I’M GONNA make a $hit t$n of money on August 2nd on the Stox.com ICO.” Written in July on Instagram, these words made Floyd Mayweather, a boxer, the first big celebrity to endorse an “initial coin offering”, a form of crowdfunding that issues cryptographic coins, or “tokens”. Stox, an online prediction market, went on to raise more than $30m, some of which seems to have gone directly into Mr Mayweather’s pocket. Other VIPs, including Paris Hilton, a socialite, followed suit and endorsed ICOs. But this source of easy cash may now be drying up: on November 1st America’s Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) warned that such promotions may be unlawful, if celebrities fail to disclose what they receive in return.

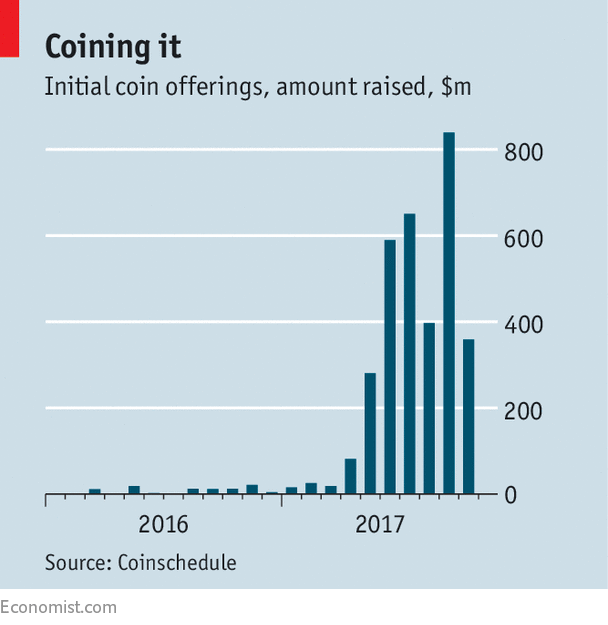

The endorsements and the SEC’s attempt to rein them in are the latest episodes of token mania. Virtually unknown a year ago, ICOs are now more celebrated than initial public offerings (IPOs), the conventional way of floating a firm. Over the past 12 months $3.3bn has been raised in more than 200 ICOs, according to Coinschedule, a data provider—compared with only about $70m in the same period a year ago. This surge is one reason for the boom in bitcoin, a crypto-currency, which was worth around $7,500 on November 2nd. As Benjamin Lawsky, a former securities regulator in New York, put it recently: “Regulators have never seen a new financial product explode with the speed and velocity [of ICOs].”

Unsurprisingly, supervisors have stepped in. China and South Korea, where ICOs had become part of the local gambling culture, have already outlawed them. Many regulators in Western countries have by now made clear that they consider at least some of the coins (or “tokens”) that are distributed in an ICO to be securities, which need to be regulated as such, with all that this entails in disclosure and other requirements. Leading the pack, the SEC said in a report on the DAO, an ill-fated early ICO, that offerings of this kind need to be registered (or apply for an exemption). But big regulatory problems remain unsolved.

The most pressing open question is what a token really represents, says Peter van Valkenburgh of Coin Centre, a think-tank. Technically, the answer is straightforward, at least for those familiar with crypto-currencies. Tokens are mostly entries on Ethereum, a “blockchain”, or “distributed ledger”, copies of which live on many connected computers around the world—much like the one that underlies bitcoin. The Ethereum ledger, however, not only keeps track of a currency, called “ether”, but hosts what are known as “smart contracts”, programs that encode business rules. Investors send ether to an ICO’s smart contract, which generates tokens that can be traded. The ICO’s issuer can keep the ether, and use the funds to develop its project.

Legally, things are more complicated, says Kevin Werbach of Wharton, a business school at the University of Pennsylvania. The SEC, for instance, argues that the technology is irrelevant: when tokens are used to raise funds, they are securities. By contrast, champions of ICOs hold that, although they are initially used to raise funds, they also often have a function in the projects they finance and hence should be treated differently. In Filecoin, an online market for digital storage that raised a record $257m, the tokens will be used to pay or get paid for space on disk drives.

Tokens of affection

Most issuers will have a hard time convincing the SEC and other regulators that theirs is a “utility token”. For many existing firms, such as Kik, a messaging app, which raised nearly $100m, raising funds seems the priority. For other issuers the problem is that the tokens they are selling are for projects that exist only on paper, and so have no other function than to bring in money. And most investors currently buy tokens not for their utility, but because they are betting that their value will rocket.

To avoid the heaviest regulation, issuers are keeping the lawyers busy. One increasingly popular legal construct in America is called SAFT (“Simple Agreement for Future Tokens”)—in effect, options to buy tokens, rather than tokens themselves, thus dodging the problem posed by projects that do not yet use the tokens. As raising money gets harder, marketing becomes more important. One result is the “pre-sale”, in which early investors often get a big discount to help boost demand for the ICO.

A second big open question is where tokens will fit into the regulatory landscape. Being pieces of code, they can take on the form of any financial product. “They collapse all asset classes into one,” says Lex Sokolin of Autonomous Research, a consultancy. This will cause legal friction, particularly in America, where different asset classes are regulated by different agencies.

Other jurisdictions are easier to navigate. Many crypto firms are based in Zug, Switzerland, where they can save taxes and tokens are less likely to be considered securities. In January a “distributed-ledger technology framework” will go into effect in Gibraltar (although it does not specifically address ICOs). A big unknown is China which, despite its ICO ban, is clearly interested in all things crypto, as long as it can control them.

And third, there is the question of how the organisations financed by ICOs will be governed. Finding robust solutions is vital: many of these entities see themselves as a new type of firm. The idea is that because founders, employees and users all hold tokens, their incentives are aligned: all have an interest in expanding their network, which will drive up the tokens’ value. These organisations will be “decentralised”, meaning that no single group will be in charge, and they will be managed, at least partially, by smart contracts to keep them on track.

Making all this work will be hard, as shown by the case of Tezos, which raised $232m to finance the development of another blockchain. Its version will come with a sophisticated governance mechanism to avoid the problems that beset bitcoin, which in August split in two when developers and firms that cryptographically mint (“mine”) the currency disagreed on the way forward. (A further “fork” was just called off.) Holders of Tezos tokens will get a vote commensurate with their holdings or be able to delegate it to someone else.

Ironically, though, Tezos is the first substantial token-financed organisation that has run into serious governance problems. The founders opted for a complex legal structure, which involves a Swiss foundation that controls the proceeds of the ICO. They are now embroiled in a public quarrel with the head of this foundation over how it should be run. Moreover, the founders and others involved are being sued by an ICO contributor for alleged breaches of securities law, which Tezos denies.

Tezos’s travails, as well as the general token mania, have pushed some issuers to rethink. Blockstack, whose ICO started on November 13th, did without a pre-sale, instead giving users a discount. It turned itself into a “public-benefit corporation”, obliged to pursue the public good as well as profit. The firm, which has also said it has not raised more than $110m, has a lofty ambition: to develop software and services to bring the internet, now dominated by a few tech giants, back to its decentralised roots. If Blockstack runs into trouble, too, the very concept of distributed organisations may be at risk.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.