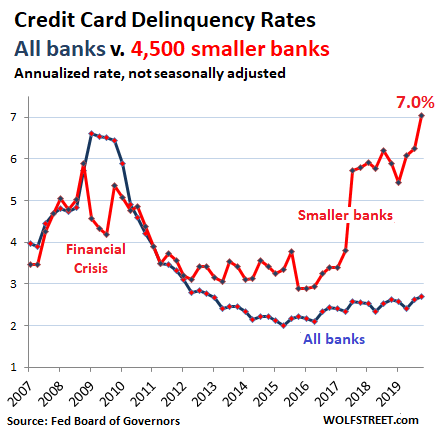

The rate of credit card balances that are 30 days or more delinquent at the 4,500 or so commercial banks that are smaller than the top 100 banks spiked to 7.05% in the fourth quarter, the highest delinquency rate in the data going back to the 1980s (red line).

But at the largest 100 banks, the credit-card delinquency rate was 2.48%, which kept the overall credit-card delinquency rate at all commercial banks at 2.7% (blue line), though it was the highest since 2012, according to the Federal Reserve.

What’s going on here, with this bifurcation of the delinquency rates and what does that tell us about consumers?

Clearly, those consumers that have obtained credit cards at the smaller banks are in a heap of trouble and are falling behind at a historically high rate. But consumers that got their credit cards at the big banks – lured by 2% cash-back offers and other benefits that are being heavily promoted to consumers with top credit scores – do not feel the pain.

A similarly disturbing trend is going on with auto loans. Seriously delinquent auto loans jumped to 4.94% of total auto loans and leases outstanding. This is higher than the delinquency rate in Q3 2010 amid the worst unemployment crisis since the Great Depression. On closer inspection, there was that bifurcation again; prime-rated loans had historically low delinquency rates; but a shocking 23% of all subprime loans were 90+ days delinquent.

During the Financial Crisis, delinquencies on credit cards and auto loans were soaring because over 10 million people had lost their jobs and they couldn’t make their payments.

But these are the good times – with the unemployment rate near historic lows. And yet, there are these skyrocketing delinquency rates in the subprime subset of credit cards and auto loans. It means these people are working, and they’re falling behind their debts.

Consumers with subprime credit scores (below 620) can still get credit cards, but under subprime terms – namely interest rates of 25% or 30% or more.

These rates comes at a time when, according to the FDIC, banks’ average cost of funding was around 1.0%. The difference between a bank’s average cost of funding and the interest it charges is its net interest margin. For banks, subprime credit-card balances, with interest rates of 30%, are the most profitable assets out there.

To get these profits, banks take big risks. Even when a portion of those credit card accounts have to be written off and sold for cents on the dollar to a collection agency, they’re still profitable overall. In addition, banks offload part of the subprime risk to investors by securitizing these subprime credit-card loans into asset backed securities. And investors love them and chase after them for the slightly higher yield they offer.

So I’m not worried about the banks or the investors. If they take a beating, so be it. But what does it tell us about the consumers?

The largest 100 banks have a delinquency rate of just 2.48%, which is low by historical standards. With their sophisticated marketing, they go aggressively after consumers with high credit scores and high incomes, and to get them, the big banks offer big benefits, and so a bidding war has broken out for these high-credit-score consumers, with “2% cash back on every purchase” and other benefits that small banks cannot offer.

These big banks have most of the customers and most of the credit card balances (assets for the banks). Their special offers rope in the lion’s share of consumers with top credit scores. They also issue credit cards to consumers with subprime credit scores. But since these big banks have the lion’s share of prime-rated customers, their subprime customers, when they default, don’t weigh heavily in the mix.

Smaller banks can’t offer the same incentives and don’t have the marketing resources the big banks have. But subprime-rated customers are easy to hand a credit card that comes with few incentives and charges a 30% interest. And those credit card balances, producing 30% interest income, do wonders for a small bank’s bottom line. Proportionately, these small banks end up with more subprime customers. And in this way, they become a gauge for subprime credit card delinquencies.

So why are these delinquencies spiking now? We haven’t seen millions of people getting laid off. These are the good times.

It’s a sign of the sharp bifurcation of the economy for consumers. One group of consumers is doing well. They have rising incomes, and they can afford the surging home prices, the surging healthcare costs, and the surging new-vehicle prices. Those price increases are not reflected in the inflation measures. For example, the price of a Ford F-150 XLT has skyrocketed 163% since 1990 while the official CPI for new vehicles over the same period has increased only 22% thanks to “hedonic quality adjustments” and other adjustments (here is my pickup truck price index chart that overlays both).

Same with used cars. The official CPI for used cars has declined by 11% since 1995, an amazing feat of hedonic quality adjustments, as actual used-car prices have soared since 1995.

There are other consumers whose incomes have not budged much – maybe it went up in line with CPI, but CPI doesn’t reflect actual price increases of cars and homes and other items. Everything big they’re trying to buy or rent or use has soared in price – new and used vehicles, housing, healthcare, education, etc. And those consumers, though they’re working hard, are getting squeezed. That’s the bifurcation.

These are the people that are strung out. They have jobs but are living from paycheck to paycheck, and not because they’re splurging but because, at their level of the economy, prices of basic goods and services have run away from them.

And this can happen from one day to the next, for example when the landlord raises the rent by 15%, or when the car turns into a hopeless heap and has to be replaced, or when the insurance premium jumps 25%, or when the kid ends up in the emergency room. Or a combination. And suddenly, there is no money left to make the minimum payment on the credit card.

And this is happening while people are working. This subgroup of consumers that are getting squeezed is growing, and their problems are growing, and their credit-card delinquencies and auto-loan delinquencies are spiking into the stratosphere like never before – while many other consumers have the best years of their lives, relishing with gusto the out-of-control “speculative energy,” the blistering highs in the stock market, and the surging prices of their homes, vacation homes, and investment properties. And that’s the bifurcation that we’re seeing in the chart above.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.