China’s banks converted more than 1 trillion yuan (US$149.2 billion) of debt into stock holdings in more than 70 state-owned enterprises, in the government’s largest debt-to-equity swap effort to bail out the country’s most indebted borrowers, according to the official China New Agency, citing a notice by the state planning department.

The scheme, signed between Chinese banks and companies in the steel, coal, chemicals and equipment manufacturing industries, has helped to lower the aggregate debt ratio in these industries, the agency reported, citing the National Development & Reform Commission (NDRC).

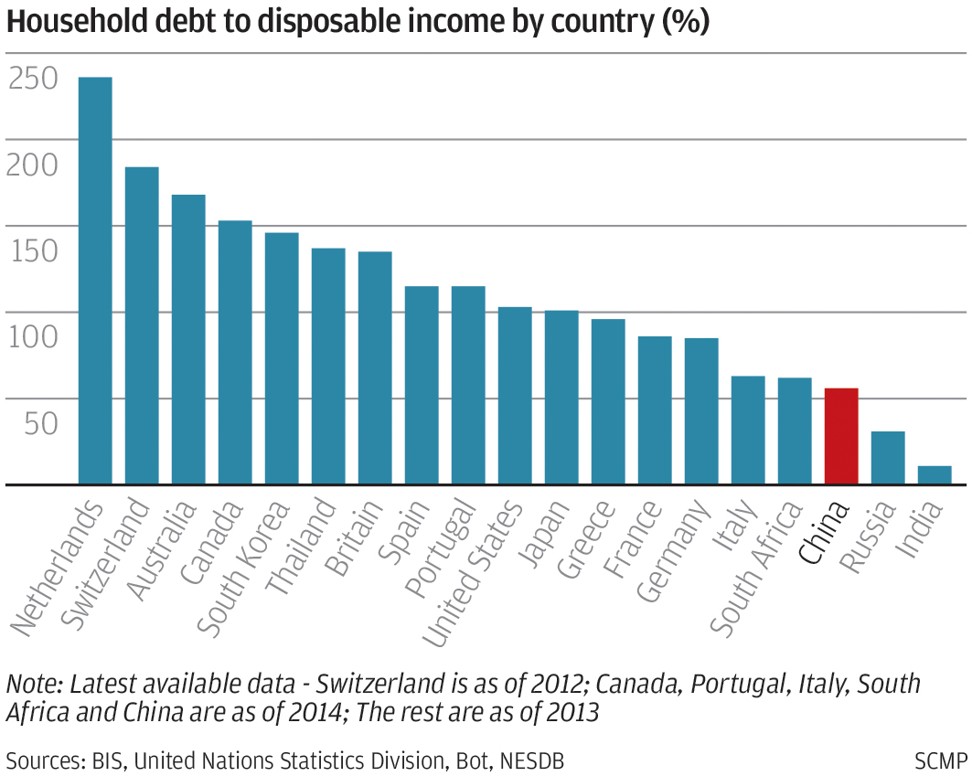

China’s 2016 corporate debt soared to about 170 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), from 100 per cent in 2008, according to the Bank of International Settlements. At double the average of other economies, the aggregate debt of China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private companies stood at US$15.7 trillion last year.

The government is anxious to reduce the debt owned by the moribund state sector to shield the country’s financial system from the risks of defaults, while the economy’s growth pace slows.

The idea of swapping banks’ debts into equity holdings was raised by China’s Premier Li Keqiang during the National People’s Congress in March last year. It wasn’t a new idea. The scheme was used during the 1990s to clean up the books of China’s state banks.

What’s different this time is the debt-to-equity swap would proceed under market principles, giving banks and financial institutions a bigger say in choosing the indebted companies whose borrowings were to be swapped, and in fixing the financial terms of the swaps. This was done to avoid channelling funds into so-called zombie companies that were inefficient and destined for bankruptcy.

Still, the swaps were complicated by a set of draft rules released by the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) a day before the NDRC announcement, which left more questions than answers regarding the details of the exchange.

“The scheme had been unrolling since last year, and we are concerned about what the new rules mean to the existing deals,” said Chen Shujin, chief financial analyst at Huatai Financial.

For example, some banks have channelled fund they raised through wealth management products from retail investors into the debt-to-equity swap programmes. It isn’t immediately clear whether that practice is allowed under the CBRC’s latest draft rules, Chen said.

Investors are keen to know more details, including how the shareholding structure of the target company will be changed, and the risk weightings brought by the investment for banks, she added.

The largest shareholder, which holds more than 50 per cent stake in a debt-to-equity swap unit should be a locally incorporated commercial bank. Other qualified shareholders (non-bank financial institutions) include less than 42 brokers, around 20 insurance firms, and some trust firms, according to the draft rules.

“According to the latest draft rules, banks will hold more than 50 per cent stake of the unit that handles the swap, which means they will have a bigger say for the projects,” said ING Bank NV’s economist Iris Pang. “That’s a good sign. It partly eases the concern of the market that banks would be under pressure from local governments if they are just minority stake holders.”

Improving corporate leverage has helped China’s bond defaults to slow in 2017, according to a report by Goldman Sachs.

Based on industrial profits, earnings improvements are spreading further downstream, relieving the corporates’ debt stress, it said.

“The median level gross debt-to-EBITDA, a measure of profitability, fell to 2.1 times at the end of 2016, the first reduction after five years of increases, while net debt-to-EBITDA fell to -0.2 times,” the report said.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.