That’s bad news for a government hoping for a windfall

ON NOVEMBER 8th 2016, Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, stunned its 1.3bn people by announcing that most banknotes would soon become worthless. Indians then queued for weeks on end to exchange or deposit their banned money at banks. The comfort for the poor was that the greedy, tax-dodging rich would suffer more, as they struggled to launder their suitcases full of cash by year-end.

Not so. A report from the central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), on August 30th suggests that of the 15.4trn rupees ($241bn) withdrawn—roughly 86% of all banknotes by value—15.3trn rupees, or 99% of them, have been accounted for. Either the “black money” never existed or, more likely, the hoarders found a way of making it legitimate.

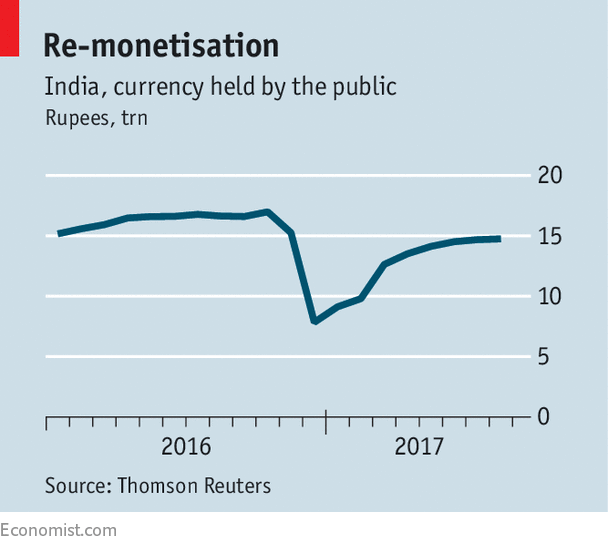

Defenders of the scheme say it is merely one plank of a wider fight against informal economic activity and corruption. Banks have enjoyed an influx of cash. Digital payments are up (from a low base), as issuance of replacement notes has not caught up with the pre-withdrawal peak (see chart).

Officials once privately salivated in hope that maybe a quarter of the money, if not more, would remain in the shadows. An edict to the central-bank governor to renege on his promise to “pay the bearer” of unreturned, demonetised notes fuelled social-media rumours that this could finance a one-off dividend to be dished out to all Indians.

In fact, not much more than 100 rupees a person is available. The RBI has released the figure only now, claiming, improbably, that it needed to count the cash in its tills. Its reputation for independence and competence has been dented. So has national pride: demonetisation has pared growth and handed back to China India’s coveted crown of being world’s fastest-growing large economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.