Big oil is starting to challenge the biggest utilities in the race to erect wind turbines at sea.

Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Statoil ASA and Eni SpA are moving into multi-billion-dollar offshore wind farms in the North Sea and beyond. They’re starting to score victories against leading power suppliers including Dong Energy A/S and Vattenfall AB in competitive auctions for power purchase contracts, which have developed a specialty in anchoring massive turbines on the seabed.

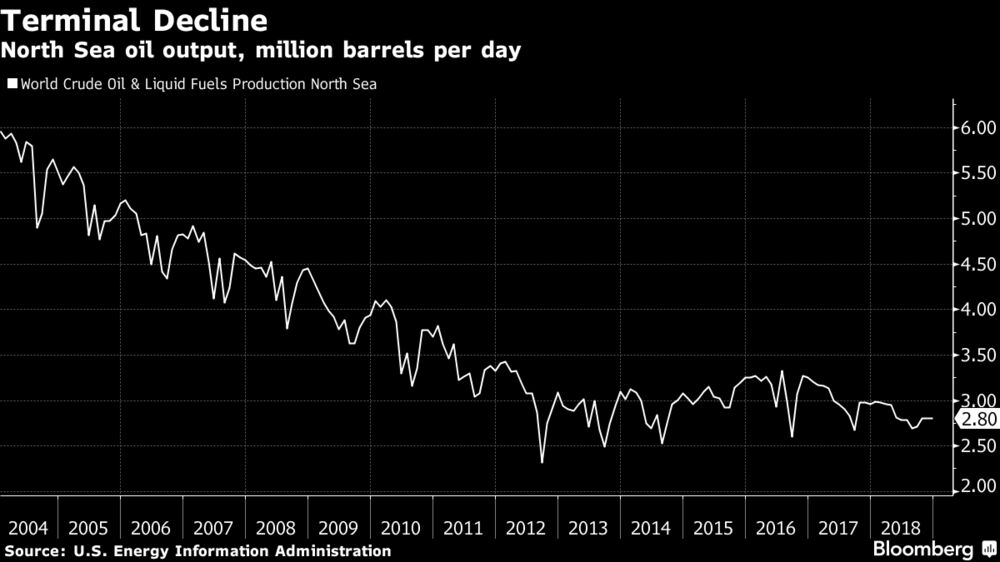

The oil companies have many reasons to move into the industry. They’ve spent decades building oil projects offshore, and that business is winding down in some areas where older fields have drained. Returns from wind farms are predictable and underpinned by government-regulated electricity prices. And fossil fuel executives want to get a piece of the clean-energy business as forecasts emerge that renewables will eat into their market.

“It is certainly an area of interest for us because there are obvious synergies with the traditional oil and gas business,” said Luca Cosentino, the vice president of energy solution at the Italian oil producer Eni, which is working with General Electric Co. on renewables. “As the oil and gas industry we know, we cannot get stuck where we are and wait for someone else to take this leap.”

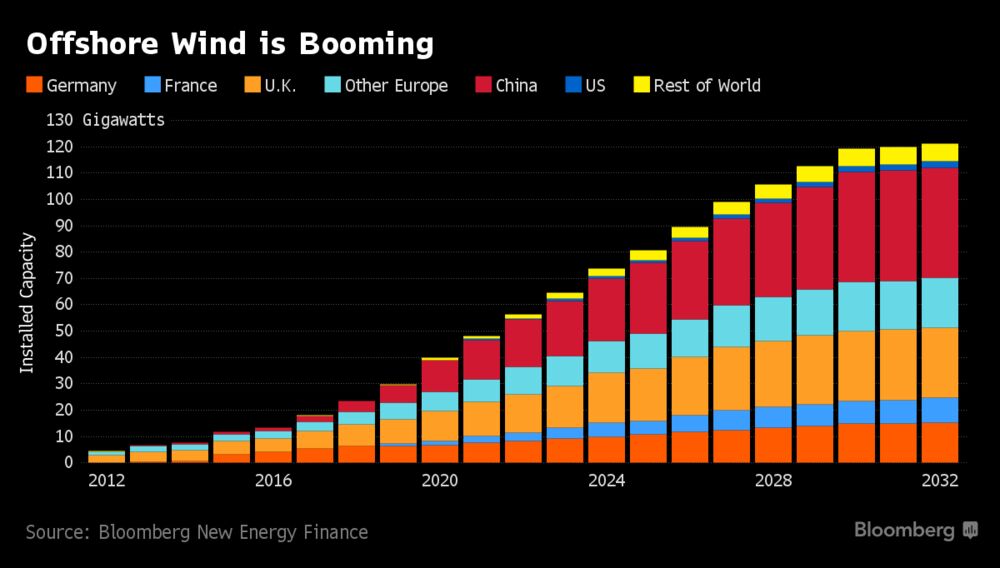

Even as oil production declined in the North Sea over the last 15 years, economic activity has been buoyed by offshore windmills. The notorious winds that menaced generations of roughnecks working on oil platforms have become a boon for a new era of workers asked to install and maintain turbines anchored deep into the seabed. About $99 billion will be invested in North Sea wind projects from 2000 to 2017, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. A decade ago, the industry had projects only a fraction of that size.

While crude still supplies almost a third of the world’s energy, oil executives are starting to adjust to demands for cleaner fuels. Even so, emerging fossil-fuel alternatives including wind and solar power are starting to limit growth in oil demand.

Those technologies and electric cars may displace as much as 13 million barrels of oil a day from global demand by 2040, more than is currently being produced by Saudi Arabia, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

Shell’s Interest

Shell, whose CEO Ben van Beurden has said oil demand may peak in the second half of the next decade, has set up a business unit to identify the clean technologies where it could be most profitable. The company began more than 180 years ago importing shells from Asia and needs to adapt to ensure it’s still around in another century, according to Sinead Lynch, the company’s chair for U.K. businesses.

Wind farms are especially interesting to Shell because they can power electrolysis reactions that make hydrogen, which the company says may be a major fuel for cars in the coming decades, said Lynch in an interview.

It’s exploring new opportunities across Europe in offshore wind after winning contracts from the Dutch government to build the Borssele III and IV wind farms in December. Shell’s bid marked the second cheapest cost for the technology worldwide, according to Lynch, who said the oil major’s big advantage in renewables may be its expertise in marketing.

“It’s also about marketing energy,” Lynch said. “Once you produce your wind, you need to market the power and we have a phenomenally strong marketing and trading business.”

Statoil’s Costs

Oil majors are also changing the offshore wind industry by driving down costs, Statoil Senior Vice President Stephen Bull wrote in an email.

The Norwegian oil major’s Dudgeon wind farm off England’s east coast will be 40 percent cheaper than a neighboring plant built six years ago, Bull said. It’s also creating floating offshore wind foundations that eliminate the costly step of anchoring windmill masts into the seabed. In addition to the U.K., the company is developing projects in Germany and Norway and won a December auction to build an offshore wind farm in New York.

Cost cuts for offshore wind are helping the technology start to compete with traditional forms of energy, especially nuclear, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Current projects entering operation are delivering power at about half the price of farms finished in 2012 thanks to larger turbines and more competition. Costs could fall another 26 percent by 2035, according to the London-based researcher.

The entry of oil majors into renewables is part of “a longer term trend,” according to Nick Gardiner, head of offshore wind at U.K. Green Investment Bank, who notes that companies with the scale of Shell and Eni have the clout to finance projects more cheaply than many of their competitors.

“I don’t think they are doing this just for investor-relation purposes,” said Gunnar Groebler, head of wind at Sweden’s Vattenfall AB, one of the top five offshore wind developers who welcomed the added competition. “Given that these projects are billion-euro investments, I just assume that they will have done their assessments very thoroughly.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.