OVER the past few weeks whispered advice has circulated among frequent flyers in India. Do not book any tickets in advance with Jet Airways, the country’s second-largest airline; it might not be long for this world. The suspicions had a grain of truth. On August 9th the carrier took the extraordinary step of delaying the planned release of its results for the three months to June. On August 27th it delivered the bad news—it lost $189m in the quarter, compared with a small profit in the same period of last year. It wants to raise capital to avoid running out of cash.

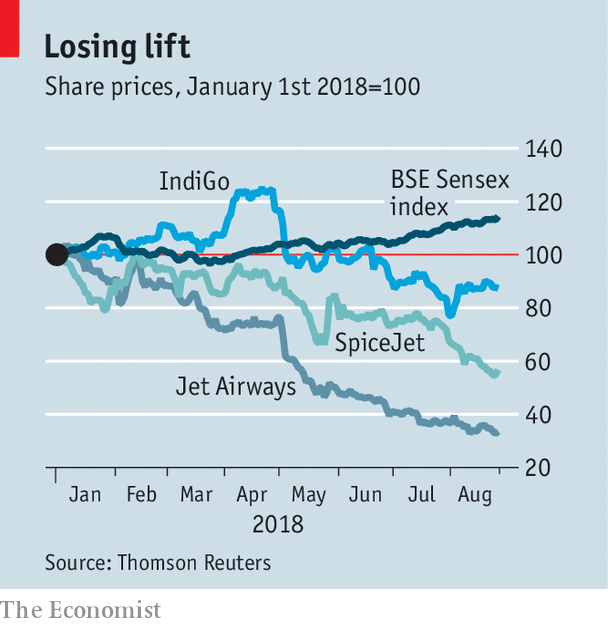

Jet Air is not the only Indian carrier to stall this summer. Airlines stocks have fallen even as Indian shares have performed decently overall (see chart). On August 14th SpiceJet, India’s fourth-largest carrier, announced a surprise loss of $5m in the second quarter. A month earlier IndiGo, India’s largest airline, posted a 97% year-on-year decline in net profits for the same period. And in June the government abandoned its planned privatisation of Air India, the flag carrier which has lost money for a decade and is saddled with $7.8bn in debt, after it attracted no bidders.

At first glance, the Indian aviation market should be booming. Domestic “revenue passenger kilometres”, a measure of bums on seats, grew by 18% in the year to June. IATA, a trade body, forecasts that by 2025 India will be the world’s third-largest aviation market. What has crippled airline profits this year are rising costs and flat fares, explains Rahul Kapoor of Bloomberg Intelligence, a research firm.

The price of jet fuel has surged in tandem with that of oil (up from $26 a barrel in 2016 to over $70). IndiGo’s fuel bill rose by 54.4% in the three months to June, compared with last year. Making matters worse, since January the dollar, the currency in which fuel is priced, has strengthened by a tenth against the rupee, the currency in which ticket revenues are booked.

Despite higher oil prices, IATA expects airlines globally to make $33.8bn in profit this year. Many carriers hedge against swings in fuel prices and exchange rates to ensure sudden spikes do not bankrupt them, says Mark Martin, an aviation consultant based in Dubai. But airlines in India did not do this. Poor corporate governance is likely to be responsible.

In another departure from industry norms, Indian airlines have not been able to pass those higher fuel costs on to flyers by raising fares. Indian travellers are “the world’s most price-sensitive”, says Mr Kapoor. If fares rise, they take the train instead—or stay at home. Whereas low-cost Western carriers, such as Ryanair and Southwest, recoup what they lose on discounted fares with offsetting fees for checked-in luggage and extra legroom, Indian passengers simply forgo the extras.

The Indian government does not help airline profits either, says Robert Mann, a former airline executive. India has Asia’s highest aviation-fuel taxes. Airlines are forced to fly some loss-making regional routes to gain access to the best airport slots in Delhi and Mumbai.

But the industry’s underlying problem is overcapacity. State subsidies for Air India mean some routes are flooded with too many seats. The larger issue is a race for market share in what will become one of the world’s biggest markets for air travel. This problem looks poised to get worse before it gets better. Qatar Airways has plans to start a new full-service carrier in India with over 100 new jets. GoAir and Vistara, two fast-growing Indian carriers, plan to launch their first international flights in October. The lure is tomorrow’s profits. The upshot is losses today.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.