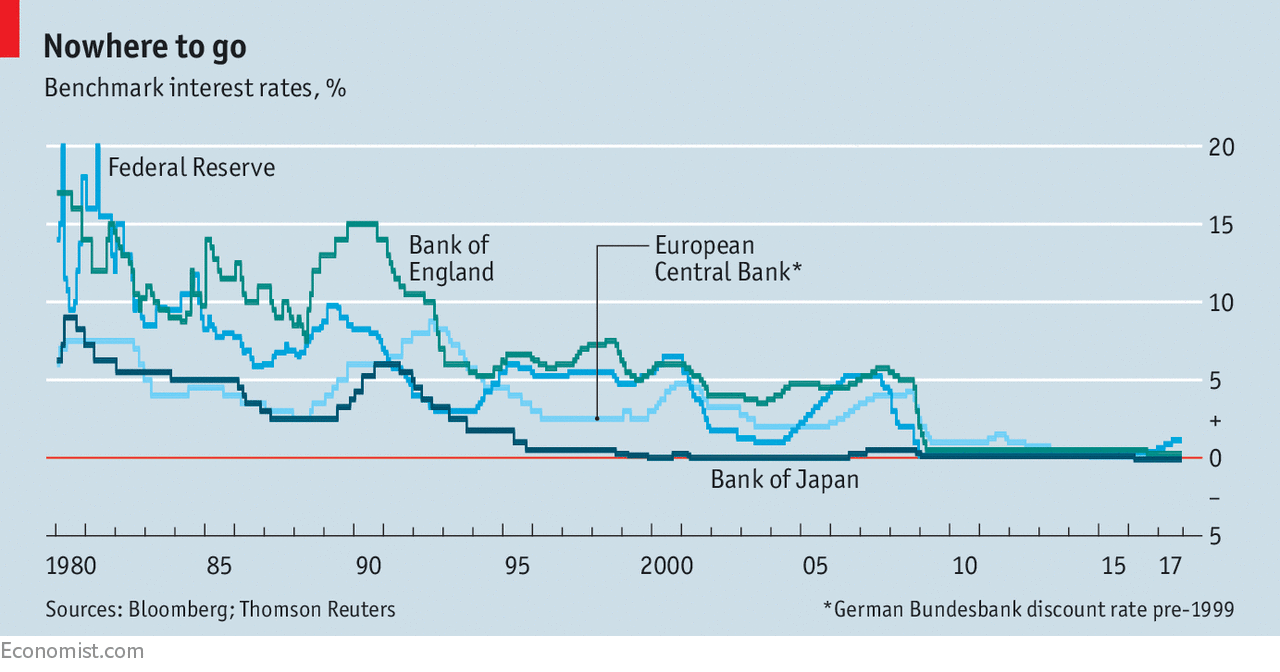

ONE day, perhaps quite soon, it will happen. Some gale of bad news will blow in: an oil-price spike, a market panic or a generalised formless dread. Governments will spot the danger too late. A new recession will begin. Once, the response would have been clear: central banks should swing into action, cutting interest rates to boost borrowing and investment. But during the financial crisis, and after four decades of falling interest rates and inflation, the inevitable occurred (see chart). The rates so deftly wielded by central banks hit zero, leaving policymakers grasping at untested alternatives. Ten years on, despite exhaustive debate, economists cannot agree on how to handle such a world.

During the next recession, the “zero lower bound” (ZLB) on interest rates will almost certainly bite again. When it does, central banks will reach for crisis-tested tools, such as quantitative easing (creating money to buy bonds) and promises to keep rates low for a long time. Such policies will prove less potent than in the past; bond purchases are less useful, for instance, when credit markets are not impaired by crisis and long-term interest rates are already low. In the absence of a solid policy consensus, the use of any unorthodox` tool is likely to be too tentative to spark a fast recovery.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.