The experts were wrong again. Even on the day of the referendum, traders and oddsmakers, pollsters and professors were forecasting a vote to remain in the European Union.

In the wake of a stunning decision to leave the 28-nation bloc, the nation is left divided in a way not seen since the 1980s. What was a very British question over a lukewarm relationship with Europe turned into accusations of lying, evocations of Hitler and rather un-British slurs. The government -- whatever its complexion -- will now have to nurse those wounds.

The recriminations were stilled for a moment last week after the killing of lawmaker Jo Cox but the passions unleashed by months of bickering and assertions on the economy and immigration have yet to play out.

“Jo understood that rhetoric has consequences,” Stephen Kinnock, who shared an office with Cox in the U.K. Parliament at Westminster, told lawmakers on Monday after they were recalled for tributes. “When insecurity, fear and anger are used to light a fuse, then an explosion is inevitable.”

Who to Believe?

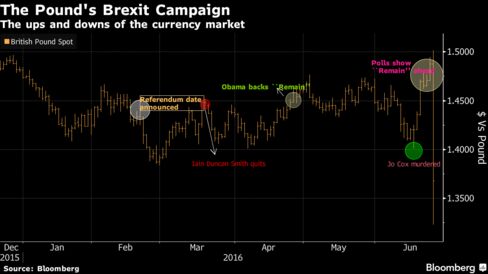

The battle at first didn’t quite grip the nation as much as it did financial markets, the pound gyrating with every twist and turn. Then it became a case of who to believe. Would Britain be better off forging its own trade agreements? What is sovereignty anyway? Is Turkey really about to join the EU? Do immigrants cost more to public services than they provide in labor?

“I hope we remember it as the high-water mark and the end of post-truth politics,” said Drew Scott, a professor of European Union studies at Edinburgh University. “The campaign has been riven with half-truths and falsehoods on both sides. We don’t seem to worry about the truth anymore -- it’s just about winning or losing.”

Cameron delivers a statement on Feb. 20.

It was a referendum that Cameron promised to call to keep his Conservatives together and see off the threat of Nigel Farage’s U.K. Independence Party at last year’s election. First, he had to hammer out a new agreement with the EU, including restricting welfare payments for migrants from the bloc.

Cameron summoned his cabinet for its first meeting on a Saturday since the 1982 Falklands war. On Feb. 20, they voted to back his deal and hold the referendum on June 23. It was never going to be enough for the Euroskeptics; cabinet ministers immediately started taking sides.

Enter Boris

Justice Secretary Michael Gove, one of Cameron’s closest friends and allies, appeared in a photo in front of a “Vote Leave” banner along with Iain Duncan Smith, the minister in charge of work and pensions.

Johnson speaks to reporters at his home, Feb. 21.

But the first real piece of choreography was in front of a crowd of reporters at the home of Boris Johnson, Cameron’s former Oxford University pal and biggest political threat. He declared “after a huge amount of heartache” he would go against the prime minister. The prize asset for the “Leave” campaign, bookmakers also put the now-former London Mayor as the front-runner to succeed Cameron. The pound had its worst day since 2010.

In response, Cameron launched a verbal assault on Johnson in the House of Commons, suggesting that he had based the decision on his ambition to replace him. Cameron, who had called for a civilized campaign, surprised lawmakers with the vehemence of his attack. Less than two weeks later Duncan Smith said Cameron’s “scaremongering” was damaging his integrity.

His campaign has “become characterized by spin, smears and threats,” Smith, a former Conservative leader, wrote in the anti-EU Daily Mail. He resigned from the cabinet on March 18 over the budget as Cameron returned from a regular EU summit in Brussels. The tone of the campaign was set.

Carney’s Eyes

From then on, every intervention was dismissed by one side or another as trying to spook the public, whether Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne’s warning of decades of economic pain, or the concerns of International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde and Bank of England Governor Mark Carney.

Mark Carney and Christine Lagarde

In the first of testy exchanges with politicians, pro-Brexit lawmaker Jacob Rees-Mogg told Carney in March “it is beneath the dignity of the BOE to be making speculative pro-EU statements.” Carney, often more statesman than banker in recent weeks, replied: “I’m not going to let that stand.”

U.S. President Barack Obama, on a trip to London to mark the Queen’s birthday, backed membership of the EU and said the country would be “at the back of the queue” for negotiating a trade deal with the U.S. In an article in the pro-Brexit Sun newspaper, Farage repeated a claim previously made by Johnson that Obama’s Kenyan background meant he was predisposed to dislike the British.

There were also alliances, some more unlikely than others. Old Labour Party leaders and chancellors shared platforms with Conservatives, pro-EU former Prime Minister John Major campaigning with his successor, Tony Blair.

Hitler Jibes

While the number of undecided voters could have always swung it one way or the other, opinion polls showed little sign of a revolution. In May, Sadiq Khan, an advocate of staying in the EU, defeated pro-Brexit candidate Zac Goldsmith to succeed Johnson as mayor.

Johnson left to tour Britain on Vote Leave’s battle bus, and Cameron looked more and more confident that things would go his way. Struggling on the economy, Vote Leaveput the focus back onto immigration, claiming that Turkey was close to joining the EU.

Johnson said the EU shared Adolf Hitler’s goal of unifying Europe, admittedly by different means. Other “Leave” campaigners mocked up German Chancellor Angela Merkel as Hitler. EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said Johnson needed to be re-educated about Brussels.

“The only redeeming feature of Cameron is the other side are even worse,” former Scottish leader Alex Salmond, who fought and lost the 2014 independence referendum on whether to leave the U.K., said this week. “It’s been a poisonous, appalling campaign.”

‘Court Jester’

Major called it “squalid.” He likened Johnson to a “court jester,” albeit what turned out to be milder than Energy Secretary Amber Rudd’s comment days later that he “was not the man you want driving you home at the end of the evening.”

But the strategy was working. A YouGov Plc poll on June 1 showed the sides were now neck and neck, while the bookmakers increased the probability of Brexit to above 20 percent. The pound started weakening again.

In Brussels, the mood swung from frustration that the interests of one country were dominating the EU agenda, to confidence that the U.K. would never vote to leave. Then, in the two or three weeks before the vote, there was the sudden fear that the unthinkable might actually happen.

Top officials in the European Commission held daily meetings. Privately, some began to express the opinion that Cameron was not handling the campaign as well as they had hoped and that Farage and Johnson were being allowed to dictate the debate.

Merkel’s Moment

In a highly unusual intervention, Merkel took a pre-arranged question from a BBC reporter in English to warn the U.K. of isolation.

Angela Merkel

“For those coming from the outside, and we’ve had lots of negotiations with third-party countries, we would never make the same compromises, or achieve the same good results, for states that don’t take on the responsibility and costs of the single market,” she told reporters in Berlin.

The currency market reflected the anxiety increasingly being felt in the pro-EU camp. In the first week of June, the pound sank after a YouGov survey showed “Leave” at 45 percent and “Remain” at 41 percent.

Rattled, Cameron held an unscheduled press conference on a rooftop overlooking the river Thames. His alarm was clear the moment he started speaking, denouncing Johnson and Gove and accusing them of lying to the public.

“The Leave campaign are resorting to total untruths to con people into taking a leap in the dark,” Cameron said on June 7. “It’s not for me to say why they’ve made these factual errors and mistakes, but it is for me to call it out.” Later in the day, Cameron and Farage faced questions from a live television audience. Farage claimed the “Leave” campaign was being bullied: “We’re British, we’re better than that,” he said.

Tory on Tory

A week later, Conservative lawmaker Sarah Wollaston quit the "Leave" campaign over the claim it would free up 350 million pounds ($524 million) a week for the National Health Service. “They have knowingly placed a financial lie at the heart of their campaign,” she said.

Cameron realized he needed the Labour Party to detract from the Conservative in-fighting. Extracts of a speech by Osborne were held back so as not to clash with a one by former Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown, whose intervention was key in the final run-up to the Scottish independence referendum.

Rather than throw the campaign into reverse, five opinion polls in 24 hours gave “Leave” the lead and Rupert Murdoch’s Sun newspaper backed the drive to leave the EU. “I’m sensing real momentum for “Leave” around the country,” Farage said on Twitter. “We can win this and get our country back!”

Final Days

Then everything changed.

A flotilla of fishing boats led by Farage sailed up the Thames to be met by rock musician Bob Geldof haranguing them through a sound system and playing themed music as small boats carrying “in” banners buzzed around. Fishermen started hosing the “Remain” boats.

’In’ and ’Leave’ boats on the Thames on June 15.

One contained Brendan Cox and his children the day before his wife and their mother was fatally shot and stabbed on a street near Leeds. The man charged with her murder later gave his name in court as “death to traitors, freedom for Britain.”

All sides suspended campaigning for the weekend. Farage talked of how the Leave campaign was running away with it: “We did have momentum until this terrible tragedy,” he said.

When the news of Cox’s murder broke during an EU finance ministers’ meeting in Luxembourg, shock was accompanied, for some, by the belief that it may help the “Remain” camp. In the run-up to the debate, several EU officials pondered whether a major event -- a terrorist atrocity or a huge influx of migrants -- would swing the outcome. Was this the defining moment?

The pound gained, ultimately touching $1.50 for the first time this year. Betting shops shorted the odds of a Brexit win. Endorsements came from household names for remaining in the bloc, from former soccer star David Beckham to TV presenter Jeremy Clarkson.

Little could still the furies.

On June 21, the day before his wife would have turned 42, Brendan Cox said in a BBC interview that Jo had become concerned about the “tone of the debate.” The worry was that it was “whipping up fear and whipping up hatred potentially,” he said. “The EU referendum has created a more heightened environment for it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.