“Make in India” has failed to meet its objective of turning industry around. The government has seemed more concerned with improving India’s rank in the spurious Ease of Doing Business Index, which anyway did not result in higher investment.

1 Introduction

For over two decades now, the share of the manufacturing sector in India’s GDP has stagnated at around 14%-15%; that of the larger industrial sector (which includes mining, manufacturing, power and construction) has also stagnated at around 26%-27%.

India has been showing a growing import dependence in most industries, especially in the all-important capital goods or machinery sector (Chaudhuri 2013). This is reflected in rising royalty payments and license fees to foreign companies for industrial technologies (Mani 2018). The ominous signs were, however, ignored during India’s economic boom of 2003-08. There was a wishful belief that India’s trajectory would be as a software superpower (the world’s back office) specialising in higher value-added services. India was at the time the world’s fastest growing large economy, nipping at China’s heels.

The 2008 global financial crisis, the Great Recession, and China’s rising technological prowess put paid to India’s ambition of becoming a superpower. In response, the National Manufacturing Policy was mooted in 2011 to increase the sector’s share in GDP to at least 25% by 2022, and to create 100 million additional manufacturing sector jobs. The idea was recast in 2014 as the “Make in India” initiative with the following objectives:

- Target of an increase in manufacturing sector growth to 12-14% per annum over the medium term.

- An increase in the share of manufacturing in the country’s Gross Domestic Product from 16% to 25% by 2022.

- To create 100 million additional jobs by 2022 in [the] manufacturing sector.

Nearly five years later, what has Make in India achieved?

[W]hile the EDB rank has improved the Make in India campaign has not succeeded in increasing the size of the manufacturing sector.

The unstated premise of Make in India was that manufacturing can be made to grow only if business enterprises are freed from burdensome regulations. The argument is that investment and production are held back because business is shackled by excessive rules and procedures—such as the time taken to get permissions and the laws protecting formal sector workers. Towards this end and to showcase its deregulatory efforts, the government chose to improve India’s rank in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business (EDB) index, believing that a higher rank would translate into higher industrial investment and output growth. Hence, in official pronouncements, an improvement in the EDB rank was shown as emblematic of the success of the Make in India campaign. However, as we shall see, while the EDB rank has improved, the Make in India campaign has not succeeded in increasing the size of the manufacturing sector relative to domestic output.

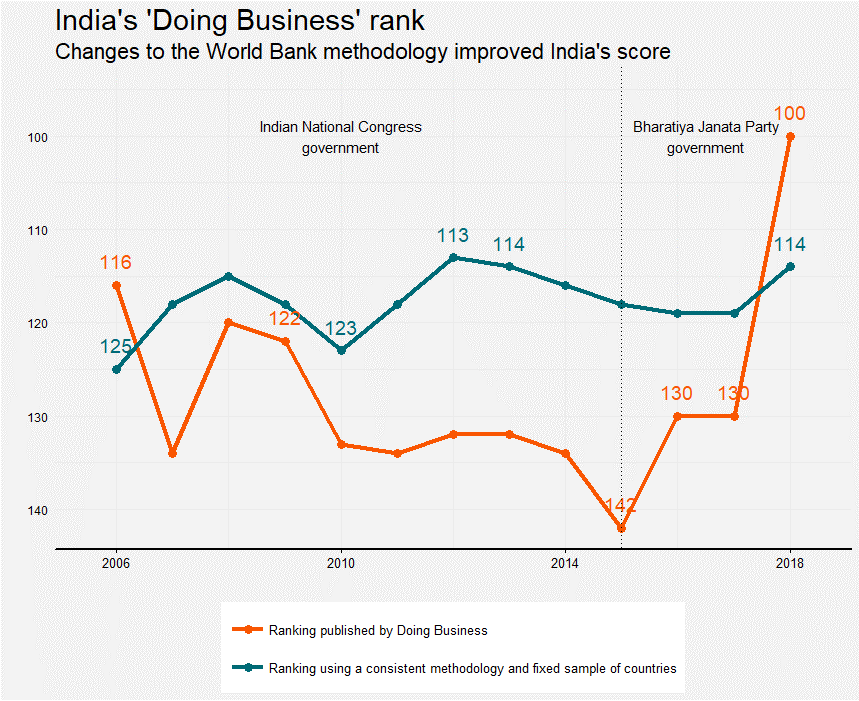

India did well in upping its EDB rank from 142 in 2014 to 77 in 2018. Enthused by the success, the Prime Minister at the Vibrant Gujarat Summit in January 2019 said:

“From 142 in 2014 to 77 now, but we are still not satisfied. I have asked my team to work harder so that India is in the top 50 next year. I want our regulations and processes to compare with the best in the world. We have also made Doing Business cheaper” (The Hindu, January 18, 2019).

But the improvement in the EDB rank has failed to revive industry. Why? This is the puzzle that we hope to understand here.

2 Evidence on Industrial Performance

The share of manufacturing and the industrial sector in GDP are useful aggregative measures of industrialisation. Figure 1 reports the ratios for India for selected years.

Source: National Accounts Statistics, various issues

For both manufacturing and industry a word about the data. As is now well-known there have been many and in some cases inexplicable changes in the methodology and databases. The data for the years 1990-91 to 2012-13 are based on the earlier (base year 2004-05) National Accounts Statistics (NAS); the data for 2012-13 and 2017-18 are based on the new NAS series (base year 2011-12). As many changes were brought about in its methodology and the databases used, the ratios are distinctly higher in the new series, compared to the earlier one.1

Regardless of the series used, the stagnation in the manufacturing and industry-GDP ratios is pretty evident as the ratios have barely moved up. Or to put it starkly, the Make in India initiative has made little progress during the last five years.

Source: RBI Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy

Make in India has little to show for its success in terms of output and investment growth—and a far cry from its ambitious targets.

There are three sources of national data for measuring industrial output, namely, (i) the Index of Industrial Production (IIP), (ii) the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) and (iii) the NAS. The average of annual growth rates for the period 2013-14 to 2016-17 varies widely among them; from 3.8% in the IIP, to 8.4% in the NAS, with the ASI recording a growth rate of 5.9%.2 While the merits of each of the alternative industrial growth estimates are known and have been widely debated, what is perhaps important to note is that they are nowhere near close to meeting the Make in India targets of a 12-14% annual growth in manufacturing and 25% share in GDP.

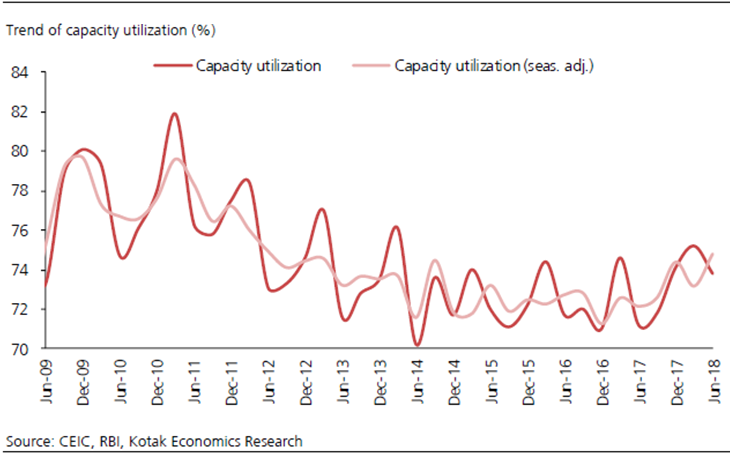

Figure 3: Industrial Capacity Utilisation

According to the ASI, the annual growth in real fixed investment in manufacturing averaged over the three years since 2014-15 is a mere 1.5%, and employment growth is 3.7%.3 A poor industrial performance is also corroborated by related variables such as bank credit and capacity utilisation, which have decelerated over a longer period (Figures 2 and 3). These trends are also consistent with the declining aggregate (economy-wide) fixed investment and domestic saving, as proportions of GDP (Figure 4). In short, Make in India has little to show for its success in terms of output and investment growth—and a far cry from its ambitious targets.4

3 On the Rising Ease of Doing Business Index Rank

The EDB index of the World Bank, by examining the formal legal and administrative procedures required to be followed by firms for both starting and running a business, seeks among other things to measure the time taken to comply with various regulations. It then ranks the countries accordingly. The underlying assumption is that firms in developing countries suffer from excessive state regulation in various areas (including the need to protect formal sector workers) that throttles the formation of new enterprises and disturbs the running of businesses—all adversely affecting output growth from the supply-side. Often cited examples are New Zealand and Singapore, which compete for the top slot in the index, where it apparently takes less than a day’s effort to start a new business enterprise, whereas in India it is said to take, on average, 130 days.5

[T]he government of India’s single-minded pursuit to improve the EDB index rank was a futile effort to signal a reduction in the regulatory burden and enhance private investment to achieve Make in India goals.

An important premise of the EDB index is that the poor in developing countries suffer from a lack of property rights, and that this delays their ability to start businesses. This is inspired by the perspectives of De Soto (1989) and Shleifer and Vishny (1998), who came to wield considerable influence on the perspectives of international organisations.

The EDB index consists of 10 sub-indicators under various heads, such as starting a business, labour regulation, customs regulations, etc. For all the indicators, less government intervention is deemed to be better for business (with the underlying principle being that the free market is the best governing principle). EDB is a de jure, not de facto measure of the time taken for obtaining various permissions. These estimates are based on information obtained mostly from corporate lawyers, with the surveys conducted by private consultants in select large cities (only in Mumbai and Delhi in India, for instance).

Source: National Accounts Statistics, Various Issues

However, there is a growing body of literature critical of the EDB index. The World Bank’s own internal watchdog, the Independent Evaluation Group, has prominently questioned the reliability and objectivity of the index (World Bank, 2013). Comparing the World Bank’s EDB index with its own firm-level Enterprise Surveys, Hallward-Driemeier and Pritchett (2015) said,

Overall, we find that the single numerical estimate of legally required time for firms to complete certain legal and regulatory processes provided by the Doing Business survey does not summarize even modestly well the experience of firms as reported by the Enterprise Surveys. (p 123)

More seriously, a World Bank research report has shown that there is no relationship between the changes in EDB ranking of developing countries and the inflows of foreign direct investment. To quote:

The World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business reports have been ranking countries since 2006. However, do improvements in rankings generate greater foreign direct investment inflows?...The paper shows this relationship is significant for the average country. However, when the sample is restricted to developing countries, the results suggest an improved ranking has, on average, an insignificant (albeit positive) influence on foreign direct investment inflows...Finally, the paper demonstrates that, on average, countries that undertake large-scale reforms relative to other countries do not necessarily attract greater foreign direct investment inflows. This analysis may have important ramifications for developing country governments wanting to improve their Doing Business Rankings in the hope of attracting foreign direct investment inflows. (Jayasuriya 2011: Abstract; emphasis added)

Figure 5: India’s Doing Business Rank

Source: Sandefur and Wadhwa 2018a (accessed on February 13, 2019)

Further, the meaninglessness of the index in terms of promoting foreign investment can be illustrated with two telling examples. Russia, like India now, improved its EDB rank from 120 in 2012 to 20 six years later, taking it ahead of China, Brazil, and India—but without seeing an improvement in investment inflows. China, on the contrary, attracted one of the highest capital inflows but its EDB ranking was low and hovered between 78 and 96 for the years between 2006 and 2017.

Note: As many private equity funds have liquidated their investments in Indian firms recently, in our view, net FDI inflow as a more appropriate measure of investment. Source: RBI Hand Book of Statistics on Indian Economy, and DIPP data on FDI inflow.

Source: RBI Hand Book of Statistics on Indian Economy, and National Accounts Statistics, Various Issues.

Similarly, India’s rank from 2006 onwards was between 124 and 140, but in 2017 it jumped to 100, apparently on account of a few changes in the EDB’s methodology. However, if the older methodology is followed consistently, the improvement in the rank simply vanishes! (Sandefur and Wadhwa 2018a) (Figure 5). This only demonstrates the fragility of the underlying methodology. Further, for India, the evidence on the association between an improvement in the EDB index and the fixed investment rate; and between the EDB ranking and FDI inflows is very limited (Figures 6.1 and 6.2).6

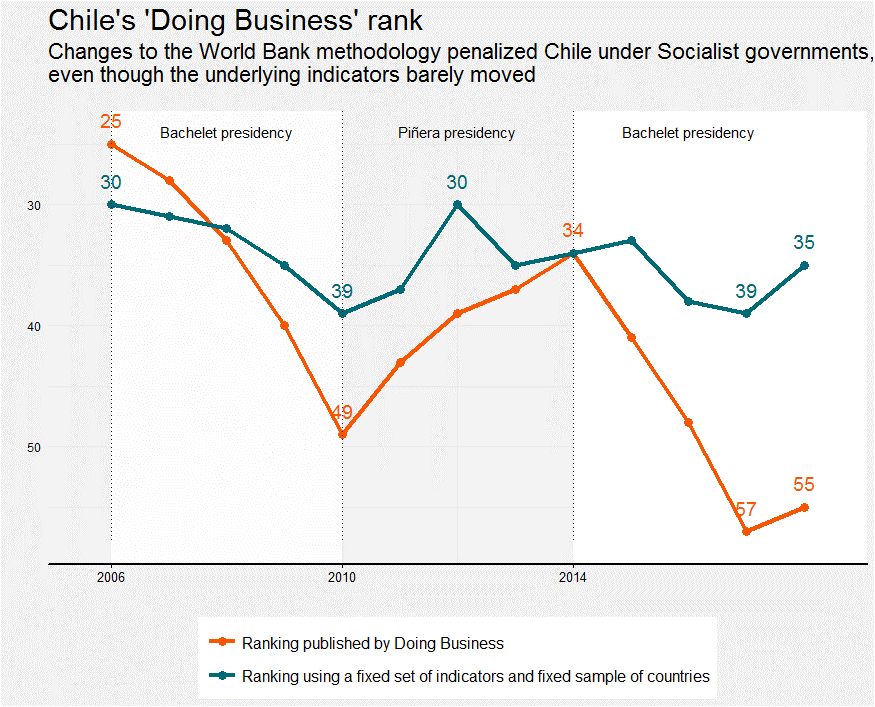

Figure 7

Source: Sandefur and Wadhwa (2018a) (accessed on February 13, 2019).

More seriously, a recent episode exposed the ideological bias of the EDB ranking. Last year, Chile’s former President, Micheal Bachelet complained that the EDB rank for the country systematically deteriorated during her socialist presidency, while it improved during the presidency of the conservatives. On a closer perusal, it was shown that Chile’s rank did not change much over the years under the older, unchanged methodology (Figure 7). Hence it was argued that the World Bank was interfering with the methodology underlying the EDB ranking to show Chile’s socialist regime in a poor light (New York Times 2018); an accusation endorsed by Paul Romer then Chief Economist of the World Bank, and last year’s Economics Nobel laureate (Sandefur and Wadhwa (2018b).

In the light of the above, it is fair to infer that the EDB ranking is a spurious index. Therefore, the government of India’s single-minded pursuit to improve the EDB index rank was a futile effort to signal a reduction in the regulatory burden and enhance private investment to achieve Make in India goals.

4 An Illustration of the Ease of Doing Business Measure

If the EDB index’s analytical and empirical bases are so weak, why did India chose to showcase its regulatory reform efforts, expecting it to boost investment flows to achieve the Make in India goals? If actions speak louder than words, then the government was probably using the EDB ranking as a smoke screen to dilute critical labour laws and investment rules for short-term gains for enterprises. This is not to deny the scope and the need for regulatory rationalisation. However, since the regulations were often introduced to correct for market failures, any efforts at de-regulation have to ensure that they do not lead to additional social costs for enterprises and industrial workers. The evidence of the government’s actions, however, seems to suggest otherwise.

This is illustrated with the recent example of the dilution of The Boilers Act 1923 and Indian Boilers Regulation 1950 that regulate the production and use of industrial boilers as they are concerned with industrial safety. The law earlier required the boiler inspector to periodically inspect factories and certify the safety of boilers in use.

In 2016, as part of improving the EDB ranking and as part of the Make in India (as well as Make in Maharashtra) initiative, the state government diluted boiler inspection requirements by replacing the mandatory government inspection and certification with self-certification by enterprises, complemented by a “third-party certification” by specialist private agencies. To quote the official rule change:

The Government of Maharashtra is in process of rationalisation and simplification of various Labour Laws with underlying objective of ensuring ease of doing business and promote make in Maharashtra drive. Further, the endeavour of the government to ensure removal of various bottlenecks and impediments in obtaining various approaches under the Rules/Law without compromising the safety and security of the workers and peoples engaged in the various industrial processes.

The main objective of scheme [Third party Inspection-Scheme for Boilers/Economisers] is to minimise personal interface and visits of the boiler inspection officers of the Directorate of Steam Boiler without compromising the quality of services to be provided, the industrial establishment using steam boilers will now be able to opt for third party inspection scheme of boilers/economisers...Under the scheme the third party agency and competent person...shall be eligible to undertake inspection of boilers of those industrial units/establishment which have opted for scheme7

Trade bodies and employers’ associations such as the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) hailed the EDB initiative as a progressive move. Maharashtra’s initiative has reportedly been followed in most other states.

What is the evidence on the outcome of the initiative after two years of the rule change? Apparently, none of the factories using boilers (i) have engaged third-party inspectors, or (ii) have submitted self-declaration certificate of the safety of the boilers as required—as reported by the Indian Expressquoting the state labour department officials (January 21, 2019, Mumbai edition).

Surely, for factory owners in Maharashtra, deregulation would have saved money and time spent on boiler inspection and also perhaps (the alleged and often unsaid) the cost of corruption. However, could there be a social cost associated with these private gains of deregulation? Probably yes, as the risks of industrial accidents could have risen on account of unsafe and uncertified boilers in usage. The higher risks get translated into a higher risk premium for such factories and workers working therein, raising the insurance cost for firms, and lowering safety for industrial workers. If this argument is valid, such a policy reform seems myopic for the nation as the long-term costs of running factories could go up, and industrial workers' safety gets jeopardised.

Subject to a fuller verification, this example illustrates how the government is diluting critical industrial safety laws under the guise of improving the EDB index. In other words, the government’s actions perhaps reflect its principal belief that such regulations are avoidable, as market forces would take care of industrial safety and occupational health of workers. Such faith in the virtues of free markets (or market fundamentalism), signals the ruling regime’s commitment to its political slogan, “Minimum Government and Maximum Governance.” Whether freer markets help attain the goals of Make in India seems a different matter.

5 Conclusions

Make in India is a flagship initiative launched in 2014 to raise the manufacturing sector’s share in domestic output and employment, and to enhance national technological capabilities to counter growing import dependence. After nearly five years, the outcomes of the initiative seem modest.

The policy initiative seems premised on the view that excessive regulations constrain factories and firms, hence deregulation could augment investment and output, which would now be guided by market signals. To this end, the government has sought to benchmark its regulatory reforms to the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index. And India’s rank in the index did go up from 142 in 2014 to 77 in 2018.

However, this improvement in rankings failed to achieve the real objective, namely a ratcheting up of industrial performance. Why? India’s faith in the EDB index seems misplaced for many reasons. One, globally, there is no statistically valid association between the EDB index rank (and its improvements) and growth in FDI and private investment. Two, India’s rank improvement is mostly due to methodological changes; with an unchanging methodology the needle barely moved. Three, EDB is an ideologically motivated index: Chile’s EDB Index rank moved up whenever conservatives were in power, and the rank went down during the socialists’ regime.

[T]he aim of improving India’s ranking according to the EDB index was perhaps a mere facade to dismantle critical industrial and labour regulations, disregarding basic economic and social considerations such as market failures, social protection, and workers’ occupational health and safety.

This raises many issues. Why did India stake its policy credibility on a global ranking of doubtful value? One could hazard a guess that the idea underlying the index—that excessive state regulation is the principal hindrance to private initiative—is probably in line with the ruling dispensation’s economic world view, which is best captured in its political slogan “Minimum Government, Maximum Governance”. If our suspicion is correct, then the aim of improving India’s ranking in the EDB index was perhaps a facade to dismantle critical industrial and labour regulations, disregarding basic economic and social considerations such as market failures, social protection, and workers’ occupational health and safety.

Our contention is illustrated with an example of deregulation with potential downside risks for factories and workers. The Maharashtra government’s abolition of compulsory inspection of industrial boilers under the Boilers Act of 1923 by third-party inspection and self-declaration of safety conditions in 2016 is a case in point. The dilution of the law apparently resulted in no inspection at all by specialist private “third-party agents”, and zero self-declaration and certification—thus seriously enhancing risks of industrial accidents. Thus, if the Maharashtra example of deregulation gives us a glimpse of what the Make in India seems to be really about at the ground level, then national industrial progress could be in serious jeopardy.

Granting, for argument’s sake, that less regulation is a desirable end in itself, what is the evidence that such markets deliver sustained industrialisation in current times? Very little, in fact. Historically, many of the industrial and labour regulations were introduced to overcome the short-sighted behaviour of employers and to protect long-term industrial progress. After all, the safety of industrial assets and workers’ lives surely contribute to long-term productivity gains.

To answer the question posed in the sub-title of this article: The lion—Make in India’s ubiquitous emblem—didn’t roar because the policymakers lacked a strategic vision for industrialisation, and failed to make the required investments in technology and organisation. If the history of industrialisation from Japan to China is any guide, they all have followed active industrial policies to forge economic success.8 The recent industrial rise of China with the continued dominant role of state-owned firms, long-term development banks, and restrictions on FDI in high- tech industries clearly show merit in carefully targeted industrialisation efforts.

What is the rationale for such interventions? Modern industries are capital-intensive with immense scale economies. The market for industrial technologies is far from perfect since a few giant global firms dominate them. Industrial policy is not just about overcoming market failures but also about seeking to promote national capabilities in the face of highly unequal access to markets and for technologies. For developing countries to acquire such capabilities, they require considerable sustained state support for long-term finance and a conducive environment for technological learning. Surely while India needs to avoid past mistakes, it needs to build on successful instances of carefully designed policies to promote efficient industries.

Hence, if policymakers are serious about Make in India, there is a need to re-discover and re-imagine industrial policy; not seek quick fixes.