The labour market is the healthiest it has been for at least a decade. But inflation remains low

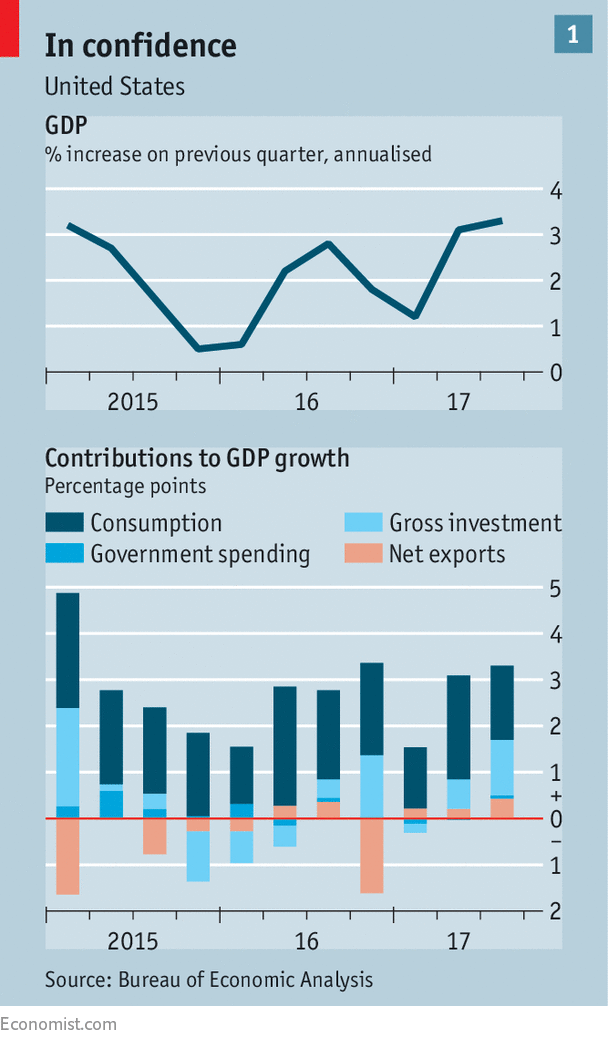

USUALLY politicians pretend that good economic news on their watch is no surprise. But America’s recent growth figures have been so positive that even the administration of President Donald Trump has allowed itself to marvel. “It’s actually happening faster than we expected,” mused Mick Mulvaney, the White House budget chief, in September, after growth rose to 3.1% in the second quarter. (Mr Trump in fact came to office promising 4% growth, but the goal now seems to be 3%.) Mr Mulvaney warned that hurricanes would soon bring growth back down. Instead, in the third quarter, it rose to 3.3%—a figure celebrated with more conviction. The administration’s initial caution was wise: quarterly growth figures are volatile, and few economists expect growth above 3% to carry on for long. Yet there is no denying that the economy is in rude health.

In part, that reflects the strength of the global economy. But it is also the culmination of a years-long trend. As politics has consumed America’s attention for the past two years, common complaints from earlier in the decade have, one by one, begun to look dated. The median household income is no longer stagnant, having grown by 5.2% in 2015 and 3.2% in 2016, after adjusting for inflation. During those two years, poorer households gained more, on average, than richer ones. Business investment is no longer tepid: it drove growth in the third quarter of the year (see chart 1). Jobs are plentiful—unemployment is just 4.1%. From Wall Street to Main Street, businesses ooze confidence. What is more, tax cuts are poised to stimulate the economy. Analysts no longer ask when growth will at last pick up. Instead, they wonder if the economy might overheat.

The Federal Reserve is alert to the risk. On December 13th it announced its third interest-rate rise this year, and the fifth during this economic expansion, taking rates to 1.25-1.5%. The median forecast of the Fed’s rate-setting committee is for three more rate rises in 2018. Not a single rate-setter thinks that today’s low rate of unemployment is sustainable. Yet all predict that joblessness will fall further in 2018.

The Fed is right to fret. Credible forecasters are almost unanimous: the sustainable rate of growth, as America’s population greys, is closer to 2% than to 3%, whatever Mr Trump says. In the past three months the economy has created an average of 170,000 jobs per month. Yet over the decade to 2026 the population of 20-64-year-olds will, on official projections, grow by fewer than 50,000 a month. Joblessness cannot fall for ever, so, unless productivity accelerates, growth must fall. If the Fed keeps money too loose, inflation will eventually rise, as the economy gets too hot.

Households seem exuberant. In October the University of Michigan’s consumer-sentiment index hit its highest level since 2004. Recent consumption growth has been fuelled by a steep fall in household saving, which is down from over 6% of GDP two years ago to just 3.2% today. In early 2016 some analysts fretted that consumers were squirrelling away the money they were saving on cheap petrol, and so denying the economy a needed fillip. Today, the opposite worry seems more pertinent: oil prices have recovered somewhat, but the saving rate has tumbled.

Falling saving is a worry, but consumers’ cheer is well-rooted in the buoyancy of the labour market and the strength of household balance-sheets. With interest rates low, debt-service costs, as a share of after-tax income, are close to a record low. Most American mortgages bear fixed interest rates, so homeowners are shielded from higher rates. And house prices have been rising, too. In the third quarter of 2016 they passed their peak of 2007. Since then, they have risen by another 6.3%.

Rich pickings

Higher house prices and a stockmarket boom have delivered a wealth windfall. Households and non-profit organisations now hold assets worth nearly seven times their after-tax income, the highest ratio on record. Middle-earners have seen the biggest gains, according to a recent Fed survey. The average net worth of households in the middle quintile of the income distribution (ie, from the 40th to the 60th percentile) rose by 34% between 2013 and 2016. House prices have recovered despite strict lending regulations introduced after the financial crisis. Mortgages remain difficult for those with poor credit scores.

Politics has helped business confidence. Optimism surged among small firms after Mr Trump won the election. On December 5th, days after the Republicans’ tax bill passed in the Senate, confidence among chief executives reached its highest level for nearly six years, says Business Roundtable, a lobby group. The prospect of a big cut to corporate taxes (and, perhaps, of deregulation) has boosted a stockmarket already on a long winning run. From the market trough in March 2009 to Mr Trump’s election, the S&P 500 rose at an average annual pace of 16%. Since his victory, it has grown at a 22% annualised pace.

A booming stockmarket pleases investors, but it poses another conundrum for the Fed. Some rate-setters worry that loose monetary policy may inflate asset bubbles. And soaring stocks have contributed to a general loosening of financial conditions. The dollar is about 7% weaker, on a trade-weighted basis, than it was at the start of the year. Long-term bond yields have also fallen slightly, having surged after the election. William Dudley, president of the New York Fed, has argued that looser financial conditions strengthen the case for interest-rate rises, because it is by influencing financial markets that monetary policy is supposed to work. According to analysis by Goldman Sachs, financial conditions have actually eased after every instance of Fed tightening since it started raising rates in December 2015.

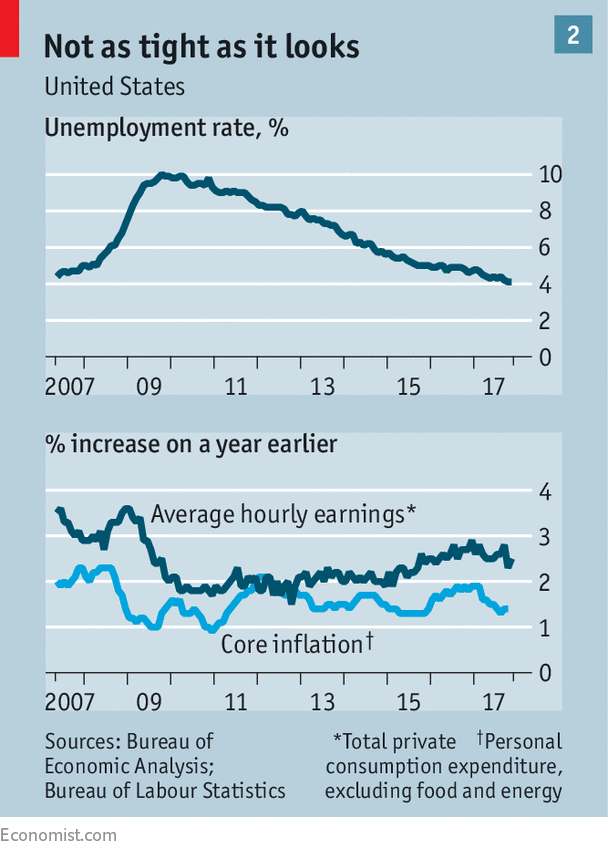

A crucial element is missing, however, from the “overheating” analysis: inflation. Since the spring, it has persistently fallen short of expectations. Excluding food and energy, prices in October were only 1.4% higher than a year earlier, by the Fed’s preferred measure. Wages, too, do not reflect the apparent strength of the labour market (see chart 2). Though blue-collar and service workers are seeing higher pay rises—the wages and salaries of production workers grew at a 3.8% annualised pace in the third quarter of the year—professionals have seen their pay growth slow. Overall, wages are rising by about 2.5%, no faster than two years ago.

One reason is the time it takes for low unemployment to translate into inflation. In the meantime, one-off factors can distort the data. Ms Yellen points to price cuts for mobile-phone contracts at the start of the year. These should soon drop out of the numbers. Others blame the “Amazon effect”—brutal price wars among retailers. Perhaps, too, the Phillips curve—the relationship between inflation and unemployment—is jagged, and inflation will suddenly spike once joblessness falls too low.

Or perhaps the labour market is not as hot as the Fed thinks. Estimates of the so called “natural” rate of unemployment—the rate consistent with no upward or downward pressure on inflation—are notoriously unreliable. Rate-setters have gradually revised theirs down, from over 5% at the end of 2013 to 4.6% today. Persistent low inflation may force them to repeat the trick. In any case, notes Michael Pearce of Capital Economics, a consultancy, the Fed’s surveys suggest the labour market is not as tight as it was in, say, mid-2000, when unemployment fell as low at 3.8%. Even in that expansion, underlying inflation did not hit 2%. The boom ended not because of an inflationary surge, but because the dotcom bubble burst.

Moreover, unemployment is not the only variable to watch. It does not count those who are not looking for a job. During and after the crisis, Americans left the workforce in droves. But since late 2015 the labour-force participation of working-age people, especially women, has been rising. For much of 2016, this trend kept unemployment fairly flat even as the economy added jobs aplenty. Though unemployment has fallen in 2017, working-age participation has kept on rising.

Sceptics doubt whether participation is tightly linked to the economic cycle. They point out that some trends, such as falling participation among working-age men, are very long-running. But participation is at least tricky to forecast. Its recent growth has defied official projections produced by the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS).

Whether that continues will set the economy’s speed limit. The Economist has calculated that, if participation in every age and sex demographic group continues on its trend from the past year, the labour force will grow by around 135,000 workers a month. At recent rates of job growth, unemployment would fall to 3.8% by the end of 2018. But should participation revert to the long-term trend forecast by the BLS, only 86,000 new workers will appear each month. Unemployment would fall much faster next year, to 3.4%.

The Fed’s rate rises will probably slow job growth before these hypotheses can be tested. Frustrated doves think the central bank should probe the boundaries of the labour market, and not assume it knows them in advance. It risks denying workers the first truly tight labour market in over a decade. Moreover, only if wage growth is allowed to rise will firms be pressed to invest more in labour-saving technology. This could raise productivity growth, revealing more hidden capacity. (Rising investment and a hint of a productivity rebound this year suggest such a process may be about to kick off.) And if the Fed tightens too quickly, sparking a recession, it may be hard to reverse course, since interest rates cannot fall far before hitting zero.

As evidence that rate-setters are fretting needlessly about inflation, doves point to the bond market. That long-term bond yields have fallen even as the Fed has raised rates suggests investors think the risk of inflation is shrinking. Ms Yellen’s retort is that inflation expectations, as measured by surveys, have held steady this year. That suggests something else could be pushing bond yields around.

Soon a new Fed chairman will be confronting these puzzles. Jerome Powell is to succeed Ms Yellen in February. Mr Powell, who has served as a Fed governor since 2012, has broadly supported Ms Yellen’s strategy of gradual rises in interest rates. In a confirmation hearing before a Senate panel on November 28th, he seemed, if anything, a little more doveish, acknowledging that low labour-force participation among working-age men might indicate remaining slack in the labour market.

Yet the Fed committee is turning over rapidly, and Mr Powell may find himself surrounded by hawks. An example is Marvin Goodfriend, whom Mr Trump has nominated to fill one vacant seat. Mr Goodfriend has for years called for higher rates, prematurely sounding the alarm about inflation as early as 2010. In 2012 he described as “doubtful” the notion that the Fed could bring unemployment down to 7%. When Ms Yellen departs, Mr Trump will have another three seats to fill. Moreover, voting rights rotate among regional Fed presidents, whom the president does not pick. Three doves—Charles Evans from Chicago, Neel Kashkari from Minneapolis, and Robert Kaplan from Dallas—will lose their votes in January, to be replaced by more hawkish voices. A fourth dove, Mr Dudley, plans to retire in 2018. His new colleagues may test Mr Powell’s commitment to continuing Ms Yellen’s approach.

The Fed must also decide how to respond to Mr Trump’s tax cuts. Even if the economy is not on the edge of overheating, these are poorly timed. Were stimulus warranted now, the Fed could always cut rates, avoiding the higher public debt that fiscal stimulus incurs. Tax cuts might spur some investment and raise growth by a few tenths of a percentage point in the short term. But they are also likely to nudge the Fed towards faster rate rises. The central bank’s economic model suggests that for every 1% of GDP in tax cuts, rates will eventually rise by 0.4 percentage points. The bill that passed the Senate on December 2nd would raise deficits by 0.2% of GDP in 2018 and 1.1% of GDP in 2019, not counting its effect on work and investment incentives.

Policymakers in recent years have tended to show too much caution, rather than too little. That is why a full recovery from the financial crisis has taken so long; it is in part why inflation is too low today. It seems likelier that they will err on the side of caution than allow the economy to run too hot. But America’s policy debate is finely poised. As the economy approaches its capacity, the margin for error shrinks.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.