With late payments on the rise, a dealership upsell begins to look dangerous.

Lured by low interest rates, low gas prices, and a crop of seductive vehicles that are faster, smarter, and more efficient than ever before, American drivers are increasingly riding in style. Don’t be fooled by the curb appeal, though—those swanky machines are heavily leveraged.

Lured by low interest rates, low gas prices, and a crop of seductive vehicles that are faster, smarter, and more efficient than ever before, American drivers are increasingly riding in style. Don’t be fooled by the curb appeal, though—those swanky machines are heavily leveraged.

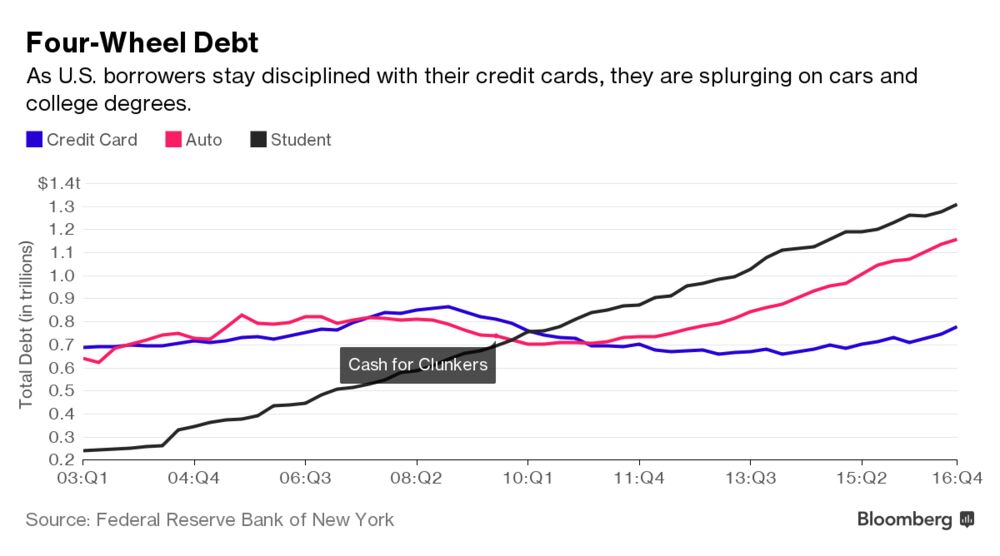

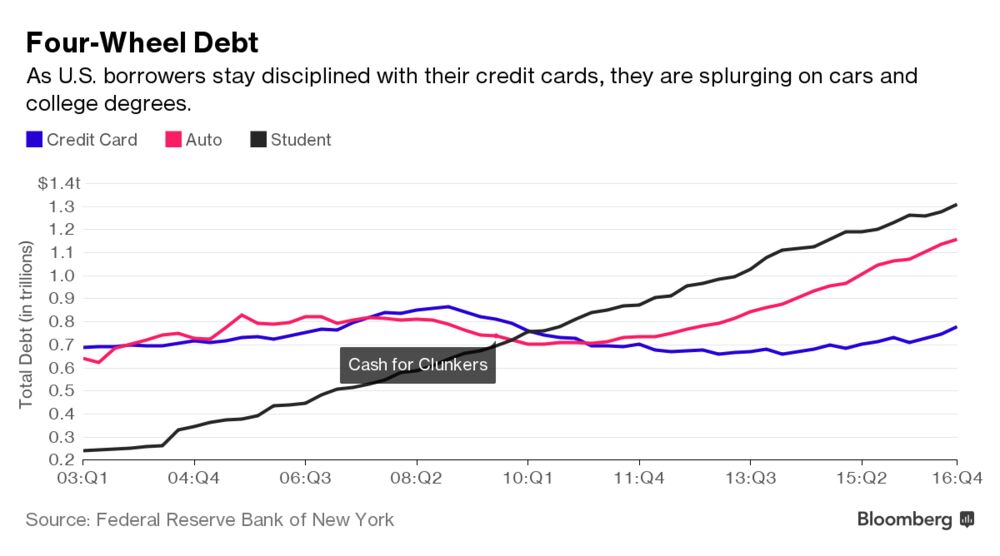

The country’s auto debt hit a record in the fourth quarter of 2016, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, when a rush of year-end car shopping pushed vehicle loans to a dubious peak of $1.16 trillion. The combination of new car smell and new credit woes stretches from Subarus in Maine to Teslas in San Francisco.

It’s an alarming number, big enough to incite talk of a bubble. In fact, the pile of debt would cover the cost of 43.4 million Ford F-150 pickups, one for every eight or so people in the country.

It’s an alarming number, big enough to incite talk of a bubble. In fact, the pile of debt would cover the cost of 43.4 million Ford F-150 pickups, one for every eight or so people in the country.

Another way to look at: Every licensed driver in the U.S., on average, owes about $6,100 in car payments.

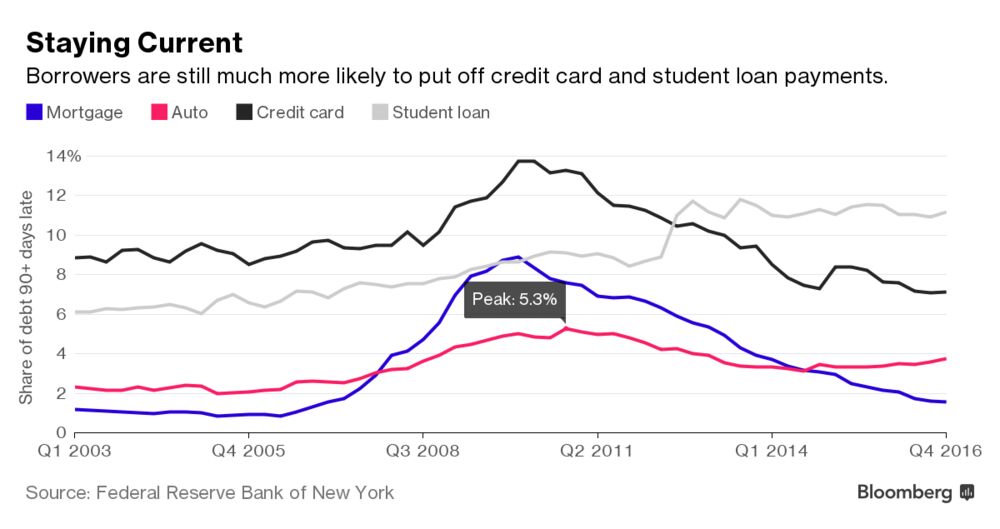

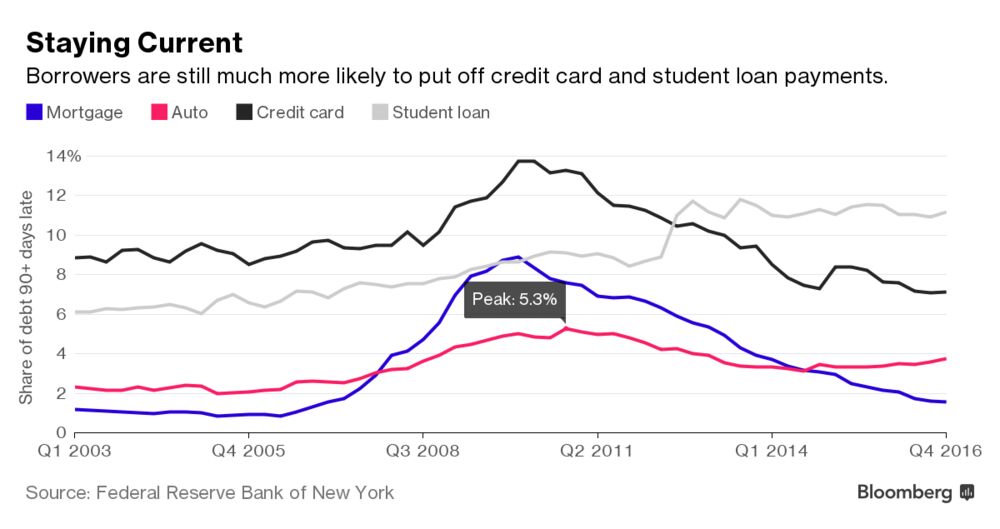

But the market for cars is a lot different than that for houses. For one, vehicles are a much more fluid asset—they are far easier to repossess and resell. What’s more, car payments tend to be cheaper than mortgages and people tend to use their vehicles a lot, so when it comes time to prioritize bills, the auto loan typically takes precedent over other things.

Indeed, delinquencies on vehicle loans, though rising, are still lower than late payments on student loan debt and credit card balances. So preppers getting ready for global economic collapse shouldn’t panic about car payments just yet.

Indeed, delinquencies on vehicle loans, though rising, are still lower than late payments on student loan debt and credit card balances. So preppers getting ready for global economic collapse shouldn’t panic about car payments just yet.

But they should worry—just like executives at the big automakers. Barring a few finance startups, the manufacturers are the ones loaning money to the riskiest buyers. They have more incentive to push a sale and, unlike a bank, make money on both the loan and the product, if all works out right.

Recently, carmakers have been focused on moving SUVs and trucks, which tend to carry higher profit margins than vanilla sedans and cost a little more as well. Lowering credit standards a bit and stretching repayment windows up to six or seven years has helped drive business to record levels, with 17.55 million vehicle sales in all last year.

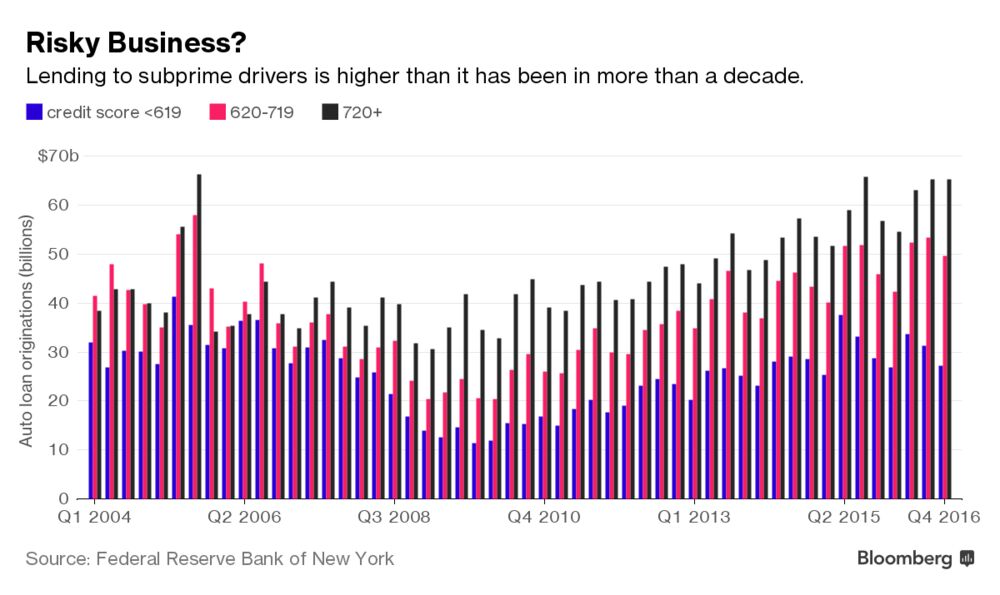

In the past two years, U.S. drivers with credit scores of less than 620 borrowed $244 billion to buy cars, a tally not matched since 2006 and 2007 when the same strata of buyers rolled off with $254 billion in auto loans.

In other words, every time a dealer upsells someone into swanky SUV, they have more in common with the buyer than one might think: both may be paying for it later.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.