At its annual investor conference in San Francisco in May 2014, with oil trading at $102 a barrel, Wells Fargo & Co. boasted that in just two years it had almost doubled its energy exposure and seized the title of Wall Street’s top oil and gas banker.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. Crude prices peaked a month later and have since plummeted to $40. Wells Fargo has downgraded 38 percent of its energy loans and set aside $1.2 billion to cover potential losses, according to company filings. The loans are coming under increasing scrutiny from regulators and investors, even though they make up only 2 percent of the bank’s portfolio.

Wells Fargo’s foray into oil shows how Wall Street misjudged the risks hidden in an esoteric type of energy financing long thought to be bulletproof. To fuel the growth of its energy desk, the bank targeted some of the least creditworthy borrowers in the shale patch, offsetting the risk by demanding oil and gas as collateral. This type of financing, known as reserves-based lending, was considered safe because banks historically got back every penny they loaned, even after default, according to a 2013 Standard & Poor’s report.

“The perception was the risk was reasonably low,” Dennis Cassidy, co-head of the oil and gas practice at consulting firm AlixPartners in Dallas, said of reserves-based lending across the industry. “The volume and velocity of deal flow was such that it was a rubber stamp. They were not scrutinizing price assumptions and forecasts. Everyone was open for business. It was full on, full throttle.”

Underwater Loans

This time is different. The growth of the high-yield bond market allowed drillers to take on far more debt than in past booms, leaving them more vulnerable to default. The emergence of shale technology allowed companies to expand reserves and the loans backed by those properties.

Some of those loans may now be underwater. JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc., Bank of America Corp., Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley would need an additional $9 billion to cover souring oil and gas loans in the worst-case scenario, Moody’s Investors Service said in an April 7 report. Lenders could lose 21 cents on the dollar on defaulted exploration and production loans, four times more than the historical average, Moody’s said.

Lenders including San Francisco-based Wells Fargo are in the midst of semiannual reevaluations of reserves-based loans and are cutting credit lines to reflect falling collateral value. Chesapeake Energy Corp. yesterday pledged almost all of its oil and gas reserves, real estate and derivatives contracts to keep its $4 billion credit line.

“We’re all being as appropriately tough to make sure that we protect the interests of the bank,” John Shrewsberry, Wells Fargo’s chief financial officer, said on a January call with analysts. “We were working with each customer to help them work through this. It doesn’t do us any good to accelerate an issue, or to end up as the holder of a number of oil leases as a bank.”

Jessica Ong, a spokeswoman for Wells Fargo, declined to comment.

Tougher Guidelines

Wells Fargo has been the top dealer of high-yield oil and gas debt, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, selling slices of junk-rated loans to regional banks throughout the U.S. as well as to financial institutions in Canada, Europe, Asia and the U.K.

One example: Breitburn Energy Partners LP. Wells Fargo devoted a page of its 2014 presentation to the Los Angeles-based oil and gas producer, which had a market value of almost $2.7 billion at the time. Now it’s worth less than $120 million. The company has drawn down $1.2 billion of a $1.4 billion credit line, filings show. Wells Fargo, the lead bank, sold participation to lenders including Credit Agricole SA, ING Groep NV and Mizuho Bank Ltd.

At the height of the boom in April 2014, after a rapid expansion of reserves-based lending, the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which oversees 1,600 banks and thrifts, published new underwriting guidelines. They were based largely on how such loans performed in previous downturns, and the regulator almost immediately began updating the guidelines, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Last year, after bank examiners marked many energy loans with tougher ratings than lenders thought necessary, the OCC was flooded with appeals, the person said. In September, regulators from the OCC, the Federal Reserve and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. met with dozens of energy bankers at Wells Fargo’s office in Houston.

The disagreement centered on how to rate the risk of reserves-based loans. Banks insisted that, in a worst-case scenario, they’d be made whole by liquidating the properties. Regulators pushed lenders to focus instead on a borrower’s ability to make enough money to repay the loan, according to the person familiar with the discussions. The agency reinforced its position with new guidelines published last month that instructed banks to consider a company’s total debt and its ability to pay it back when gauging a loan’s risk. Bill Grassano, an OCC spokesman, declined to comment.

“The regulators are taking a stronger stance on cash-flow protection rather than collateral coverage,” said Julie Solar, a senior director of financial institution ratings at Fitch Ratings Ltd. “There were a lot of disagreements and a lot of appeals. There’s a difference between the banks’ view of the ultimate risk of loss and the regulators’ view.”

Downgrading Loans

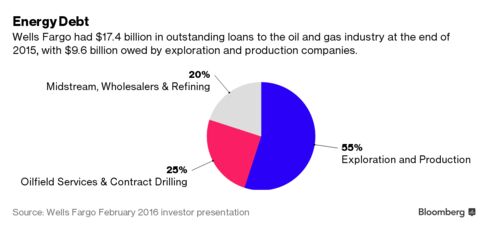

The new guidelines mean banks will have to downgrade loans and set aside more cash to cover losses. Oil and gas producers owed Wells Fargo $9.6 billion at the end of 2015, about 55 percent of the bank’s outstanding energy loans, company filings show. Most of that debt is backed by reserves, the bank has said.

“The tougher standard makes it more expensive for the banks to make loans to the energy business,” said Buddy Clark, a partner with law firm Haynes & Boone in Houston. “But if the banks foreclosed now and tried to sell the properties, they’d have to take a loss. If it happens all at once, it’ll be a disaster where all of these properties come on the market at the same time.”

It’s been a bruising reversal for Wells Fargo. Less than two years have passed since Mike Johnson, then head of commercial lending, told investors the energy business was “a major growth opportunity.” The firm had expanded its energy team to 400 people, with offices in Calgary and Aberdeen, Scotland, and doubled its loan exposure to the industry, he said at the May 2014 event. Wells Fargo had also become the top energy investment bank and had acquired BNP Paribas SA’s energy-lending group in 2012.

“We’d just gone through this very significant recession, and energy was one of the bright spots to invest in,” said AlixPartners’s Cassidy, who predicted an oil bust in 2013 and warned of the financing risks. “It solidified this thesis that oil was a recession-proof commodity. You had enormous growth in energy finance with people who hadn’t ever seen one of these cycles before.”

Spillover Risk

Even a total wipeout isn’t likely to threaten Wells Fargo’s stability. The reserves-based loans, though riskier than expected, will still pay off significantly better than unsecured bonds, where some investors have seen near-complete losses. And if oil prices rise, the collateral value and the cash flow of the borrowers will improve.

Wells Fargo stock, down 13 percent this year, has taken a beating because of energy exposure, but the concerns are overblown, said Tony Scherrer, director of research and portfolio manager for Smead Capital Management in Seattle, which has $2.4 billion in assets including more than 1.5 million Wells Fargo shares.

“They got into energy late,” Sherrer said. “They got excited about it. Was that a mistake? Maybe yes. But what’s the actual exposure? It’s actually pretty small.”

The larger risk is spillover. After the 1980s oil bust, hundreds of lenders failed in oil-dependent states including Oklahoma and Texas as their economies tanked. U.S. oil companies have cut more than 100,000 workers since late 2014, and Oklahoma and Texas are already seeing a rise in credit-card delinquencies and auto-loan defaults. Banks are closely monitoring the housing market and commercial real estate in those regions for signs of cracks in larger parts of their loan portfolios.

Some lenders are pulling back. In 2014, two years after selling its energy unit to Wells Fargo, BNP Paribas, the largest French bank, decided to get back into reserves-based lending. In February, it announced it was abandoning the business for the second time in four years.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.