American and European banks stay more at home. Chinese ones extend their reach

IN THE 1980s, when Citicorp was America’s largest bank and pursuing every avenue for international expansion, John Reed, the bank’s boss, would muse about moving its headquarters to a neutral location, notably the moon. Such sentiments are inconceivable today. Jamie Dimon, boss of JPMorgan Chase, Citi’s successor atop the league tables, recently said he is an American “patriot” first, head of a bank second. His strategy, though hardly shunning international markets, reflects this.

Mr Dimon turned down several big foreign acquisitions before and during the financial crisis. His stellar reputation may rest as much on those undone deals as on those completed. Citi, meanwhile, has been lopping off foreign affiliates. It has retail operations in just 19 countries, down from 50 in 2007. Further contraction may be in the offing. Bank of America has long chosen to live down to its name, as an almost entirely domestic bank.

The same process is under way in western Europe. Visible retrenchments by leading banks in each country reflect even deeper ones that are harder to see. On August 22nd McKinsey, a consultancy, released a trove of statistics showing how the map of global banking has changed over the past ten years. According to its analysis of the leading banks in each country, foreign claims (including loans, guarantees, etc) have contracted by a third for Swiss and British institutions and by half for those in the rest of Europe. Even the volume of foreign-exchange trading, after a long history of expansion, is falling.

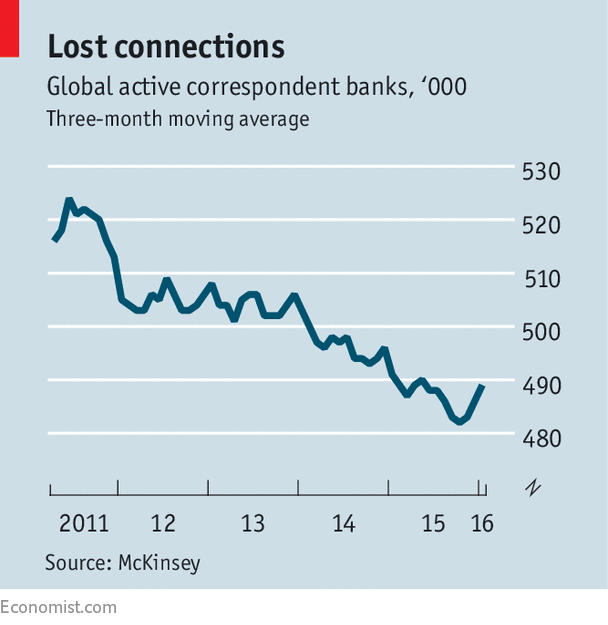

The downward trend is particularly sharp, and significant, in “correspondent” banking, traditionally seen as the first level of financial support for world trade (see chart). The correspondent ties between banks in different countries have mattered particularly for companies in places without global banks that can finance imports and exports. The number of correspondent relationships has been declining since 2011, according to McKinsey.

Why this has occurred is no mystery. Correspondent relationships used to be seen as a responsible way for a bank to transact business in a country it did not know well. It has become a source of vulnerability: a bank may be held accountable for any transaction even if only as a link in a long chain. The rising cost of complying with regulations on money-laundering, economic sanctions and terrorism-financing has had the predictable consequence of prompting a broad pullback.

Harder to understand is work by the Bank of England and America’s National Bureau of Economic Research, showing a long-term correlation between growth in capital requirements and declines in cross-border lending. McKinsey notes that rules passed to ensure liquidity, particularly in a crisis, may be easier to satisfy if money is close to home.

American and European retrenchment has been partially offset by expansion elsewhere. Canadian banks, which sailed through the financial crisis, now have half their assets offshore, up from 38% a decade ago. Chinese banks, having had negligible foreign assets a decade ago, now have more than $1trn. Strong domestic growth means that this sum is still just a tiny fraction of their balance-sheets. Banks in Japan, India and Russia are also expanding internationally at a strong pace.

This geographic shift could continue for many years to come. Similar trends, however, have been seen in the past only to go abruptly into reverse. The Chinese government has recently signalled its concern at some Chinese firms’ foreign acquisitions, suggesting there may be problems percolating. Whether Western banks stir from their recent quiescence may also depend on the regulators. Over correspondent banking, for example, there is a debate in government. The State Department wants America’s banks to bring other countries, especially poor ones, into the global financial system. The Treasury, focused on checking untoward activity and holding banks to account, is more cautious. Banks would like to stay out of the crossfire.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.