It has now been over two months since Qatar made the decision to leave OPEC, with many analysts providing informed views on Qatar’s future energy strategy. This article aims to provide an analysis of Qatar’s pivot toward natural gas, and the potential implications for global energy security.

Qatar has long been a key player within the LNG export market, comprising 26.50 percent of global seaborne LNG trade in 2017 (Figure 1). It was likely with this in mind that Saad al-Kaabi, the country’s energy minister, stated that Qatar is leaving OPEC in order to focus on its LNG strategy.

Figure 1: The development of Qatar’s LNG market share, relative to the growth of the global LNG trade.

Conservative projections for the long-term viability of crude, Qatar’s marginal position within the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and its relatively prominent position within LNG markets, culminated in a pragmatic decision to re-focus its policy towards the development of natural gas assets. This article compares the characteristics of both OPEC and the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF), assessing the efficacy of Qatar’s transition towards the development of gas assets.

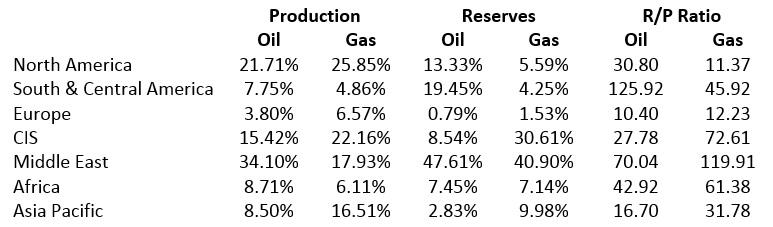

In order to understand how the world's major economies will respond to the growing roll of natural gas as a primary energy source, it is important to first analyse the availability and location of the world's gas reserves. Figure 2 displays OPEC members, GECF members and GECF observers, whilst Table 1 displays production share, reserve share and R/P ratio of crude oil and gas across different regions.

(Click to enlarge)

Figure 2: Left: OPEC members are highlighted in red. Right: A visualisation of GECF members and observers, with members highlighted in red, and observers in orange.

Table 1: The reserve and production shares of each region, for both crude oil and natural gas. The Reserve : Production ratio is also displayed, with high R/P values indicating a low degree of exploitation of a region's reserves.

As is the case with the crude oil trade, the largest natural gas deposits do not correspond with the largest demand centres, prescribing significant international trade of both crude oil and natural gas. However, when comparing the two fuels, it quickly becomes apparent that the overall distribution of natural gas reserves are more concentrated than the distribution of crude oil reserves, in the sense that the three countries that hold the largest natural gas reserves, Russia, Qatar and Iran, have roughly 48.13 percent of the global total, whilst the three countries with the largest crude oil reserves, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and Canada, hold 43.52 percent of world oil reserves. Conversely, when considering the regional distribution of the respective primary energy sources, natural gas is more diverse. The Middle East holds 47.61 percent of global crude oil reserves, as opposed to 40.09 percent of natural gas reserves, with CIS representing a significant region of natural gas reserves at 30.61 percent.

When reviewing the distribution of global reserves from an organisational structure perspective, it becomes clear that OPEC, who's members control 71.93 percent of reserves and 42.40 percent of production, collectively hold substantial influence over the global crude oil market. However, the GECF, which collectively controls 66.45 percent of natural gas reserves and 44.36 percent of production, have historically held a limited collective influence within the global natural gas trade. The GECF's inability to substantially influence the global natural gas market is often attributed to natural gas resources having a higher dispersion than oil reserves, however, when considering both concentration and production ratios, the market structure with respect to supply is somewhat similar.

That said, resource concentration, as characterised by crude oil or natural gas reserves, only provides partial information regarding the ability of a given market participant to exercise market power. The power of a country within a natural resource market is typically linked to the country's exports of that given resource. For example, the USA is the largest producer of natural gas, producing 734.52Bcm of gas in 2017, however, due to its domestic consumption of 739.45Bcm, it remains a net-importer of gas, with a limited ability to exercise market power.

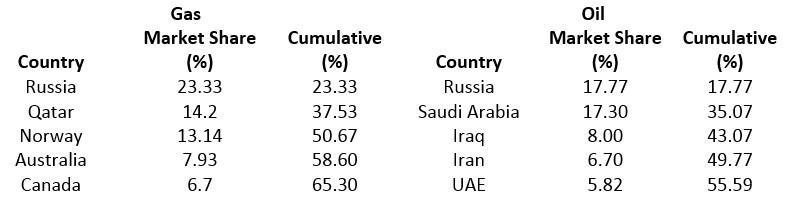

Conversely, Qatar only produced 175.71Bcm of gas in 2017, however it had a comparatively small domestic demand of 47.39Bcm, with its exports of 128.32Bcm ranking second globally in 2017. From this, it becomes clear that countries which have large exports of crude oil or natural gas (Table 2) are considerably more likely to hold dominant market positions than those which hold limited export capacities.

(Click to enlarge)

Table 2: The global distribution of net-exports of crude oil and natural gas, 2017, expressed as a percentage of total exports. Crude oil values include crude, shale oil, oil sands and natural gas liquids (NGLs).

Table 2 shows the distribution of 2017 net-exports of oil and gas. Contrary to popular opinion, the concentration of natural gas exports is substantially larger than crude oil, with concentration ratios between 1-5 systematically larger for gas than oil. Russia acted as the largest exporter of both crude oil and natural gas, with market shares of 17.77 percent and 23.33 percent respectively.

Notably, four of the five largest crude oil exporters are OPEC members, whilst only three of the five largest natural gas exporters are GECF members. Taken at face value, this statistic could be considered misleading, as the three GECF members comprise 50.67 percent of natural gas exports, whereas the four OPEC members only comprise 37.82 percent of the crude oil export market.

The high concentration of natural gas exports observed in Table 2 is due to a number of associated factors, including proximity and physical connectivity to demand centres, contractual structures of natural gas, and low LNG utilization. When considering the five largest gas exporters by percentage of market share, Russia, Norway and Canada are physically connected to large demand centres in Europe and the USA through well-developed distribution infrastructure, whilst Qatar and Australia must operate within the LNG export markets.

In summary, LNG imports from Qatar could provide European consumers with short-run import diversification. However, Qatar, along with other key GECF members, could choose to develop a co-ordinated export strategy, adversely impacting the energy security of European consumers.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.