Currencies and stockmarkets have tumbled, though growth rates are solid

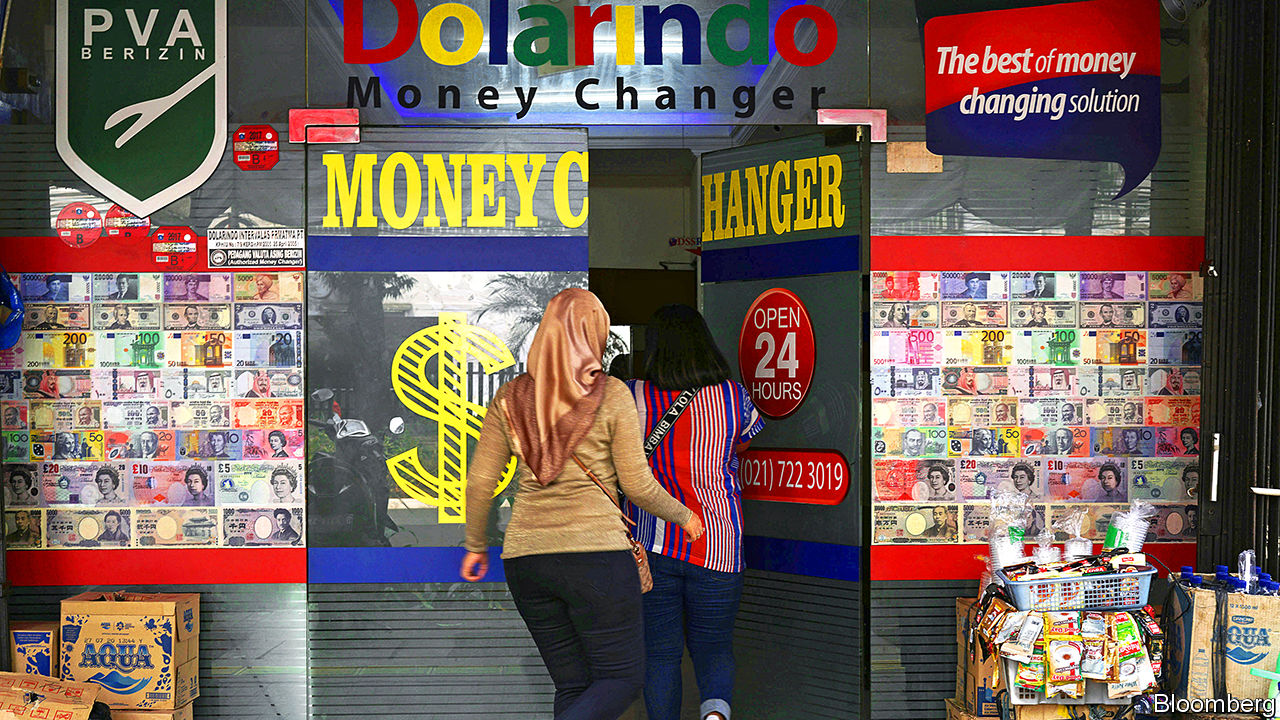

THERE are many ways to defend a currency. Ayam Geprek Juara, an Indonesian restaurant chain that serves crushed fried chicken, has offered free meals this month to customers who can show they have sold dollars for rupiah that day. The restaurant has provided more than 80 meals to these “rupiah warriors”, according to Reuters, a news agency.

Perhaps it should extend the offer to the staff of Bank Indonesia, the country’s central bank, which is only about 20 minutes away from one of the restaurant’s branches. To defend the rupiah, it has been selling billions of dollars of foreign-currency reserves, which have fallen from over $125bn in January to less than $112bn in August. Despite these sales, and four interest-rate rises since May, the rupiah has lost almost 10% of its value against the dollar this year, returning to levels last seen during the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98.

India’s rupee has fared even worse, reaching a record low against the dollar. And even where Asia’s currencies have remained steady, its stockmarkets have faltered. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index fell by 20% from late January to September 12th, meeting one definition of a “bear market”. Mainland China’s markets are struggling.

A person returning from Mars would assume that something horrible had happened in the region, says Chris Wood of CLSA, a brokerage. But in fact Asia’s emerging economies are enjoying a happy spell of respectable growth and stable consumer prices. Only Pakistan has a combined trade and fiscal deficit as devilish as Turkey’s or Argentina’s. And not even Pakistan has anything like their double-digit rates of inflation. India’s GDP grew by over 8% last quarter, compared with a year earlier. Indonesia’s expanded by over 5% (as it almost always does). And China’s grew by over 6% (as it always does). Nor is a widespread slowdown expected this quarter.

The trade war has soured the mood in China and Hong Kong. But China’s exports to America still grew by over 13% in August, and the Canton trade fair was at its busiest for six years, according to the Institute of International Finance, an industry group. Many American customers are obviously keen to shop before the broader tariffs take effect. Some of China’s neighbours, especially Vietnam, believe they can win the trade war by taking in its refugees: the manufacturers that move out of China to escape tariffs.

India and Indonesia are largely insulated from the trade war, thanks to the strength of their domestic demand. But that same strength leaves them exposed to two other dangers—the higher oil price and America’s remorseless monetary tightening. India’s oil-import bill for the past five months was more than 50% higher than a year ago. Its current-account deficit could widen to 3% of GDP this fiscal year (which ends in March), according to some forecasts. Indonesia’s could expand similarly.

These gaps would be easy to finance if foreign investors were in an indulgent mood. But they are not. As American interest rates have risen, emerging markets have looked less rewarding and more dangerous by comparison.

In response India’s government is tweaking taxes and regulations to attract more foreign capital and fewer foreign goods. It will, for example, suspend a tax on rupee-denominated “masala” bonds sold outside India. It has also decided to curb imports of inessential items, without yet specifying what those may be.

In Indonesia the government is encouraging state firms to dilute imported fuel with biodiesel, extracted from local palm oil. It has delayed big infrastructure projects. And it has increased import tariffs on over 1,000 goods, including perfume, stuffed toys and tomato ketchup. The life of a rupiah warrior is not without sacrifices.

In theory, such ad hoc measures should be redundant in two economies that have embraced flexible exchange rates. If the trade deficit is unsustainable, a floating currency is supposed to weaken, thereby discouraging imports (and encouraging exports) automatically. By this logic, the declining rupee and rupiah will eventually resolve the problem they reflect.

But Indonesia worries that its foreign-currency debts will be harder to sustain with a weaker rupiah. These debts amount to about 28% of GDP, far below Turkey’s and Argentina’s totals, but are still too large to ignore. Moreover, about 40% of its rupiah-denominated government bonds are held by foreigners, according to Joseph Incalcaterra of HSBC, a bank. That “presents a sizeable outflow risk,” he says, which is one reason why Indonesia’s central bank has raised interest rates faster than India’s.

Both countries also worry that falls in the currency will beget further falls. After fighting the rupiah’s slide in 2013, Chatib Basri, Indonesia’s finance minister at the time, argued that a sharp drop in the currency would have revived memories of the crisis in 1997 and led to investor panic.

That wobble in 2013 followed some stray remarks from America’s Federal Reserve, which suggested it might soon slow its asset purchases. The subsequent spike in Treasury yields caused turmoil in emerging markets and threatened America’s fragile recovery, prompting the Fed to clarify and soften its position. The more recent increase in Treasury yields is different. It reflects a robust American expansion, reinforced by generous corporate-tax cuts. This time, there is little reason to expect a rethink at the Fed. America does not feel emerging markets’ pain.

Asia has long dreamed of “decoupling” from America so it can prosper even when the world’s biggest market does not. Instead, it is suffering even when America is not. And partly because America is not.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.