It would be easy to write a story about Venezuela’s energy problems and, in it, focus on the corruption and mismanagement that have taken place. This would make it look like Venezuela’s problems were different from everyone else’s. Taking this approach, it would be easy to argue that the problems wouldn’t have happened, if better leaders had been elected and if those leaders had chosen better policies.

I think that there is far more behind Venezuela’s financial and energy problems than corruption and mismanagement.

As I see the story, Venezuela realized that it had huge oil resources relative to its population, back as early as the 1920s. While these oil resources are substantial, the country misestimated how high a standard of living that these resources could support. To try to work around the issue of setting development goals too high, the country chose the path of distributing the benefits of oil exports in an almost socialistic manner. This socialistic approach, plus increased debt, hid the problem of a standard of living that could not really be supported for many years. Recent problems in Venezuela show that these approaches cannot be permanent solutions. In fact, it seems likely that Venezuela will be one of the first oil-exporting nations to collapse.

How the Subsidy from High-Priced Exported Oil Works

Oil is a strange resource. The cost of oil production tends to be quite low, especially for oil exporters. The selling price is based on a world oil price that changes from day to day, depending on what some would call “demand.” The difference between the selling price and the cost of extraction can make oil exporters rich. In a sense, this difference might be considered an “energy surplus” that is being distributed to the economies of oil exporters. The greater the energy surplus being distributed, the greater the quantity of goods and services (made with energy products) that can be purchased from outside the country with the hard currency that is made available through the sale of oil.

In fact, the existence of such a profitable resource tends to crowd out development of other, less profitable, enterprises. Thus, Venezuela has tended to be a country whose economy revolves around oil. There is a small amount of agriculture and quite a bit of services, but for the most part, the goods used by the economy must be purchased from outside the country. Furthermore, nearly all of the revenue that is available to purchase these goods comes from the sale of oil exports. Thus, the economy tends to follow the fortune of oil sales.

Figure 1 shows a rough estimate of the benefit that Venezuela’s oil exports have provided in inflation-adjusted US dollars. Based on this approach, the per capita benefit from oil exports seems to have peaked very early, in about 1981.

Figure 1. Venezuela per capita value of oil exports, calculated by multiplying Venezuela’s year-by-year quantity of oil exports by the price in 2017$ of oil, and dividing by estimated population. Both price and quantity determined using BP 2018 Statistical Review of World Energy. Population based on 2017 United Nations middle estimates.

The people of Venezuela did not realize that the amount of benefit that oil exports would provide would start falling very early. Instead, leaders set their sights on living standards that would be affordable if the level of subsidy that the economy could obtain from oil exports were to remain as high as during the 1973 to 1981 period.

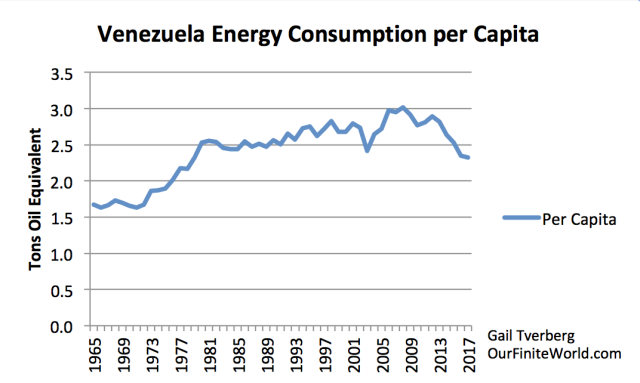

Figure 2 shows how much energy the population, on average, consumed over the 1965 to 2017 period. This figure shows that energy consumption per capita rose dramatically between 1973 and 1981. In this way, citizens were able to benefit from the huge rise in per capita oil export revenue, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2. Energy consumption per capita for Venezuela, based on BP 2018 Statistical Review of World Energy data.

This higher level of energy consumption meant that the economy readjusted in a way that added more goods and services using energy. For example, the economy added paved roads, airports, schools, electricity generating capacity and health care. People came to expect this higher standard of living going forward, even if the level of subsidy that oil exports had been adding was rapidly disappearing.

The way the amounts in Figure 1 “work” is that they depend both on the quantity of oil exported and the market price for that oil. If Venezuela’s oil exports are not rising quickly enough, or if the price of oil is not high enough, the level of oil subsidy fails to rise enough to support the economy. Also, rising population becomes an issue because as population rises, more homes, cars, electricity, streets, and other goods (requiring energy consumption) are needed. Because Venezuela must import practically everything other than oil, it must either (a) export an increasing quantity of oil per year, or (b) get an increasingly high price for the oil it exports, if it wishes to support its rising population at its chosen standard of living.

It became evident very early that Venezuela had set its sights on a living standard that was far higher than it could really support. In the period since 1965, Venezuela’s first debt crisis took place in 1982, as the subsidy suddenly started falling. Later debt crises occurred in 1990, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2004, and 2017. Clearly, as soon as the per capita subsidy started falling in 1982 (see Figure 1), Venezuela’s economy became very troubled. It could not really support its chosen standard of living.

How could Venezuela hide the problem of an unsupportable living standard for over 35 years?

I see three major ways the insupportable living standard could be hidden:

(a) Pushing the problem off into the future using added debt

Nearly everyone is willing to believe that oil prices will rise as high as is needed to extract oil resources that seem to be available with current technology. Would-be lenders are also willing to believe that oil resources can be extracted as rapidly as needed to support the economy. Given this combination of beliefs, Venezuela has had little difficulty adding more debt, even in periods not long after it has been forced to restructure previous debt.

Recently, the biggest lender to Venezuela has been China. With this arrangement, Venezuela has been able to obtain the economic benefit of part of its oil resources, before the oil has actually been extracted. Unfortunately, this arrangement makes Venezuela more quickly susceptible to the adverse impact of a downturn in oil prices. To make matters worse, the debt to China appears to include a provision that creates a lower repayment level (in oil) if prices rise, but creates a higher repayment level (in oil) if oil prices fall. This provision no doubt looked favorable to Venezuela, back in the time period when it was believed that oil prices could only rise.

As far as I know, Venezuela is the only oil exporting country that has used debt as extensively as it has. Some oil exporters, such as Saudi Arabia, have taken the opposite approach, setting aside reserve funds to use in the event that oil prices fall. Needless to say, Venezuela’s use of debt has tended to make its economy very vulnerable to restructuring or defaults if oil prices fall.

(b) Pursuing economic simplification

A complex economy is one that is set up, as much as possible, to keep up with growing technology. A significant share of expenditures go both toward making new capital goods and maintaining existing capital goods. There are considerable differences in pay levels, to make certain that those who are providing technical expertise are adequately compensated for their efforts. Business leaders also are adequately compensated for their contributions.

A much simpler economy, which is what most of the Venezuelan leaders have been aiming for, is an economy in which everyone gets a basic level of housing, transportation, and healthcare, but virtually no one gets very much. There is also not much investment in new technology and new capital goods because nearly all of the hard currency being obtained by selling oil exports is being used to purchased imported goods and services to support the basic level of goods and services (such as roads, electricity, education, and food) being provided to the many citizens of the economy. Since the external value of oil exports sets an upper limit on the quantity of goods and services that Venezuela can import, this leaves virtually no capacity to purchase imported goods and services needed to support new capital investment and research.

In Venezuela’s economy, the cost of both oil and electricity have been kept very low–below the cost of production. This helps keep citizens happy, but it also cuts off funds for new investment in these areas. This, too, is part of the simple economy approach.

One disadvantage of a simple economy is that the low wages for engineers and other professionals encourages these professionals to move to other countries, where compensation is more adequate. Another disadvantage of a simple economy is that it encourages bribery, because graft is a way of adjusting the system so that those who “can make things happen” are adequately compensated for their efforts. The simple economy approach also tends to discourage research and investment in new areas, such as natural gas production and improved methods of heavy oil extraction.

A simple economy can be kept operating for a while, but it quickly reaches limits in many ways:

The limited skill level of residents who have not emigrated for higher wages elsewhere makes the completion of complex projects, such as new electricity generation facilities, difficult.

The inadequate level of oil export revenue puts a limit on the amount of spare parts and other goods needed to maintain the infrastructure, such as electricity transmission.

As existing oil wells deplete, little funding (in hard currency needed for imports) is available to make investments in new wells for extraction.

Research on new techniques for oil extraction is also inhibited.

(c) Neglect of current systems becomes an increasing issue, as the lack of hard currency revenue from oil exports becomes a bigger issue.

Venezuela can, in theory, buy what it needs from abroad, but there is a limit to the total amount of goods and services that can be imported, based on the amount of hard currency funds it obtains from selling crude oil. If the price of oil falls, then Venezuela must, in some way, cut back on goods and services that it had previously supplied. One of the least obvious way of doing this is by cutting back on maintenance and repairs.

The recent long electricity outage in Venezuela seems to be at least partially related to neglect of usual maintenance activities. It seems that Venezuela’s state-owned electrical company failed to keep the brush cleared under electric transmission lines leading away from the very major Guri Dam. It now appears that one of the causes of Venezuela’s recent long electricity outage was damage to transmission lines caused by a brush fire within the Guri complex. This could perhaps have been prevented by better maintenance.

Figure 2 shows that energy consumption per capita has been falling, especially since 2011. This would suggest that standards of living have been falling. Needless to say, if Venezuela’s oil exports drop further, a further reduction in standard of living can be expected.

Why Is America Issuing Sanctions Against Venezuela’s Oil Company PDVSA?

On January 28, 2019, the United States imposed sanctions against Venezuela’s state oil company, PDVSA. The reasons given for these sanctions are the following:

To hold accountable those responsible for Venezuela’s tragic decline in oil supply

To restore democracy

To help prevent further diverting of Venezuela’s assets by Maduro, and thereby preserve those assets for the people of Venezuela

These reasons sound good, but I expect that the primary real reason for the sanctions was to try to take Venezuela’s oil production off line and, through this action, force oil prices higher.

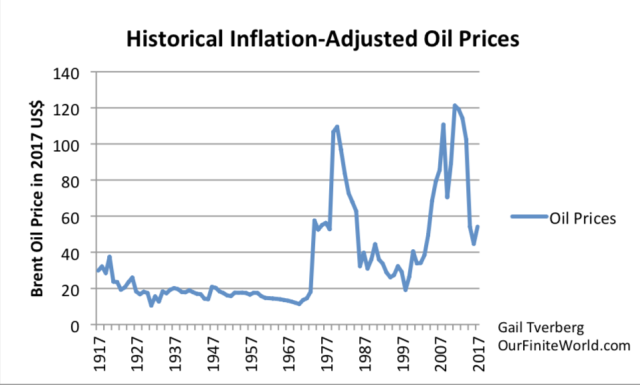

World oil prices have been far too low for oil producers since at least 2014.

Figure 3. Historical inflation-adjusted oil prices, based on inflation adjusted Brent-equivalent oil prices shown in BP 2018 Statistical Review of World Energy.

Many people, thinking about the oil price situation from the consumers’ point of view, are completely unaware of the problem that low oil prices can cause for producers. Oil producers may not go out of business immediately because of low oil prices, but eventually the low prices will cause a cutback in investment, and thus production. Countries that have sold some of their oil production in advance, such as Venezuela, are especially vulnerable.

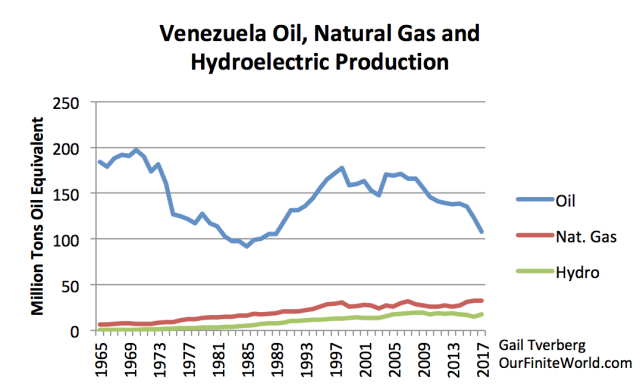

Figure 4. Venezuela’s energy production by type, based on data of BP 2018 Statistical Review of World Energy.

Figure 4 shows that oil production for Venezuela has been dropping for a very long time. Its highest year of production was 1970, the same early high year as for United States’s oil extraction. Natural gas is mostly “associated” gas, which is made available through oil production. Hydroelectric is small in comparison to oil and gas. Hydroelectric production has been generally falling since 2008.

There is a widespread belief among oil executives and politicians that reducing oil production will force oil prices up. I expect to see, at most, a brief spike in oil prices. The major issue is that the world economy is a networked system. Prices for oil and for electricity cannot rise higher than consumers, in the aggregate, can afford. If there is too much wage disparity around the world, the low wages of many workers will tend to hold oil prices down, because these workers cannot afford goods such as smartphones and automobiles made with oil and other energy products. These lower oil prices reflect the fact that the way the economy has been changing in ways that leave less surplus energy to distribute to oil exporters to operate their economies.

The way the networked economy works is determined by the laws of physics, whether we like it or not. As far as I can see, the end of oil extraction comes because oil prices cannot be raised high enough to make extraction profitable. Once oil extraction becomes unprofitable, oil exporting nations will start collapsing. Venezuela is the “canary in the coal mine” in this collapse process, because of the extensive use it has made of debt.

What If Oil Prices Can Be Forced Upward?

If somehow oil prices could be forced up by reducing Venezuela’s exports to practically zero, this would have a double benefit:

More oil from around the world, including the United States, could be profitably extracted, because oil resources that are more expensive to produce would suddenly become profitable.

Venezuela’s oil could be more profitably extracted.

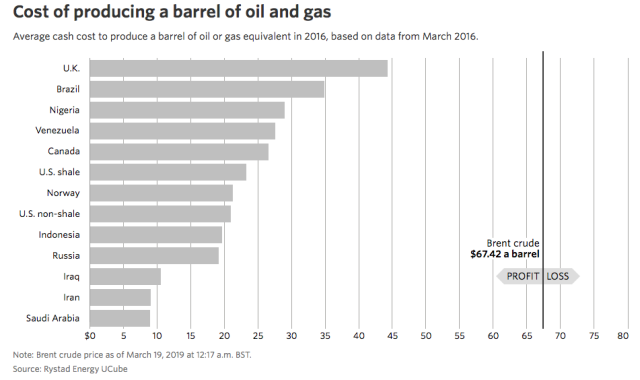

If prices actually rise, and if the United States remains in control of the situation, the US could theoretically expand Venezuela’s oil production. Venezuela has the largest oil reserves of any country in the world. Its expected cost of production is relatively low, if the exports of oil are not expected to support essentially the whole economy. The cost of pulling the oil out of the ground in Venezuela seems to be about $28 per barrel, if we believe a 2016 estimate by Rystad Energy.

Figure 5. Cost of producing a barrel of oil and gas in 2016. WSJ figure based on Rystead Energy analysis.

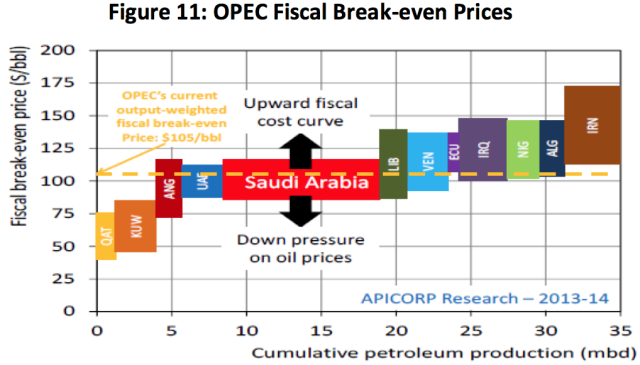

The cost of supporting the entire economy with the revenue from oil exports is far higher. Figure 6 shows that back in 2013-2014, the cost of oil, including the subsidies needed to maintain the operation of the rest of the economy, amounted to about $110 per barrel. I would expect that with all of Venezuela’s debt, the real cost might be even higher than this.

If the US doesn’t plan to support all of Venezuela’s population with the export revenues from oil extraction, it can theoretically extract the oil more economically than the $110 per barrel price that is needed to support the whole economy. Thus, it could get along with a price closer to $28 per barrel.

Furthermore, the investment capabilities and technical expertise of the United States could, at least in theory, ramp up Venezuela’s oil production, if this is desired at some future date. Similarly, “non-associated” natural gas production could be ramped up, if desired, because this seems to be available, but has been neglected.

I expect that all of this development would be more difficult and expensive than a simple comparison such as this seems to suggest. The ultimate problem is that a whole economy needs to be in place to make the extraction possible. Even if a cursory examination suggests that substantial savings are possible, the cost associated with maintaining necessary support services would make the total cost of energy extraction much higher.

Conclusion

Venezuela seems to be the canary in the coal mine with respect to where oil exporters are headed. Other countries will want to push them out of oil production, so as to try to raise prices for themselves. Debt defaults and lack of availability of debt may also become issues.

One item of interest is the fact that in Venezuela, lack of oil revenues can adversely affect electricity supply. Thus, we should not be surprised if electricity supply fails at about the same time that oil production falls. Even electricity supply provided by hydroelectric plants seems to be at risk.

Another item of interest is how Venezuela’s attempt at even distribution of goods and services, using a somewhat socialistic approach is working out. This approach (which is now being advocated by some political candidates) seems to have some short-term benefits, because it tends to keep the population happy–almost everyone seems to have a minimum standard of living. But, over the long term, this approach leads to the loss of the ability to maintain today’s high-tech economy. This approach doesn’t prevent collapse either, because a lack of investment and expertise eventually causes important parts of the system to stop operating.