Summary

- The Eurodollar system is a critical but often misunderstood driver of global financial markets: its importance cannot be understated.

- Its origins are shrouded in mystery and intrigue; its operations are invisible to most; and yet it controls us in many ways. We will attempt to enlighten readers on what it is and what it means.

- However, it is also a system under huge structural pressures – and as such we may be about to experience a profound paradigm shift with key implications for markets, economies, and geopolitics.

- Recent Fed actions on swap lines and repo facilities only underline this fact rather than reducing its likelihood

What is The Matrix?

A new world-class golf course in an Asian country financed with a USD bank loan. A Mexican property developer buying a hotel in USD. A European pension company wanting to hold USD assets and swapping borrowed EUR to do so. An African retailer importing Chinese-made toys for sale, paying its invoice in USD.

All of these are small examples of the multi-faceted global Eurodollar market. Like The Matrix, it is all around us, and connects us. Also just like The Matrix, most are unaware of its existence even as it defines the parameters we operate within. As we shall explore in this special report, it is additionally a Matrix that encompasses an implicit power struggle that only those who grasp its true nature are cognizant of.

Moreover, at present this Matrix and its Architect face a huge, perhaps existential, challenge.

Yes, it has overcome similar crises before...but it might be that the Novel (or should we say ‘Neo’?) Coronavirus is The One.

So, here is the key question to start with: What is the Eurodollar system?

For Neo-phytes

The Eurodollar system is a critical but often misunderstood driver of global financial markets: its importance cannot be understated. While most market participants are aware of its presence to some degree, not many grasp the extent to which it impacts on markets, economies,…and geopolitics - indeed, the latter is particularly underestimated.

Yet before we go down that particular rabbit hole, let’s start with the basics. In its simplest form, a Eurodollar is an unsecured USD deposit held outside of the US. They are not under the US’ legal jurisdiction, nor are they subject to US rules and regulations.

To avoid any potential confusion, the term Eurodollar came into being long before the Euro currency, and the “euro” has nothing to do with Europe. In this context it is used in the same vein as Eurobonds, which are also not EUR denominated bonds, but rather debt issued in a different currency to the company of that issuing. For example, a Samurai bond--that is to say a bond issued in JPY by a nonJapanese issuer--is also a type of Eurobond.

As with Eurobonds, eurocurrencies can reflect many different underlying real currencies. In fact, one could talk about a Euroyen, for JPY, or even a Euroeuro, for EUR. Yet the Eurodollar dwarfs them: we shall show the scale shortly.

More(pheous) background

So how did the Eurodollar system come to be, and how has it grown into the behemoth it is today? Like all global systems, there are many conspiracy theories and fantastical claims that surround the birth of the Eurodollar market. While some of these stories may have a grain of truth, we will try and stick to the known facts.

A number of parallel events occurred in the late 1950s that led to the Eurodollar’s creation – and the likely suspects sound like the cast of a spy novel. The Eurodollar market began to emerge after WW2, when US Dollars held outside of the US began to increase as the US consumed more and more goods from overseas. Some also cite the role of the Marshall Plan, where the US transferred over USD12bn (USD132bn equivalent now) to Western Europe to help them rebuild and fight the appeal of Soviet communism.

Of course, these were just USD outside of the US and not Eurodollars. Where the plot thickens is that, increasingly, the foreign recipients of USD became concerned that the US might use its own currency as a power play. As the Cold War bit, Communist countries became particularly concerned about the safety of their USD held with US banks. After all, the US had used its financial power for geopolitical gains when in 1956, in response to the British invading Egypt during the Suez Crisis, it had threatened to intensify the pressure on GBP’s peg to USD under Bretton Woods: this had forced the British into a humiliating withdrawal and an acceptance that their status of Great Power was not compatible with their reduced economic and financial circumstances.

With rising fears that the US might freeze the Soviet Union’s USD holdings, action was taken: in 1957, the USSR moved their USD holdings to a bank in London, creating the first Eurodollar deposit and seeding our current UScentric global financial system – by a country opposed to the US in particular and capitalism in general.

There are also alternative origin stories. Some claim the first Eurodollar deposit was made during the Korean War with China moving USD to a Parisian bank.

Meanwhile, the Eurodollar market spawned a widely-known financial instrument, the London Inter Bank Offer Rate, or LIBOR. Indeed, LIBOR is an offshore USD interest rate which emerged in the 1960s as those that borrowed Eurodollars needed a reference rate for larger loans that might need to be syndicated. Unlike today, however, LIBOR was an average of offered lending rates, hence the name, and was not based on actual transactions as the first tier of the LIBOR submission waterfall is today.

Dozer and Tank

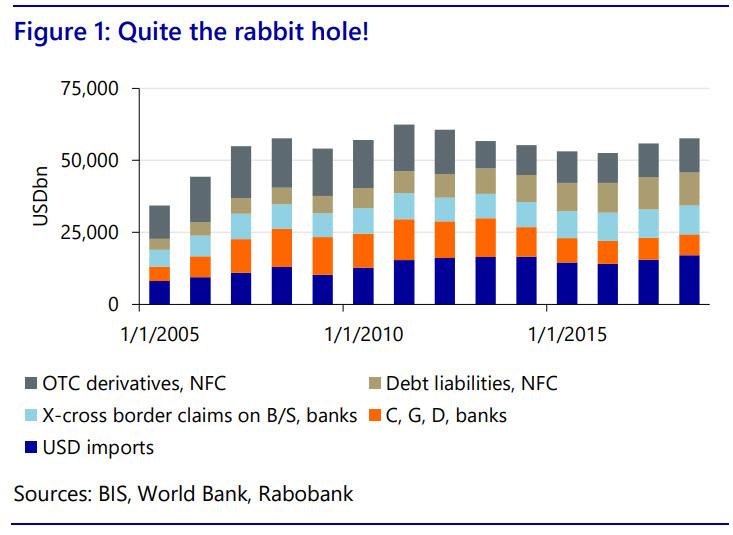

So how large is the Eurodollar market today? Like the Matrix - vast. As with the origins of the Eurodollar system, itself nothing is transparent. However, we have tried to estimate an indicative total using Bank for International Settlements (BIS) data for:

- On-balance sheet USD liabilities held by non-US banks;

- USD Credit commitments, guarantees extended, and derivatives contracts of non-US banks (C, G, D);

- USD debt liabilities of non-US non-financial corporations;

- Over-the-Counter (OTC) USD derivative claims of non-US non-financial corporations; and

- Global goods imports in USD excluding those of the US and intra-Eurozone trade.

The results are as shown below as of end-2018: USD57 trillion, nearly three times the size of the US economy before it was hit by the COVID-19 virus. Even if this measure is not complete, it underlines the scale of the market.

It also shows its vast power in that this is an equally large structural global demand for USD. Every import, bond, loan, credit guarantee, or derivate needs to be settled in USD.

Indeed, fractional reserve banking means that an initial Eurodollar can be multiplied up (e.g., Eurodollar 100m can be used as the base for a larger Eurodollar loan, and leverage increased further). Yet non-US entities are NOT able to conjure up USD on demand when needed because they don’t have a central bank behind them which can produce USD by fiat, which only the Federal Reserve can.

This power to create the USD that everyone else transacts and trades in is an essential point to grasp on the Eurodollar – which is ironically also why it was created in the first place!

Tri-ffi-nity

Given the colourful history, ubiquitous nature, and critical importance of the Eurodollar market, a second question then arises: Why don’t people know about The Matrix?

The answer is easy: because once one is aware of it, one immediately wishes to have taken the Blue Pill instead.

Consider what the logic of the Eurodollar system implies. Global financial markets and the global economy rely on the common standard of the USD for pricing, accounting, trading, and deal making. Imagine a world with a hundred different currencies – or even a dozen: it would be hugely problematic to manage, and would not allow anywhere near the level of integration we currently enjoy.

However, at root the Eurodollar system is based on using the national currency of just one country, the US, as the global reserve currency. This means the world is beholden to a currency that it cannot create as needed.

When a crisis hits, as at present, everyone in the Eurodollar system suddenly realizes they have no ability to create fiat USD and must rely on national USD FX reserves and/or Fed swap lines that allow them to swap local currency for USD for a period. This obviously grants the US enormous power and privilege.

The world is also beholden to US monetary policy cycles rather than local ones: higher US rates and/or a stronger USD are ruinous for countries that have few direct economic or financial links with the US. Yet the US Federal Reserve generally shows very little interest in global economic conditions – though that is starting to change, as we will show shortly.

A second problem is that the flow of USD from the US to the rest of the world needs to be sufficient to meet the inbuilt demand for trade and other transactions. Yet the US is a relatively smaller slice of the global economy with each passing year. Even so, it must keep USD flowing out or else a global Eurodollar liquidity crisis will inevitably occur.

That means that either the US must run large capital account deficits, lending to the rest of the world; or large current account deficits, spending instead.

Obviously, the US has been running the latter for many decades, and in many ways benefits from it. It pays for goods and services from the rest of the world in USD debt that it can just create. As such it can also run huge publicor private-sector deficits – arguably even with the multitrillion USD fiscal deficits we are about to see.

However, there is a cost involved for the US. Running a persistent current-account deficit implies a net outflow of industry, manufacturing and related jobs. The US has obviously experienced this for a generation, and it has led to both structural inequality and, more recently, a backlash of political populism wanting to Make America Great Again.

Indeed, if one understands the structure of the Eurodollar system one can see that it faces the Triffin Paradox. This was an argument first made by Robert Triffin in 1959 when he correctly predicted that any country forced to adopt the role of global reserve currency would also be forced to run ever-larger currency outflows to fuel foreign appetite – eventually leading to the breakdown of the system as the cost became too much to bear.

Moreover, there is another systemic weakness at play: realpolitik. Atrophying of industry undermines the supply chains needed for the defence sector, with critical national security implications. The US is already close to losing the ability to manufacture the wide range of products its powerful armed forces require on scale and at speed: yet without military supremacy the US cannot long maintain its multi-dimensional global power, which also stands behind the USD and the Eurodollar system.

This implies the US needs to adopt (military-) industrial policy and a more protectionist stance to maintain its physical power – but that could limit the flow of USD into the global economy via trade. Again, the Eurodollar system, like the early utopian version of the Matrix, seems to contain the seeds of its own destruction.

Indeed, look at the Eurodollar logically over the long term and there are only three ways such a system can ultimately resolve itself:

- The US walks away from the USD reserve currency burden, as Triffin said, or others lose faith in it to stand behind the deficits it needs to run to keep USD flowing appropriately;

- The US Federal Reserve takes over the global financial system little by little and/or in bursts; or

- The global financial system fragments as the US asserts primacy over parts of it, leaving the rest to make their own arrangements.

See the Eurodollar system like this, and it was always when and not if a systemic crisis occurs – which is why people prefer not focus on it all even when it matters so much. Yet arguably this underlying geopolitical dynamic is playing out during our present virus-prompted global financial instability.

Down the rabbit hole

But back to the rabbit hole that is our present situation. While the Eurodollar market is enormous one also needs to look at how many USD are circulating around the world outside the US that can service it if needed. In this regard we will look specifically at global USD FX reserves.

It’s true we could also include US cash holdings in the offshore private sector. Given that US banknotes cannot be tracked no firm data are available, but estimates range from 40% - 72% of total USD cash actually circulates outside the country. This potentially totals hundreds of billions of USD that de facto operate as Eurodollars. However, given it is an unknown total, and also largely sequestered in questionable cash-based activities, and hence are hopefully outside the banking system, we prefer to stick with centralbank FX reserves.

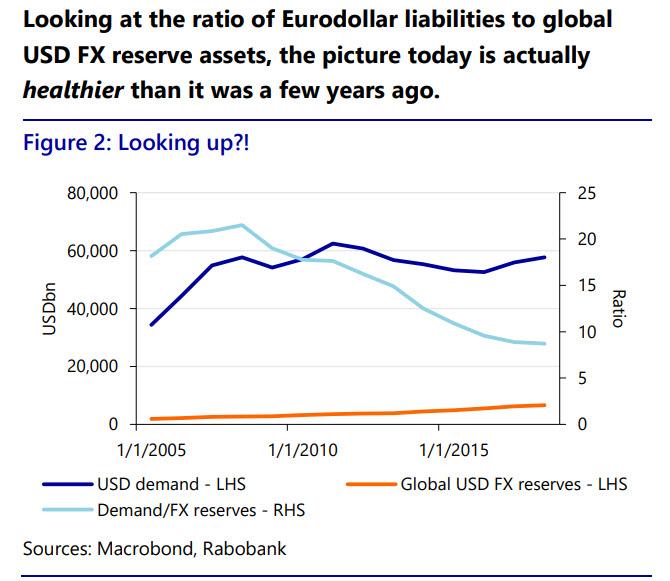

Looking at the ratio of Eurodollar liabilities to global USD FX reserve assets, the picture today is actually healthier than it was a few years ago.

Indeed, while the Eurodollar market size has remained relatively constant in recent years, largely as banks have been slow to expand their balance sheets, the level of global USD FX reserves has risen from USD1.9 trillion to over USD6.5 trillion. As such, the ratio of structural global USD demand to that of USD supply has actually declined from near 22 during the global financial crisis to around 9.

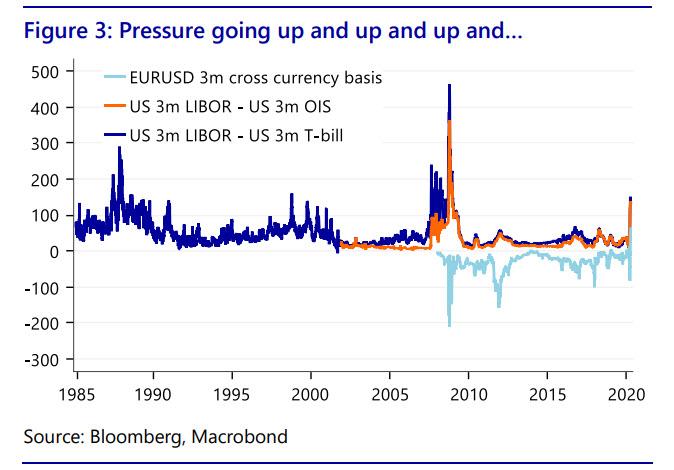

Yet the current market is clearly seeing major Eurodollar stresses – verging on panic.

Fundamentally, the Eurodollar system is always short USD, and any loss of confidence sees everyone scramble to access them at once – in effect causing an invisible international bank run. Indeed, the Eurodollar market only works when it is a constant case of “You-Roll-Over Dollar”.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 and its huge economic damage and uncertainty mean that global confidence has been smashed, and our Eurodollar Matrix risks buckling as a result.

The wild gyrations recently experienced in even major global FX crosses speak to that point, to say nothing of the swings seen in more volatile currencies such as AUD, and in EM bellwethers such as MXN and ZAR. FX basis swaps and LIBOR vs. Fed Funds (so offshore vs. onshore USD borrowing rates) say the same thing. Unsurprisingly, the IMF are seeing a wide range of countries turning to them for emergency USD loans.

The Fed has, of course, stepped up. It has reduced the cost of accessing existing USD swap lines--where USD are exchanged for other currencies for a period of time--for the Bank of Canada, Bank of England, European Central Bank, and Swiss National Bank; and another nine countries were given access to Fed swap lines with Australia, Brazil, South Korea, Mexico, Singapore, and Sweden all able to tap up to USD60bn, and USD30bn available to Denmark, Norway, and New Zealand. This alleviates some pressure for some markets – but is a drop in the ocean compared to the level of Eurodollar liabilities.

The Fed has also introduced a new FIMA repo facility. Essentially this allows any central bank, including emerging markets, to swap their US Treasury holdings for USD, which can then be made available to local financial institutions. To put it bluntly, this repo facility is like a swap line but with a country whose currency you don't trust.

Allowing a country to swap its Treasuries for USD can alleviate some of the immediate stress on Eurodollars, but when the swap needs to be reversed the drain on reserves will still be there. Moreover, Eurodollar market participants will now not be able to see if FX reserves are declining in a potential crisis country. Ironically, that is likely to see less, not more, willingness to extend Eurodollar credit as a result.

You have two choices, Neo

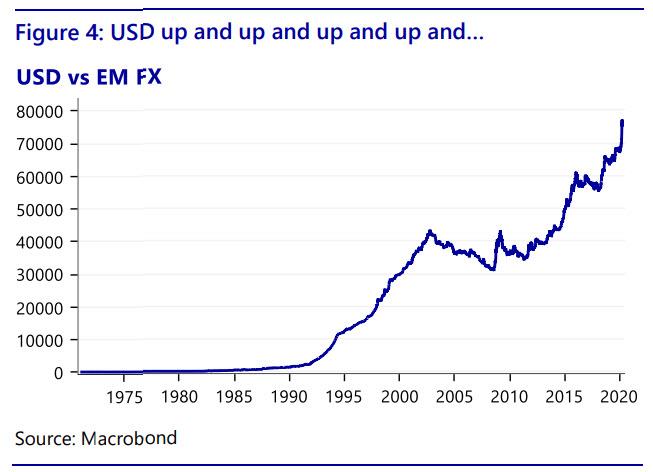

Yet despite all the Fed’s actions so far, USD keeps going up vs. EM FX. Again, this is as clear an example as one could ask for of structural underlying Eurodollar demand.

Indeed, we arguably need to see even more steps taken by the Fed – and soon. To underline the scale of the crisis we currently face in the Eurodollar system, the BIS concluded at the end of a recent publication on the matter:

“...today’s crisis differs from the 2008 GFC, and requires policies that reach beyond the banking sector to final users. These businesses, particularly those enmeshed in global supply chains, are in constant need of working capital, much of it in dollars. Preserving the flow of payments along these chains is essential if we are to avoid further economic meltdown.Channeling dollars to non-banks is not straightforward. Allowing non-banks to transact with the central bank is one option, but there are attendant difficulties, both in principle and in practice. Other options include policies that encourage banks to fill the void left by market based finance, for example funding for lending schemes that extend dollars to non-banks indirectly via banks.”

In other words, the BIS is making clear that somebody (i.e., the Fed) must ensure that Eurodollars are made available on massive scale, not just to foreign central banks, but right down global USD supply chains. As they note, there are many practical issues associated with doing that – and huge downsides if we do not do so. Yet they overlook that there are huge geopolitical problems linked to this step too.

Notably, if the Fed does so then we move rapidly towards logical end-game #2 of the three possible Eurodollar outcomes we have listed previously, where the Fed de facto takes over the global financial system. Yet if the Fed does not do so then we move towards end-game #3, a partial Eurodollar collapse.

Of course, the easy thing to assume is that the Fed will step up as it has always shown a belated willingness before, and a more proactive stance of late. Indeed, as the BIS shows in other research, the Fed stepped up not just during the Global Financial Crisis, but all the way back to the Eurodollar market of the 1960s, where swap lines were readily made available on large scale in order to try to reduce periodic volatility.

However, the scale of what we are talking about here is an entirely new dimension: potentially tens of trillions of USD, and not just to other central banks, or to banks, but to a panoply of real economy firms all around the Eurodollar universe.

As importantly, this assumes that the Fed, which is based in the US, wants to save all these foreign firms. Yet does the Fed want to help Chinese firms, for example? It may traditionally be focused narrowly on smoothly-functioning financial markets, but is that true of a White House that openly sees China as a “strategic rival”, which wishes to onshore industry from it, and which has more interest in having a politically-compliant, not independent Fed? Please think back to the origins of Eurodollars - or look at how the US squeezed its WW2 ally UK during the 1956 Suez Crisis, or how it is using the USD financial system vs. Iran today.

Equally, this assumes that all foreign governments and central banks will want to see the US and USD/Eurodollar cement their global financial primacy further. Yes, Fed support will help alleviate this current economic and brewing financial crisis – but the shift of real power afterwards would be a Rubicon that we have crossed.

Specifically, would China really be happy to see its hopes of CNY gaining a larger global role washed away in a flood of fresh, addictive Eurodollar liquidity, meaning that it is more deeply beholden to the US central bank? Again, please think back to the origins of Eurodollars, to Suez, and to how Iran is being treated – because Beijing will. China would be fully aware that a Fed bailout could easily come with political strings attached, if not immediately and directly, then eventually and indirectly. But they would be there all the same.

One cannot ignore or underplay this power struggle that lies within the heart of the Eurodollar Matrix.

I know you’re out there

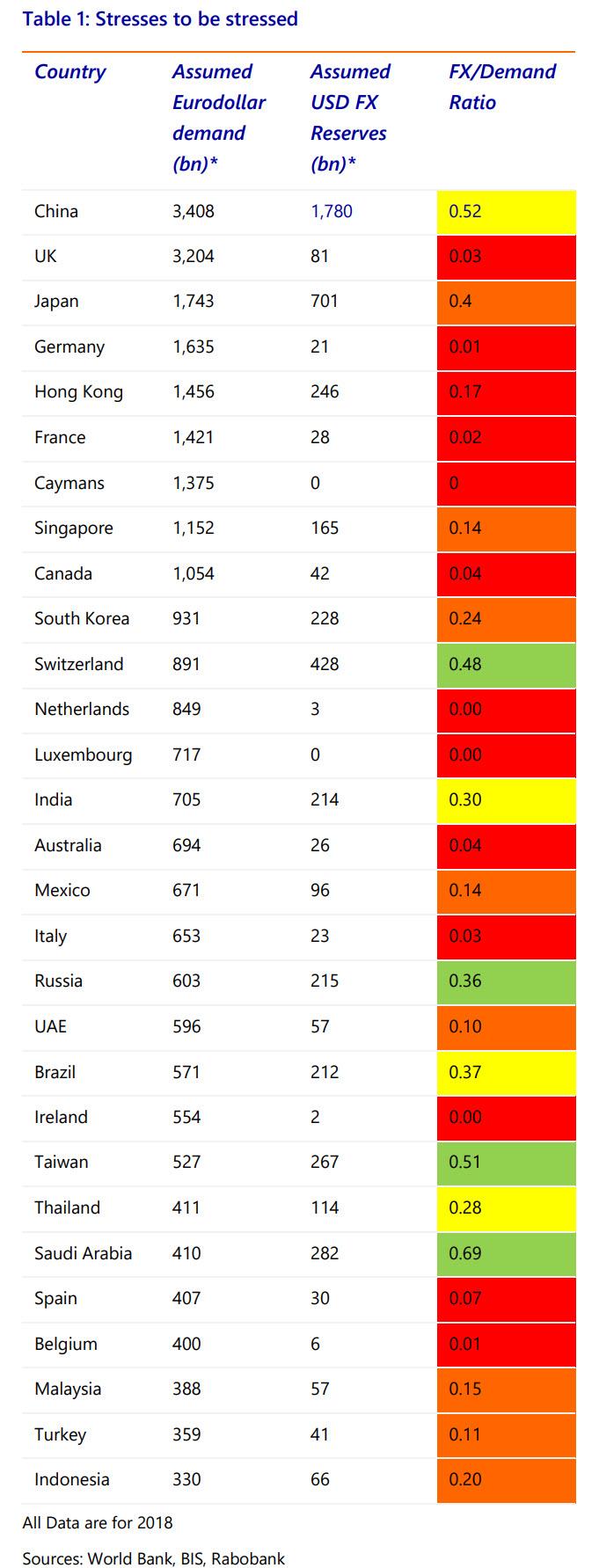

So, considering those systemic pressures, let’s look at where Eurodollar pressures are building most now. We will use World Bank projections for short-term USD financing plus concomitant USD current-account deficit requirements vs. specifically USD FX reserves, not general FX reserves accounted in USD, as calculated by looking at national USD reserves and adjusting for the USD’s share of the total global FX reserves basket (57% in 2018, for example). In some cases this will bias national results up or down, but these are in any case only indicative.

How to read these data about where the Eurodollar stresses lie in Table 1? Firstly, in terms of scale, Eurodollar problems lie with China, the UK, Japan, Hong Kong, the Cayman Islands, Singapore, Canada, and South Korea, Germany and France. Total short-term USD demand in the economies listed is USD28 trillion – around 130% of USD GDP. The size of liabilities the Fed would potentially have to cover in China is enormous at over USD3.4 trillion - should that prove politically acceptable to either side.

Outside of China, and most so in the Cayman Islands and the UK, Eurodollar claims are largely in the financial sector and fall on banks and shadow banks such as insurance companies and pension funds. This is obviously a clearer line of attack/defence for the Fed. Yet it still makes these economies vulnerable to swings in Eurodollar confidence - and reliant on the Fed.

Second, most developed countries apart from Switzerland have opted to hold almost no USD reserves at all. Their approach is that they are also reserve currencies, long-standing US allies, and so assume the Fed will always be willing to treat them as such with swap lines when needed. That assumption may be correct – but it comes with a geopolitical power-hierarchy price tag. (Think yet again of how Eurodollars started and the 1956 Suez Crisis ended.)

Third, most developing countries still do not hold enough USD for periods of Eurodollar liquidity stress, despite the painful lessons learned in 1997-98 and 2008-09. The only exception is Saudi Arabia, whose currency is pegged to the USD, although Taiwan, and Russia hold USD close to what would be required in an emergency. Despite years of FX reserve accumulation, at the cost of domestic consumption and a huge US trade deficit, Indonesia, Mexico, Malaysia, and Turkey are all still vulnerable to Eurodollar funding pressures. In short, there is an argument to save yet more USD – which will increase Eurodollar demand further.

We all become Agent Smith?

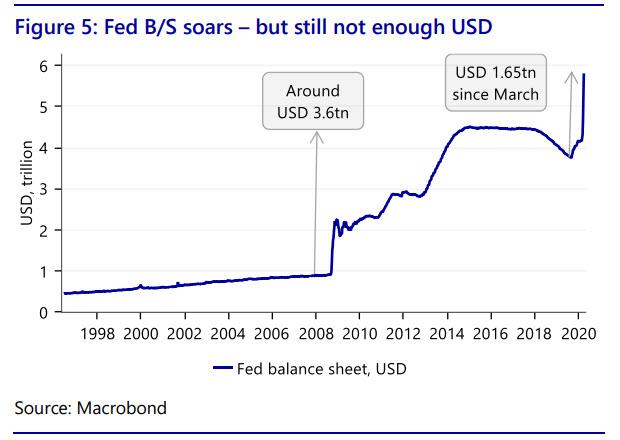

In short, the extent of demand for USD outside of the US is clear – and so far the Fed is responding. It has continued to expand its balance sheet to provide liquidity to the markets, and it has never done so at this pace before (Figure 5). In fact, in just a month the Fed has expanded its balance sheet by nearly 50% of the previous expansion observed during all three rounds of QE implemented after the Global Financial Crisis. Essentially we have seen nearly five years of QE1-3 in five weeks! And yet it isn’t enough.

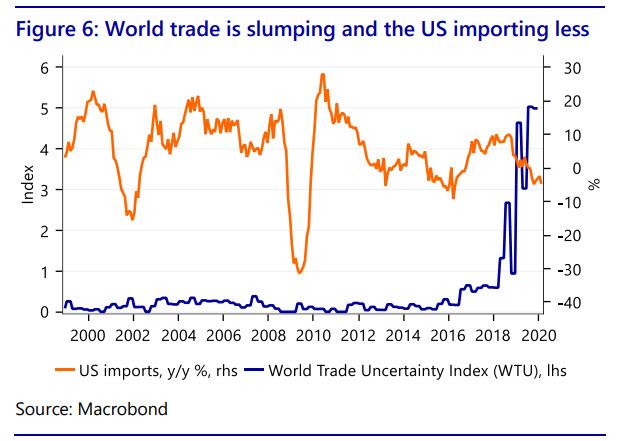

Moreover, things are getting worse, not better. The global economic impact of COVID-19 is only beginning but one thing is abundantly clear – global trade in goods and services is going to be hit very, very hard, and that US imports are going to tumble. This threatens one of the main USD liquidity channels into the Eurodollar system.

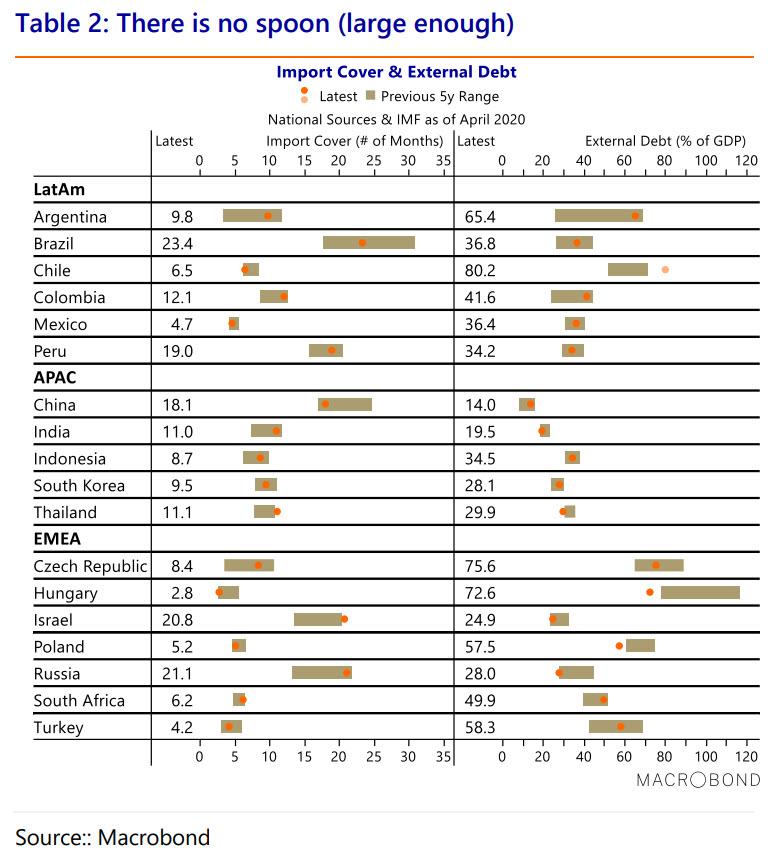

Table 2 above also underlines looming EM Eurodollar stress-points in terms of import cover, which will fall sharply as USD earnings collapse, and external debt service. The further to the left we see the latest point for import cover, and the further to the right we see it for external debt, the greater the potential problems ahead.

As such, the Fed is likely to find it needs to cover trillions more in Eurodollar liabilities (of what underlying quality?) coming due in the real global, not financial economy – which is exactly what the BIS are warning about. Yes, we are seeing such radical steps being taken by central banks in some Western countries, including in the US - but internationally too? Are we all to become ‘Agent Smith’?

If the Fed is to step up to this challenge and expand its balance sheet even further/faster, then the US economy will massively expand its external deficit to mirror it.

That is already happening. What was a USD1 trillion fiscal deficit before COVID-19, to the dismay of some, has expanded to USD3.2 trillion via a virus-fighting package: and when tax revenues collapse, it will be far larger. Add a further USD600bn phase three stimulus, and talk of a USD2 trillion phase four infrastructure program to try to jumpstart growth rather than just fight virus fires, and potentially we are talking about a fiscal deficit in the range of 20-25% of GDP. As we argued recently, that is a peak-WW2 level as this is also a world war of sorts.

On one hand, the Eurodollar market will happily snap up those trillions US Treasuries/USD – at least those they can access, because the Fed will be buying them too via QE. Indeed, for now bond yields are not rising and USD still is.

However, such fiscal action will prompt questions on how much the USD can be ‘debased’ before, like Agent Smith, it over-reaches and then implodes or explodes – the first of the logical endpoints for the Eurodollar system, if you recall. (Of course, other currencies are doing it too.)

Is Neo The One?

In conclusion, the origins of the Eurodollar Matrix are shrouded in mystery and intrigue – and yet are worth knowing. Its operations are invisible to most but control us in many ways – so are worth understanding. Moreover, it is a system under huge structural pressure – which we must now recognise.

It’s easy to ignore all these issues and just hope the Eurodollar Matrix remains the “You-Roll-Dollar” market – but can that be true indefinitely based just on one’s belief?

Is the Neo Coronavirus ‘The One’ that breaks it?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.