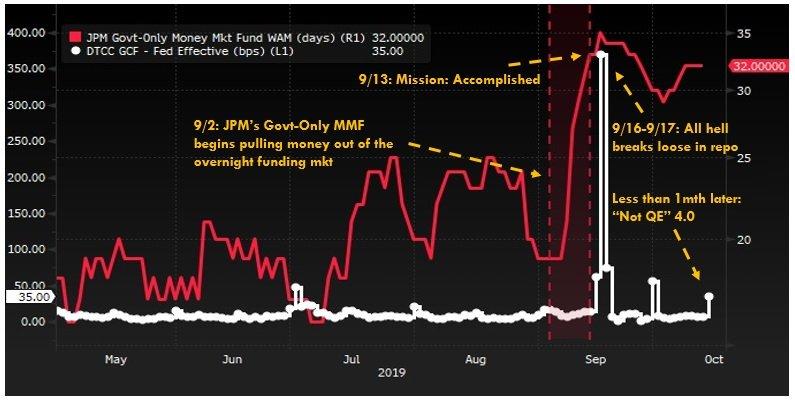

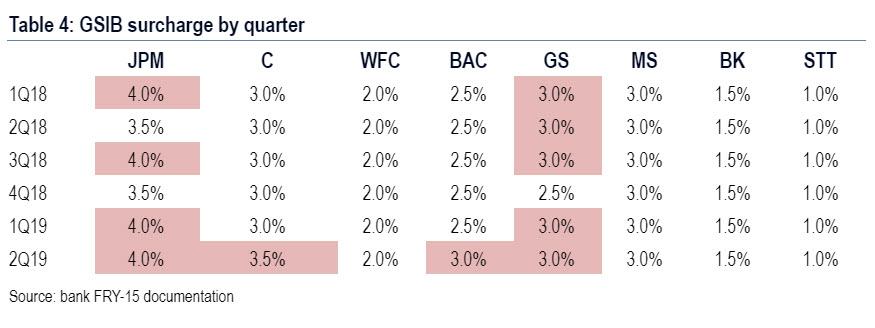

Shortly after our latest discussion how JPM's drain of liquidity via Money Markets and reserves parked at the Fed may have prompted the September repo crisis and subsequent launch of "Not QE" by the Fed in order to reduce its at risk capital and potentially lower its G-SIB charge - currently the highest of all major US banks - we not only got confirmation that the biggest US bank has been quietly rotating out of cash, but was also busy repositioning its balance sheet in another major way.

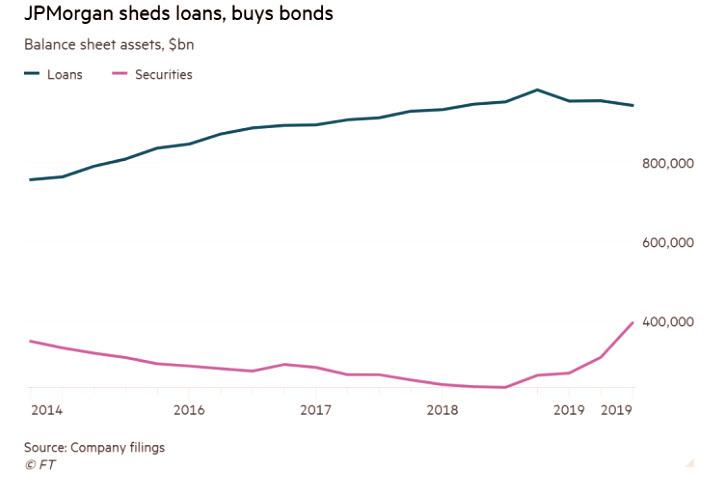

According to an overnight report from the FT which confirms what we already disclosed previously, namely that JPMorgan pushed more than $130bn of excess cash away from reserves in the process significantly tightening overall liquidity in the interbank market, the bulk of this money was allocated to long-dated bonds while cutting the amount of loans it holds, in what the FT dubbed was a "major shift in how the largest US bank by assets manages its enormous balance sheet."

The moves saw the bank’s bond portfolio soar by 50%, and were prompted by capital rules that treat loans as riskier than bonds. And since JPM has been aggressively returning billions of dollars to shareholders in dividends and share buybacks each year, JPMorgan has far less room than most rivals to hold riskier assets, explaining its substantially higher G-SIB surcharge.

An executive at a large institutional investors told the FT that what JPM did "is incredible", adding that "the scale of what JPMorgan is doing is mind-boggling . . . migrating out of cash into securities while loans are flat."

The dramatic change, which occurred gradually over the year, and which may have catalyzed the spike in repo rates in September, was first flagged by JPMorgan at an investor event back in February. Then CFO Marianne Lake said that, after years of industry-leading loan growth, “we have to recognize the reality of the capital regime that we live in”.

So what exactly did JPMorgan do?

The biggest US bank by assets shrank its loans portfolio by 4%, or about $40bn, year to date; at the same time as selling off mortgages, the bank has reduced the amount of cash on its balance sheet and used it to buy long-dated bonds.

And in what may perhaps be a bet that sooner or later the Fed will launch a full-blown QE which again targets mortgage-backed securities, the FT notes that MBS account for the bulk of securities growth; an alternative regulatory reason is that banks can hold much less capital against mortgage bonds than the underlying home loans themselves.

Commenting on JPM's strategist capital reallocation, Jeffery Harte of Sandler O’Neill said that JPMorgan’s revisewd approach "comes down to an economic decision: they can make more money selling [loans] than buying them."

As the FT notes, Bank of America, JPM's closest competitor, has more headroom under the Federal Reserve’s capital rules and continues to grow its loan portfolio. It has added $43bn in loans so far in 2019, largely but not exclusively mortgages. The contrasting strategy, analysts said, reflects its larger cushion under the Federal Reserve’s stress-testing regime.

And while JPMorgan continues to generate strong profits "and could add more risk to its balance sheet if it wanted to" it prefers to send the ample money it generates back to its shareholders. As a reminder, as disclosed during the latest stress test, JPM's plans for the year ahead include $32bn in buybacks and dividends, more than the total net income the bank earned last year.

Steven Chubak of Wolfe Research said that JPMorgan "is doing the right thing given its idiosyncratic capital constraints," but the greater freedom afforded to BofA means it has "more capacity to grow loans which typically generate a higher spread" — and as such more room for profit growth

Others are more skeptical: according to Charles Peabody of Portales Partners, who projects a bleak outlook for the banking industry, sees JPMorgan’s balance sheet choices as part of a larger risk-reduction strategy. The bank, he said, was "acting like the [next] recession is here — everything the bank is doing points that way."

That's certainly true, but the bigger picture here is just as fascinating: in order to boost interbank funding, and to force the Fed to inject more liquidity into the system, JPM first drained reserves and hit money markets...

... which in turn forced the Fed to boost its balance sheet by a whopping $250 billion in just the past 7 weeks as we noted earlier.

In other words, to ensure that JPM's tens of billions in buybacks and dividends continue flowing smoothly and enriching the company's shareholders, Jamie Dimon may have held the entire US financial system hostage, forcing the Fed's hand to restart "Not QE."

Well done, Jamie.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.