Over the past century, technological advancements have massively reduced the cost and time needed to create and circulate content. Though this has liberated artists, consumers are now drowning in a virtually infinite supply of things to watch, listen to and read. The answer to a world where attention is the key constraint, not capital or distribution, isn’t Big Media – it’s the Influencer Curator.

If you read a list of mankind’s most important or influential inventions, there’s not far you could go without coming across those of Thomas Edison. Oddly, however, it’s unlikely you’d ever see the device he so-routinely identified as his favorite: the phonograph. While it didn’t defeat disease, conquer the night skies or take flight, the phonograph was just as Promethean as vaccines, electricity and the Wright Brothers’ ‘Flyer’. For thousands of years, media was a privilege of the elite, concentrated in cities and confined to a single moment in time. With Edison’s phonograph, music had become non-rivalrous, infinitely replicable and indefinite. Yes, it took decades until the average family could afford a record player or radio, but the dawn of democratized consumption had arrived.

Unfortunately, however, this same trend led to an ossification in content creation and distribution. Records, after all, cost money. Production was expensive – as was distribution, marketing and promotion. So expensive, in fact, that almost every artist lacked the capital required to actually release their music – a need that paved the way for record labels (or TV studios, film studios, publishers etc.) that would finance said efforts in exchange for hefty royalty fees and content rights. These money men though wouldn’t and couldn’t afford to invest in every artist with a dream. Given the upfront cost of talent development and distribution, labels invested in “Arts & Repertoire” men, whose job it was to sift through countless musicians in order to identify the select few with “commercial viability”. Potential artists were then further cut down in number when it came time to actually distributing their content – and then again via marketing/promotional support. Underlying this fact was an unavoidable truth: content publishers had scale-related disincentives to support more than a handful of artists. Why record, distribute, market and promote 15 albums if you can achieve the same unit sales with 10?

Though this system was far from ideal, it was the inevitable outcome of a market in which talent was abundant, capital limited, distribution bandwidth (e.g. shelf-space, broadcast spectrum, print layouts) scarce, barriers high, and the cost of failure significant. But as a result, the content industry slowly shaped itself around a mysterious cabal of financiers and executive tastemakers that essentially programmed the national media identity. And anyone who wanted in had to move to New York, LA or Nashville, pay their dues and hope to work their way up until they could call the shots.

Of course, the music business was far from alone. The more expensive the medium, the more constrained the supply, the smaller the community and more homogenous the content. Local disc jockeys, newspapers and TV affiliates did have the opportunity to repackage and reprogram – to imprint their personality or take, if you will – but this was limited in scope, drew upon only the content that was already distributed, had to fit within an existing corporate identity and, again, depended on access to capital or infrastructure.

Over time, however, technology did what it does best: production costs fell, quality went up and distribution bandwidth increased. Economics, in turn, improved, as did the industry’s carrying capacity – the number of artists, titles, and pieces of content that could be supported. The media business was beginning to loosen up.

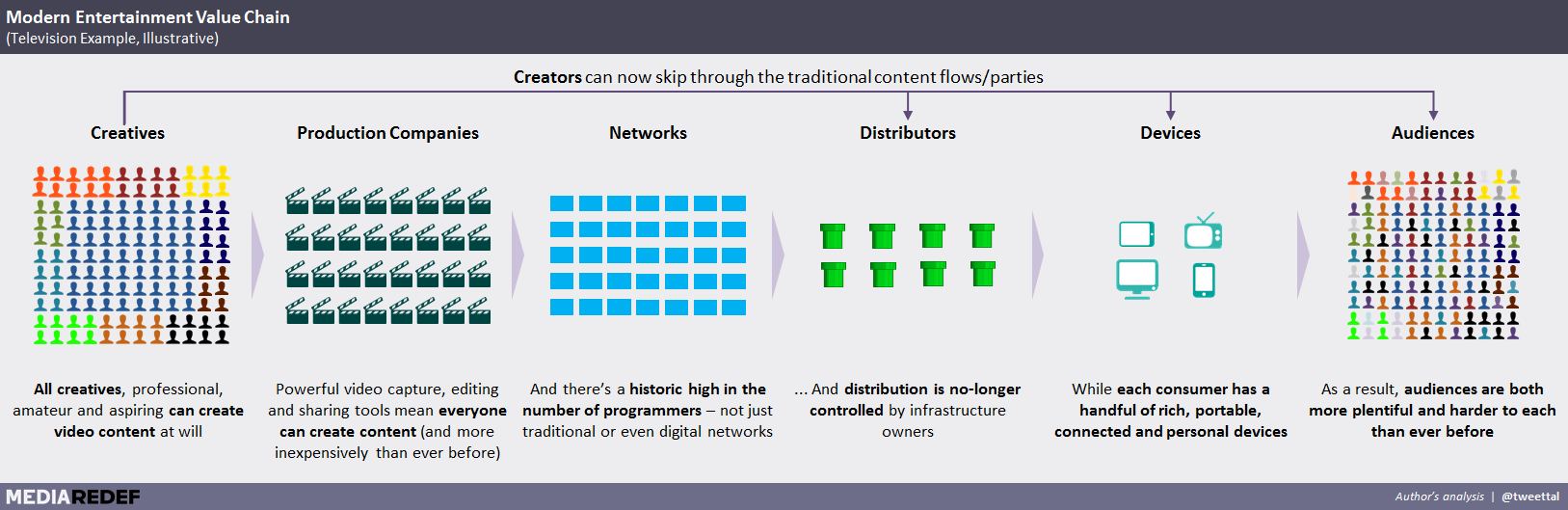

But it took until the late 2000s – more than a century after the phonograph – for creation and distribution to truly democratize. With the Internet, distribution became free and truly non-rival (if a bit non-excludable), while the proliferation of low-cost media equipment, mobile devices, and powerful editing software dramatically lowered the costs of production. The rise of creator-based consumption platforms and crowd-funding platforms, meanwhile, eliminated many of the remaining barriers hindering independent content creation. This meant that content could not only be created by those outside the business, but that commercializing this content became significantly less expensive and risky. This led to a massive increase in available, indexed and distributed content.

While the media business benefited from many of these changes, the consequences have been fundamentally destabilizing. The television industry has experienced such a surge in original content that annual cancellation rates have quintupled over the past 15 years (twice as many original scripted series were cancelled last year than even aired in 2000). Since 1985, the indie film industry has seen a nearly twentyfold increase in the number of theatrical releases even though ticket sales have remained flat (in 2014, the Head of SXSW’s film festival decried that “the impulse to make a film had far outrun the impulse to go out and watch one”). Plummeting music sales and unprecedented competition have made launching a new artist so expensive that catalogue sales now make up more than 200% of major label profits (in 2014, David Goldberg privately encouraged Sony Entertainment CEO Michael Lynton to essentially halt A&R efforts, as well as investments in actually making new music). With the democratization of media creation, it’s easier than ever to make content but harder than ever to make a hit.

Ironically, the increasing difficulty in creating hits has not bolstered the “hit maker” system but rather further weakened it instead. In 2013, Macklemore became the first unsigned artist since 1994 to have a number-one single in the United States – a feat he repeated just three months later. Mega-star Taylor Swift has been with an independent label since her debut album and multi-platinum groups such as The Eagles and Radiohead have left the majors to start their own. The struggles of print publishing are well-known, but the uniqueness of some of “print’s” recent successes are worth mentioning. The 50 Shades of Grey trilogy, which has outsold The Harry Potter septet on Amazon in the United Kingdom and made author E.L. James 2012’s highest-earning author, became a viral hit on FanFiction.net long before it was picked up in print (and it’s unlikely a publisher would have bought the rights upfront). Andy Weir’s The Martian is another self-publishing success story.

This metamorphosis is about far more than ever increasing amounts of content and a handful of stars existing outside the traditional media ecosystem. The entire media value chain is inverting. For decades, scarce capital and constrained distribution capacity meant that the media’s industry bottlenecks sat in the middle of the value chain. Today, however, the bottleneck has moved to the very end: consumer attention. This shifts the balance of power from determining what should be made to finding a way to convince people what to watch, listen to or read in a world of infinitely abundant content.

The preeminence of this challenge has given to the rise of a new type of aggregator-distributor, including news content sites like Gawker, the Huffington Post and BuzzFeed; video and music aggregation services like Netflix, YouTube and Pandora; and even physical products subscription offerings like Birchbox and Lootcrate. What’s more, it enabled the major social networks to use their customer data to build massive stickiness, launch their own publishing platforms and become traffic kingmakers. More broadly, this shift has swung the balance of power from programmers with the ability to greenlight content to curators with the ability to get that content heard, seen or read. Of course, the old programming and financing guard remain important, but with the democratization of production and the explosion of content creation, the power of 1st party programming is quickly being eclipsed by the ascendance of 3rd party content curation. The gatekeepers are still manning their posts, but the city outgrew the walls and the barbarians circumvented the gates entirely.

The Tastemaker Curator

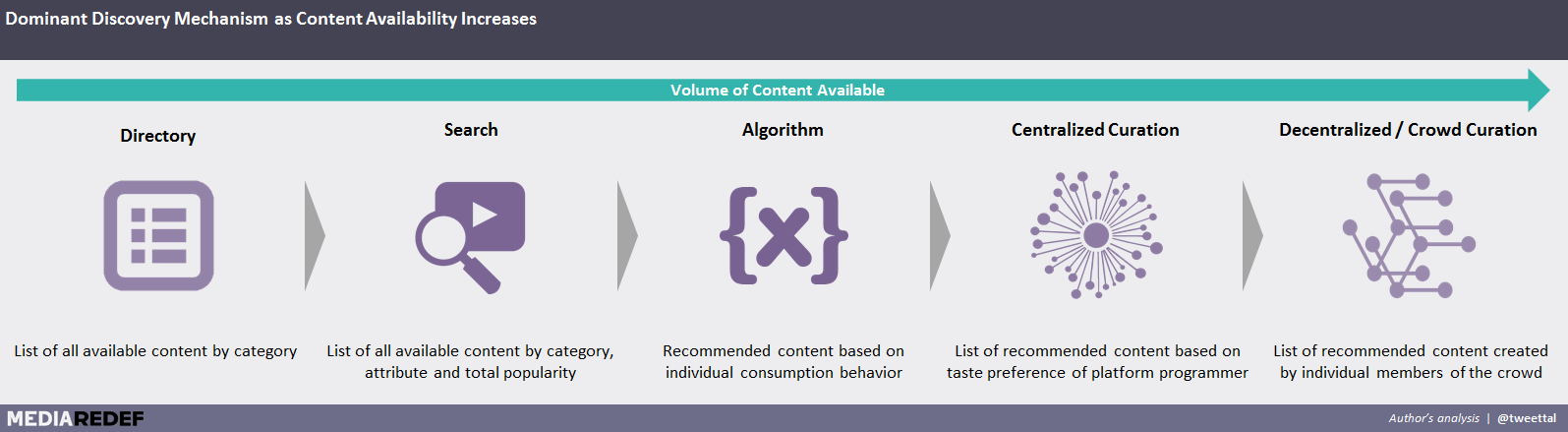

To date, curation has primarily been delivered in three ways. Most common is algorithmic recommendation powered by behavioral and social graph data – e.g. Facebook’s newsfeed, Spotify’s Discover Weekly, Netflix’s content feeds. Second is hand-picked selections delivered by and through the major distribution platforms – e.g. Twitter Moments, Snapchat stories and Beats Radio 1. Third are one-off recommendations and shares by individual users – posting a Spotify playlist, reblogging a tumblr post, sharing a link or retweeting a tweet. Suffice to say, curation today is dominated by well-capitalized technology-media companies and supported by significant manpower and bandwidth.

However, the next evolution in the media value chain will be the rise of decentralized curation – with individual tastemakers building up mass followings and driving enormous consumption by recommending various articles, videos, shows, films, albums, exhibits and so on. While there’s no way to effectively do this at scale today, the transition is long in development. Almost everyone today remixes content they’ve created with 3rd party content (just look at any social feed), reviews and engages in media commentary (ditto) and uses the recommendations of others to decide what to watch, see, listen to or even believe. Similarly, every social graph includes a handful of node users whose endorsements proliferate across the social web. The formalization of this influence will therefore represent both a natural and value-add extension of existing user behavior.

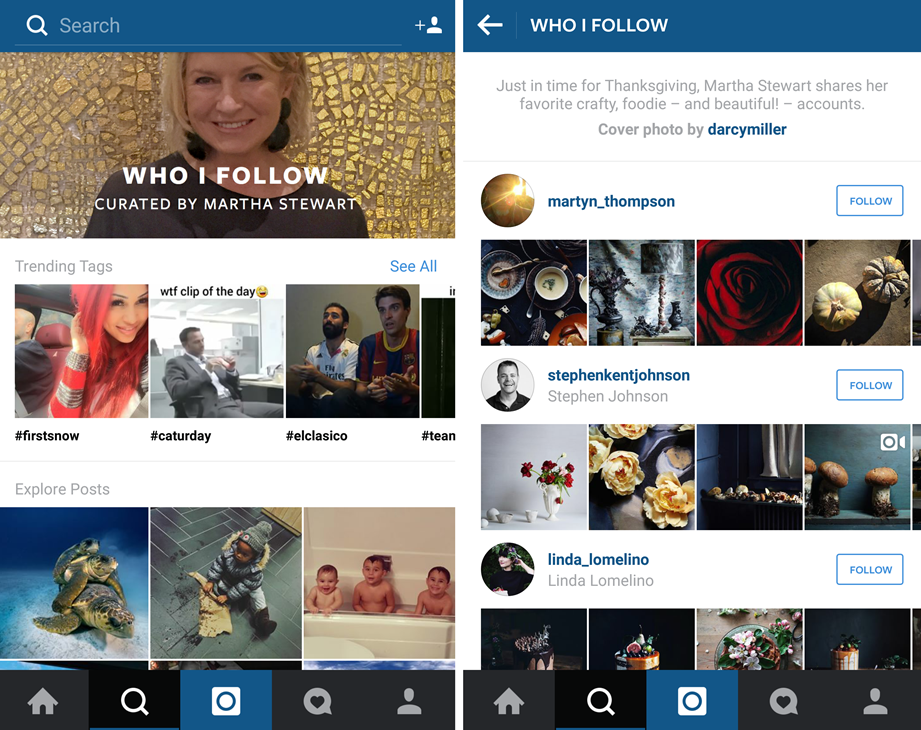

To this end, multimedia curation is and will continue to be pioneered by today’s web influencers: YouTube, Instagram and Twitter celebrities such as Connor Franta or Michelle Phan that have already developed, personal and authentic voices that transcend individual verticals, genres and brands and influence millions. But it is not and will not be confined to these digital influencers alone. “Traditional” celebrities that connect with their audiences on a deep level – a Howard Stern, Taylor Swift, Glenn Beck or Kardashian – are positioned to and in some cases already beginning to dive into curation. Mindy Kaling doesn’t have 6M Twitter followers, two books and her own TV show just because she’s funny, but because her taste, endorsements and perspective resonates.

The template already exists: Martha Stewart and Oprah both built extensive, multi-category empires in the pre-digital era largely based on the power of their stamp of approval. With new distribution technologies, the influencers of today, and maybe Martha herself, will be able to build even more comprehensive empires than ever before, all built on the power of their taste and delivered via inexpensive but massively distributed web infrastructure.

This ability for consumers to tap into specific voices will also be critical as more content and more users come online. Consumer time (or “attention”) doesn’t scale with either the volume or ready availability of content at their disposal. Discovery functions, too, have a maximum. The significance of 1,000 likes, 400 ratings or 3.2M plays is very different with 3B Internet users than it was with 500M. Not only does contextualizing these social cues become impossible, but the demographics of the reviewers continues to change – first in terms of age and income, then geography and culture – making it difficult to understand the personal validity of any crowd based metric. That’s not to say that a product on Amazon with 1,400 reviews and a 3.8 star rating isn’t good – just that the common review mechanisms found across the web mathematically soften taste out to the average. This works a lot of the time, but we tend to have very particular tastes in certain categories – and there is a certain staleness created by narrowing these averages down using look-a-like groups and other algorithmic techniques. Not to mention the fact, that such an approach often lacks the element of serendipity and surprise from discovering something you loved but didn’t expect (especially if you would otherwise have avoided it). As a result, curators both solve a media painpoint and enrich consumption.

Where Will this Be Built?

The most likely enablers of the age of curation will be today’s social platforms. Though rarely viewed as such, these companies – Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Instagram – are already in the business of content creation, remixing and distribution. As such, the expansion from one-off filters, albums, shares and vlogs to curation would represent an organic evolution of their existing user toolset. More importantly, however, this change will be critical if these platforms want to continue to grow user engagement and manage the massive influx of user created and user-submitted content.

Many services have invested in centrally-managed human curation feeds in recent months – such as Snapchat’s Live Stories or Instagram’s event and theme-based “Explore” collections – but these can only scale so far without the help of the crowd or truly massive content investments (just ask Encyclopedia Britannica). Twitter, notably, is already planning changes that will enable brands and everyday users to create their own moments and Instagram has been promoting curated follower lists from top influencers on the platform for months now. Others are likely to follow.

To support this, Facebook, Twitter and company will require a broad set of new user tools and capabilities – such as the ability to bundle multiple types of on-and-off platform content, create evergreen collections, offer paid subscriptions and connect to physical goods fulfillment. Buy buttons are just the beginning. As a result, we may even see a new type of social platform emerge.

However, curation-centric services won’t just be served by the social giants; there are already a number of in-market players today. Music start-up Dash Radio, for example, enables tastemakers to create their own OTT radio stations – free from the need to be “advertiser friendly”, FCC compliant or audience-maximizing – and has accumulated three million US monthly users to date. Meanwhile Spot, an app out of Expa, recently launched with the goal of providing the means for people, experts and influencers to rate and recommend their favorite restaurants and other locations. In some cases, curators will have their own dedicated apps – case in point, the massive success of the Kardashian clan’s apps (particularly Kylie’s), which are in effect vehicles for the families to curate both content and products including clothing, music and other media.

Influencer Inc.

As these capabilities become more available throughout the social web and individual curators grow into the power of their voices, many will expand beyond simple curation and commentary. Brand extensions, licensing partnerships and hired staff will be commonplace – just look at Bethany Mota’s massive Aeropostale partnership to catch a glimpse. The most successful curators will even begin commissioning content themselves. In many ways, the programmer-to-curator shift will appear to come full-circle. But the distinction is critical.

Traditional creatives (though talented) gained cultural influence through their connection to insiders and access to capital. Today’s curators are influential because they have relationships with audiences. They’re hired by fans because of their taste, not hired by executives to satiate the appetites of fans. This, when combined with frictionless commerce and fan engagement channels, can also make these influencers far more wide-reaching and multi-vertical than even the Oprahs and Martha Stewarts of the past. As such, their influence in taste making is an inversion of the classic model, not merely the replacement of old tastemakers with new.

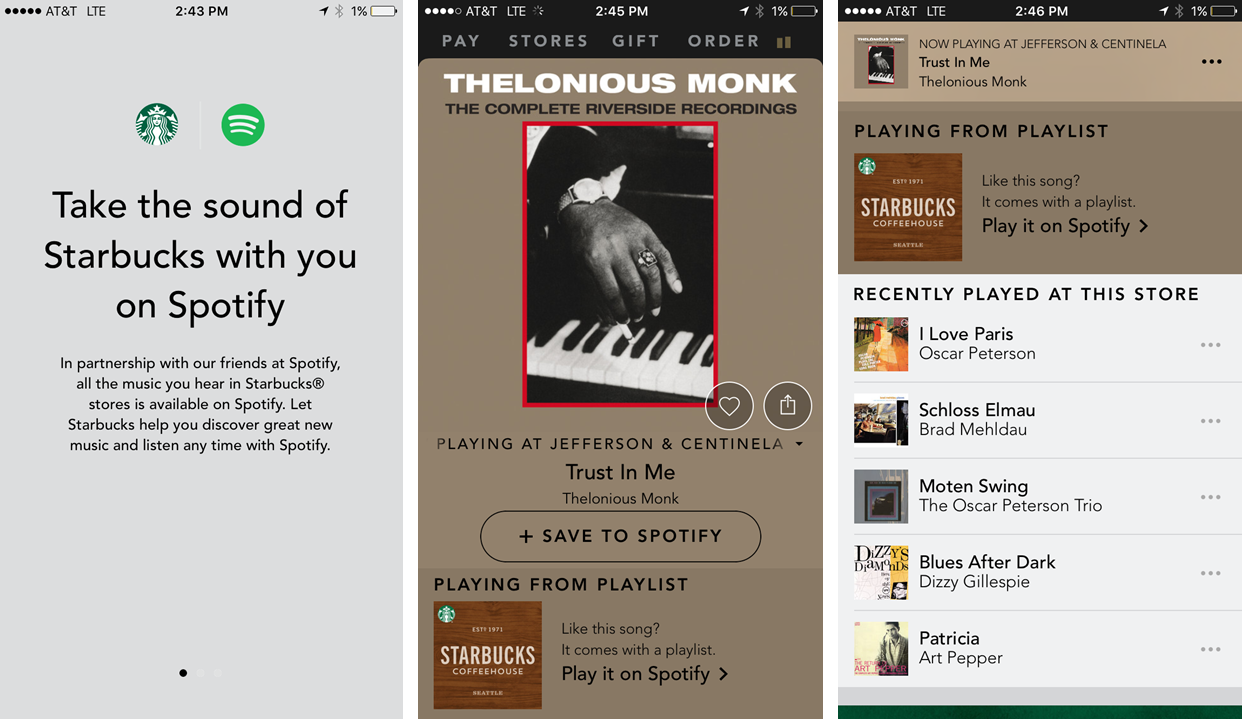

For this same reason, many non-media brands will embrace curation in the hopes of strengthening their own consumer relationships and establishing a distinct voice in the age of social marketing. The first movers here are likely to be brands that have already achieved large footprints across multiple social networks, emphasize lifestyle rather than just their products, and interact with their customers several times a week (if not more than once a day) – RedBull, GoPro, Starbucks, and Soulcycle are just some of many potential curator-brands. It’s not hard to imagine any or all of them operating their own Twitter Moments, Snapchat live stories or newsletter services as part of their apps and loyalty programs, not merely as marketing efforts but as integral parts of their consumer offerings. This shift is in already process at Starbucks. Users can now listen to the company’s music playlists right from their loyalty application and add their favorite tracks to their Spotify account.

Programmers and Programming in a Curation World

As curation’s role in both content discovery and consumption intensifies, content companies will not only see their programming advantage continue to erode, they’ll also need to change much of their existing beliefs, norms and business models. For most curators (and audiences), the distinction between content type (e.g. art, music, film, TV) and class (“premium”, “low-grade”, “UGC”) is without value. They curate according to their voice and interests, not library categorizations. This, of course, will prove prohibitive for Big Media. Few will want to acknowledge the competitiveness of “less valuable” content (this claim has been at the core of pitches to marketers and ad agencies, after all), let alone subject themselves to risk of unmanaged content adjacency (“what if the next recommendation doesn’t align with our brand?!”). As a result, most content creators will initially resist influencer-based distribution, though its growing importance as a channel will make this retreat only temporary. If Mindy Kaling “owns” your target audience, you’ve few options other than to distribute through and with her.

More progressive content owners, however, will create technology and release strategies specific to influencer-based audience acquisition. Publishers, for example, already enable socially referred traffic to slip through paywalls – a model that should be extended to other media categories such as music, podcast, film and television. In addition, we’re likely to see subscription add-ons that allow curators to provide their followers with an opportunity to consume content from directly inside a curated environment. More simply, some content owners will look beyond distributing advance copies to journalists and include key curator-influencers. To promote its artificial intelligence original series, for example, AMC should have sent screeners to the likes of Elon Musk (who boasts 3M Twitter followers and often warns of the dangers of AI) and Marc Andreessen (who has 450k followers and vehemently rejects AI alarmism).

Regardless, traditional players will struggle to flex their cost structures, organizational models and incentives for the curation era. Few curators will see the need to purchase content licenses or commit to minimum guarantees. As a result, the monetization of curator-distributed content will tend towards revenue shares and branded content – neither of which mesh well with Hollywood today. What’s more, Tinseltown is already struggling with fragmented audience data, complex release windows and unpredictable ARPU.

Open Source Content

Six years ago, Simon Cowell was asked to explain his gift for identifying musical talent. While his answer seems reductive, its simplicity explains why the shift from programming to curation is so significant: “I have average tastes. If you looked in my collection of DVDs, you’d see Jaws and Star Wars. In the book library, you’d see John Grisham and Sidney Sheldon. And if you look in my fridge, it’s children’s food — chips, milkshakes, yogurt.” For nearly a hundred years, mass market programming was an essential capability in the media business. Content creation and distribution were too expensive and failure fraught. But that doesn’t mean that our cultural tastes were some sort of objective standard alongside universal truths such as the equality of man or “thou shalt not kill”. They were defined and constrained by legions of Simon Cowells – white, high income men with common backgrounds and a shared idea of what was or should be listened to, watched or read.

In the decades since the phonograph was invented, technological changes have enabled our tastes to expand, our artists to diversify and our content to swell in abundance. While the notional shift from programming to curation can feel academic, it represents a crucial step in the democratization of media. Through thousands of individual curators, each of us will be able to escape the tyranny of averages and the limitations of algorithmic recommendations, as well as benefit from the ability to become tastemakers ourselves. For once, if we can’t find something good to watch, read, or listen to, we will have no one to blame but ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.