Let’s tie two topics we have treated, one in exhaustive depth and the other in an ongoing series. They are bitcoin and capital consumption. By now, everyone knows that the price of bitcoin crashed. Barrels of electrons are being spilled discussing and debating why, and if/when the price will go back to what it oughtto be ($1,000,000 we are told).

As an aside, in what other market is there a sense of entitlement of what the price ought to be, and a sense of anger at the only conceivable cause for why the price is not what it ought?

Bitcoin, Postmodern Money

Anyways, during the incredible run up in price, we wrote a series of articles, entitled Bitcoin, Postmodern Money. We were not focused on the price of the thing, other than to discuss the problems of unstable price, and even rising price. We did not say the price will come down, or when. We said a rising price makes it unusable as money.

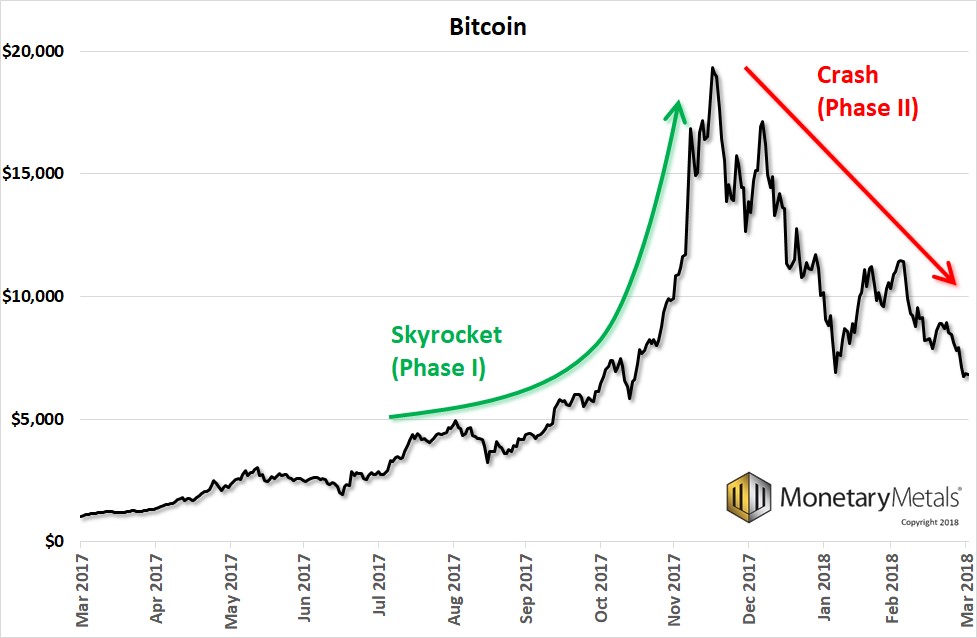

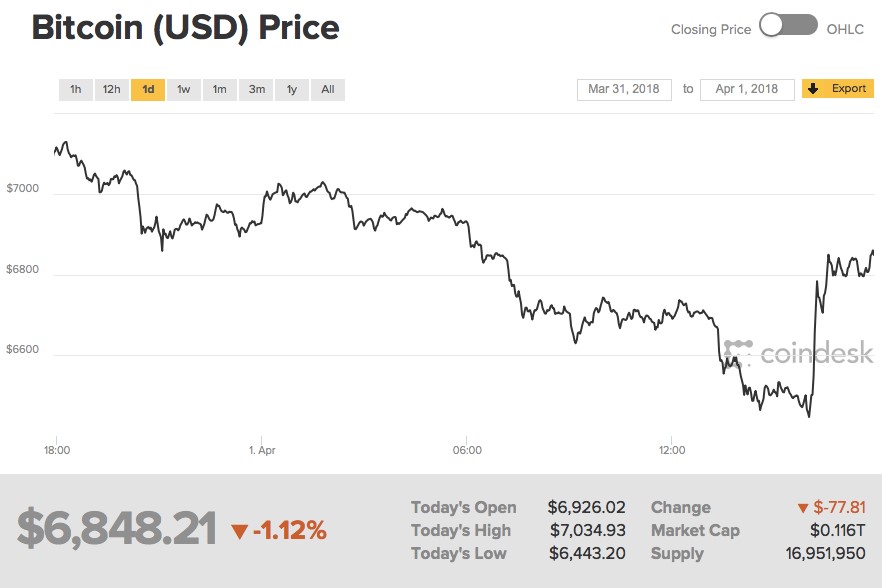

In an online forum, some folks insisted that bitcoin is a store of value (in contrast to the dollar). We said that even if you don’t think it will crash, a skyrocket is not a store. Here is the graph through Friday.

Obviously, the skyrocket is just Phase I. There is another phase afterwards. Will there be another skyrocket phase? Will it get higher than the last peak around $20,000? We don’t know, and obviously those who were calling for $1,000,000 when it hit $20,000 don’t know either—gold and silver is not the only market in which fools promote higher prices to credulous audiences. Our point is something else.

When the price crashes, as it has from $20,000 to $7,000—a loss of 65 percent by the way—everyone knows that dreadful losses have been incurred. It’s just that most people think the losses occurred when the price went down. If you take this idea to its logical conclusion, you’d have the central banking thesis in a nutshell: just prevent price from going down!

We disagree. The losses actually occurred on the way up.

Back in December, when you gave your $20,000 to someone to buy his bitcoin, that is where your capital was consumed. Let’s drill down in this.

The seller bought 15 bitcoin years ago, when they were selling for $50. So he forked over $750 to someone who had bought them previously. That guy took his profits, and ran all the way to the wireless store to buy the latest smart phone. His profit was the buyer’s capital. But it was only $750 so who noticed. Chump change.

But that buyer waited for the right moment (as we know in retrospect). He sold at $20,000. You bought one, and 14 more, for a total of 15. His total proceeds are $300,000. Even if he subtracts his original capital of $750, he still has a profit of $299,250. He ran to the Ferrari dealer.

To buy the Ferrari, he spends your capital. It was converted to an automobile. This, right here, is where the loss was incurred. Your capital is no more, and instead there is a consumer good which is happily being consumed by the bitcoin seller. At the end of 100,000 miles, the car will be all used up. Your capital will all be used up.

Suppose bitcoin had gone on to $120,000 and you sold out then. In that case, your capital was still consumed by the Ferrari guy. The difference is that someone else gave you $1,800,000 of his capital. So you feel whole. Not only whole, but you feel like you have made a profit. You can buy not just a Ferrari, but a yacht too.

And suppose the price went on from $120,000 to $240,000. And then to $520,000. And then to $1,000,000 and beyond. Nothing fundamental changes, only the number of participants in the scheme, and the total amount of capital converted to consumer goods.

We spell it out this way to illustrate that this process is both destructive and unsustainable. There is only so much capital to be consumed, and once all of it is (or all of it that people are willing to fork over to be consumed) is gone, then the skyrocket phase ends. It must, necessarily, end.

The skyrocket phase is unsustainable.

We have said all of the above already in part and in whole, and in several different ways. We have a new point to make, and we believe it is a very important one.

Defining Investment

There is something wrong with defining an investment to be when you hand off your capital to someone and wait for someone else to hand over more of his capital. This is his wealth accumulated over a lifetime of hard work, or his family estate accumulated over centuries. It is coming to you as a gain on your speculation, to be consumed as you will. This is nothing more than a conversion of one man’s wealth into another’s income.

It is unsustainable.

If you define investment this way, you are arguing that an important process of capitalism—arguably the key process—is unsustainable. You are saying that investment enriches the investor while impoverishing everyone else, via a process of consumption of capital. Or at least that capitalism includes such a destructive process.

This gives fuel to moralizers and power-lusters everywhere. It supports their feeling that capitalism is destructive, and that it’s socialism which properly stewards capital. But that is the exact opposite of the truth. Socialism is the system of capital destruction.

The truth is that in capitalism, there is not an ongoing process of wealth destruction. Sure, in a free market, people are free to bid up the price of anything as much as they want. However, there are no perverse incentives to push them to do so.

Investment is the financing of productive activity. The profit to the investor comes from the new production enabled by the investment. This is not only sustainable, but it enriches everyone. The investor makes a return on his investment, the entrepreneur makes a profit, his employees earn wages, and everyone else has access to more and better goods and services. Investment is win-win.

Speculation is win-lose. The losses occur during the skyrocket phase but are only realized during the crash phase.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

This Report is issued on Tuesday, as yesterday was Easter Monday and a holiday in many parts of the world. Incidentally, Easter is approximately the time of year when the sun has moved to the midway point from its southerly and northerly extremes, as it revolves around Earth in its precessing orbit.

In the 11 times that the sun has revolved in its orbit around the Earth since our last Report, the yellow commodity went down $22 dollars, and the more-volatile white metal went down in money terms 22 cents.

By the time you are reading this, Las Vegas will have moved to Keith while Arizona moves away…

We all know that the sun does not revolved around Earth, and that travel does not mean that places on Earth move towards or away from you. The sun is the reference point for the Earth, and landmarks on Earth are the reference point for travel. Yet most still insist that the dollar is the reference point for gold. Though everyone knows that the dollar does down over long periods of time, thus there’s lots of discussion of 1990 vs 2000 vs 2018 dollars.

While most agree that gold must be measured in dollars, they measure the dollar in consumer prices. Or in euros, which are measured in consumer prices.

It’s enough to vex a monetary scientist!

Anyways, one thing is for sure. Gold becomes more abundant to the market at times, and scarcer at others. So let’s take a look at the only true picture of the supply and demand fundamentals for the metals, in light of the changes in their prices this week. But first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

(Click to enlarge)

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). The ratio fell fractionally.

(Click to enlarge)

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

(Click to enlarge)

Look at that. The dollar goes up a bit (as reckoned objective, i.e. in gold, which is the inverse of reckoning gold in dollar terms, and saying that gold fell). And so does our measure of scarcity (i.e the cobasis, the red line).

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price rose $9 this week, to $1,449. Now let’s look at silver.

(Click to enlarge)

In silver, we see a nice little backwardation. That is, one could make a profit by decarrying silver. For the May contract, the return is close to 1 percent (annualized). Compare to the June gold contract, which is farther out, whose cobasis is below -1 percent. It’s not just the price of silver which is more volatile, so is its basis.

The basis of the near contract is especially volatile in silver, with its tendency to head for the moon (proving that banks are not naked short). Compare the near-expiry May silver cobasis to the Silver Basis Continuous (basis around +2 percent, cobasis around -2 percent).