The recent gas transit deal between Russia and Ukraine, and their national gas companies Gazprom and Naftogaz respectively, has comforted Europe just about when the first cold spells started to bite. The 5-year contract is essentially a two-layered construct, with a 65 BCm per year throughput take-or-pay requirement for 2020 and a 40 BCm per year threshold for 2021-2024.

Five years is the median of both sides’ wishes, as Gazprom wanted a one-year bridge contract until it brings Nord Stream-2 and Turkstream onstream, whilst Ukraine wanted a 10-year contract that would keep the volumes Gazprom transits at least as high as previously.

The end result is acceptable to both, at the same time for all different reasons both sides see it as a non-perfect way to settle the transit issue.

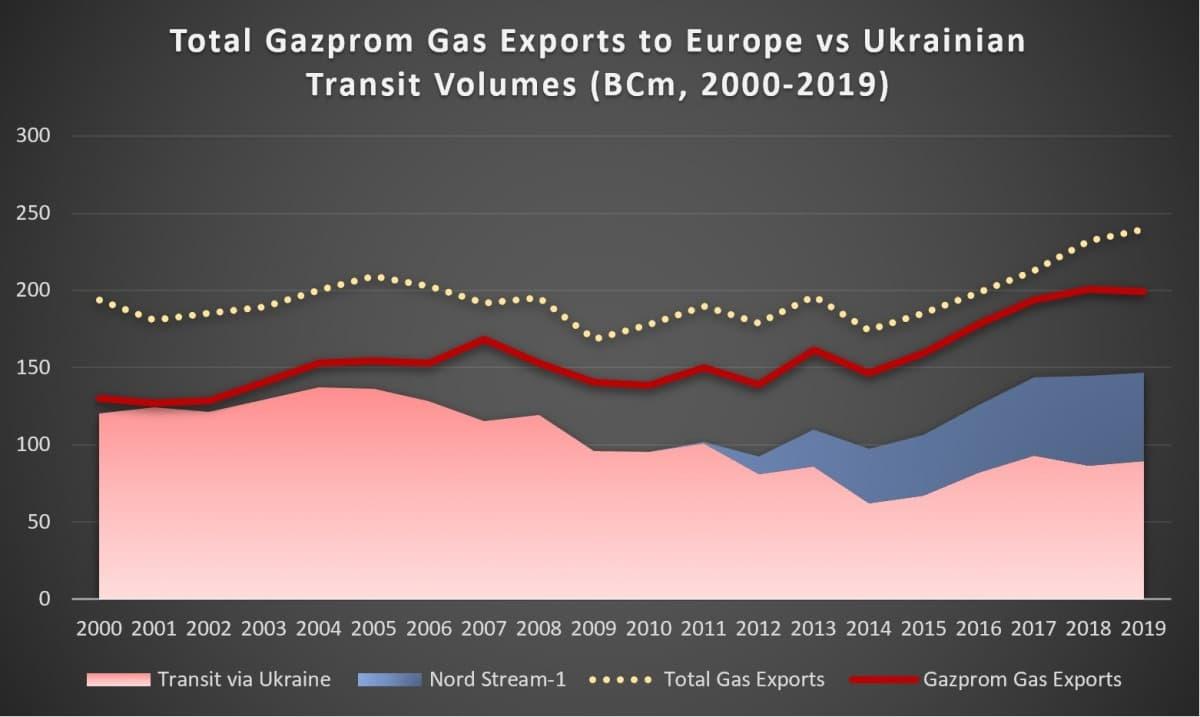

The gas deal, concluded a couple of days before Christmas after a negotiations tour encompassing Paris, Berlin and Minsk, builds on the relative normalization of the Ukrainian gas transit volumes. After they’ve dropped to 60-65 BCm per year in 2014 and 2015, the transited gas volumes have been hovering around 90 BCm per year ever since. This year was no exception to this, with 89.58 BCm of Gazprom-supplied natural gas finding its customers in Europe via Ukraine. Everybody knew that Nord Stream-2 would result in a sudden drop of transit volumes (and consequently transit revenues for Ukraine, still around 1-2% of their GDP) – postponing the pipeline’s commissioning date was ultimately chosen as the best scenario to prepare Ukraine for the change.

Graph 1. Russian Gas Exports in 2000-2019 (billion cubic meters per year).

Source: Gazprom, Author’s Data, Nord Stream.

By agreeing to a 25 BCm per year drop after 2020, the deal effectively confirms that Nord Stream-2 would be commissioned this year. Why not 55 BCm per year, one might ask – nominally that is the new gas conduit’s throughput capacity. However, it should be noted that it took Nord Stream-1 an unconscionably long time to hit nominal throughput capacity – 7 years, to be precise – primarily due to Brussels obstructing to Gazprom bidding for the other 50 percent of the OPAL pipeline abutting Nord Stream. This decision was entirely administrative in its nature since there were and remain no other bidders for OPAL capacity other than Gazprom. The same might be expected for Nord Stream-2, as well. Confronted with the ire of post-Soviet states that repine against Nord Stream’s exterritoriality (i.e. neither Poland, Ukraine nor anybody else would get transit revenues from it), the European Commission is highly unlikely to allow Nord Stream-2 to work as presumed.

The Gazprom Perspective

Flirting with the idea of ending Ukrainian gas transit once and for all, Gazprom wanted to commission both Nord Stream-2 and TurkStream before the Naftogaz contract ran out in December 2019. Thus, it could declare that it has the physical availability of other conduits, inevitably state-of-the-art and hence more efficient, hence subsidizing Ukraine’s economy by means of gas transits no longer serves the interests of the Russian pipeline export monopoly. This might have been achieved were it not for the unprecedented amount of obstructionism both projects witnessed – look no further than the Danish permission-granting saga or Bulgaria’s EU-buttressed foot-dragging on its participation in TurkStream.

Having received the Danish construction permit in late October 2019, Nord Stream 2 shareholders intensified pipe-laying works so as to build their bargaining power. All this was cut short by the Trump Administration sanctioning the seemingly weakest point in the whole chain – the Swiss pipeline-laying company Allseas. Apart from further antagonizing European business interests, this decision also resulted in Nord Stream 2’s commissioning date being moved to mid-2020 and Russia hitting a more conciliatory tone on the Ukrainian issue. Yet whatever the appearances, Gazprom perceives the current Ukrainian gas transit deal as a bridge to a better future, a worthwhile short-term concession so that its long-term plans are not jeopardized.

The biggest reputational loss vis-à-vis the Russian populace is indubitably the paying out of the $2.9 billion fine, however for Gazprom now the biggest headache is to finish the pipelaying works as Allseas seems to have backed out of it under direct US threats to withdraw immediately. Gazprom had the required sum safely laid aside and ready for transfer, whilst the necessity to do the pipelaying alone caught it completely by surprise. Gazprom has its own pipelaying vessel, having bought Akademik Cherskiy in 2015, yet itself moving it from its base in Nakhodka on the Far East to the Baltic Sea would take almost 2 months, not to speak of its generally slower pipelaying speed. Thus, Gazprom will finish Nord Stream 2 and reduce its Ukraine exposure, just not now.

The Naftogaz Perspective

The Ukrainian state-owned Naftogaz has been facing a plethora of dire prospects for quite some time – first and foremost the transit revenues were only scarcely put to the purpose of modernizing their gas transportation infrastructure. Domestic gas production could’ve potentially become the solution yet because of never-ending business conflicts that pitted local oligarchs against each other, as well as burdensome upstream terms and conditions, gas output stagnated for some years already and will most probably drop y-o-y in 2019. Against such a difficult background, the given outcome is definitely a success for Naftogaz – it secured the payment of a long-delayed $2.9 billion Stockholm arbitrage ruling from 2017, avoided the potentiality of a 1-year transit contract and got a relatively long-term deal.

Taking this year’s almost 90 BCm transited volume as a reference basis, even if we are to fully discount Nord Stream 2 (55 BCm per year) and the second line of TurkStream (15.75 BCm per year, the first is fully committed to Turkey), there still remains some 15-20 BCm per year that will be surely transited via Ukraine in a post-2025 landscape. Should Nord Stream 2 continue to be marred by arbitrary obstructions, even 40 BCm per year might stay as a take-or-pay threshold. Gazprom seems to have grown accustomed to the idea of keeping some sort of commitments vis-à-vis Ukraine, especially now when building another gas pipeline to Europe would be seen as pure folly, it remains to be seen whether Kiev can get used to significantly less transit revenues.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.