out of the bank in 2010.

Evertec is expanding across Central and South America, to countries such as Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru, and the Dominican Republic. Revenues are recurring, returns on capital are high, and the business generates a lot of free cash flow, which it regularly returns to shareholders. Despite these attributes, the stock sells for less than 10 times earnings, while similar businesses in the U.S., Europe, and South America all fetch 20 to 25 times earnings.

Why the steep discount?

Schafer: The knock on Evertec is its location. Puerto Rico accounts for more than 80% of its business. It is burdened with an overwhelming level of government debt, a high unemployment rate, and a shrinking population. Its economy has been in a recession for nearly a decade. I can’t tell you when the Puerto Rican debt crisis will be resolved, but it sounds like a restructuring might finally take place. Anything that improves the economy would help make Evertec a home run, but we don’t need an improvement in Puerto Rico for the stock to do well.

Why is that?

Evertec is benefiting from a secular shift from cash transactions to electronic payments. This transition is still is in the early innings. Only 50% of the population of Puerto Rico is banked, versus more than 75% in the U.S., and card-usage levels are relatively low. Last year, Evertec’s board hired a new CEO, Morgan Schuessler, tasked with managing the business in Puerto Rico and re-accelerating the growth in other countries. He is well suited for the job, as he executed a similar playbook at Global Payments [GPN]. He has already announced a key win with the second-largest bank in Puerto Rico, and the company’s first acquisition in Colombia.

If new management can accelerate growth, Evertec could trade in line with U.S. peers, or for double the current price of $15. Eventually, it could be attractive to large, global payment companies for its regional footprint and favorable tax rate. A few weeks ago, Global Payments agreed to acquire Heartland Payment Systems [HPY] for 30 times earnings.

What is Evertec’s market capitalization?

Schafer: It is $1.2 billion. Calpine’s shares, like Evertec’s, have fallen to $14 from $23. Calpine has a $5 billion market cap. It is an independent power-producer generating 27,000 megawatts of power from natural-gas-fired and geothermal plants in California, Texas, and the Northeast. As a wholesale power company, it sells into competitive markets. As a result, it doesn’t earn the steady, guaranteed returns of a typical regulated utility. It is a tough business, and I often view the industry as a cautionary tale about deregulation, overbuilding, and bankruptcy.

Calpine took a spin through bankruptcy court.

Schafer: It filed for bankruptcy protection in 2005. At the time, it had the dubious distinction of being the eighth-largest bankruptcy in U.S. history. To steal a line from my friend Howard Marks [co-founder of Oaktree Capital Management], there aren’t any bad asset classes, just bad prices. In the case of Calpine, the stock is too cheap to ignore. Calpine is trading for only five to six times our estimate of 2017 free cash flow per share, and at less than half of replacement value. The management team is uniquely focused on creating value for shareholders.

When your readers are finished with this week’s Barron’s, I would encourage them to read the first few pages of Calpine’s 10K, where management lays out its investment philosophy.

You mean if, not when.

The stock is down for two reasons. Mild weather has led to low power prices, and investors are worried about the long-term impact of competition from renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind. I can’t predict the weather, and I expect renewables to continue to grow and disrupt the power and utility industries, which is a wonderful thing. But for the foreseeable future, most energy will be from the least environmental, least flexible, and most expensive sources, mainly coal-fired and nuclear generation. I expect Calpine to continue generating strong cash flow, which management will allocate in intelligent ways. The shares could double in the next one to two years.

Does the company have much debt today?

Schafer: It is levered five times to Ebitda.

Will management use any of the free cash flow to pay down debt?

Schafer: It depends on the stock price.

I love to seek out management teams with which I have had success in the past. I particularly like investing with a team that confronted a similar fact pattern that led to significant gains in a prior period. That is the case now with CommScope Holding [COMM]. The company is a leading provider of cell-tower antennas for wireless carriers, and provides fiber solutions for residential networks and data centers. The business has grown by 3% or 4% a year, and should continue to benefit from increasing demand for bandwidth.

CommScope’s business can be lumpy, quarter to quarter, or even year to year, as its largest customers are the major telecoms around the world. This lumpiness has hurt the stock. Nonetheless, management has done an excellent job of improving profit margins. In the past 10 years, operating margins doubled to 20%.

In August, CommScope closed its third major acquisition. Having watched this management excel at integrating and optimizing prior acquisitions—Avaya Connectivity in 2004 and Andrew in 2007—I am confident that there is significant opportunity for earnings accretion in the next three years as the company integrates its newest purchase, the telecom, enterprise, and wireless business of TE Connectivity [TEL]. Based on the stock’s valuation, many others don’t agree.

What is the stock price?

Schafer: CommScope is selling for $23.36, or 10.5 times analysts’ 2016 earnings estimates and 8.5 times 2017 estimates. The company is levered at 4.6 times trailing Ebitda, but given the strong secular tail winds, I am not as concerned as I might be with a cyclical industrial company. The stock has at least 50% upside, and closer to 75% in the next 18 months.

Last year, I recommended NICE-Systems [NICE], an enterprise-software company. The stock has risen 10% since then, but there could be 40% upside from here. New management has an opportunity to create significant value for shareholders by optimizing the company’s bloated expense structure and overcapitalized balance sheet. In the past year, NICE expanded its profit margins, sold two noncore businesses, and generated a lot of free cash flow. The stock is selling for $55, and the company has $14 a share of net cash. It will probably earn $3.50 a share this year, so it is cheap at 12 times earnings, excluding the cash. NICE has a growing revenue stream and continued optionality around business-model enhancement and cash deployment.

That’s pretty nice. Thank you, Oscar.