MANY people complain that the finance industry has barely suffered any adverse consequences from the crisis that it created, which began around ten years ago. But a report from New Financial, a think-tank, shows that is not completely true.

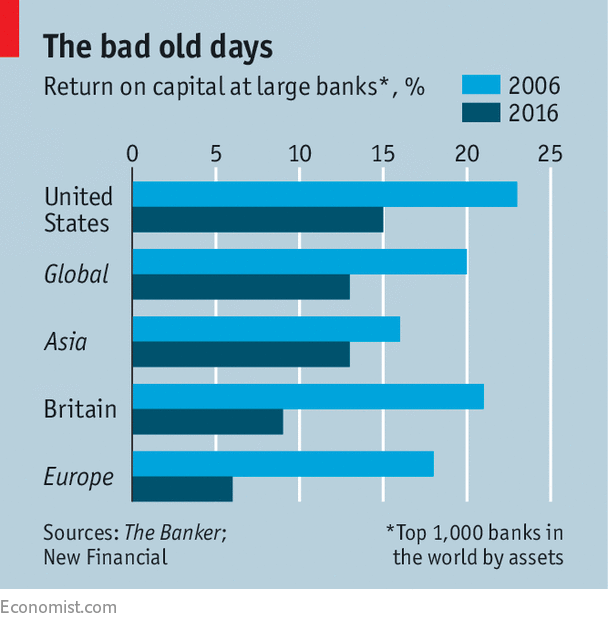

The additional capital that regulators demanded banks should take on to their balance-sheets has had an effect. Between 2006 and 2016, the return on capital of the world’s biggest banks has fallen by a third (by more in Britain and Europe). The balance of power has shifted away from the developed world and towards China, which had four of the largest five banks by assets in 2016; that compares with just one of the biggest 20 in 2006.

The swaggering beasts of the investment-banking industry have also been tamed. The industry’s revenues have dropped by 34% in real terms, with profits falling by 46%. Return on equity has declined by two-thirds. Staff are still lavishly remunerated, but pay is down by 52% in real terms. (Perhaps it is time for a charity single: “Buddy, can you spare a Daimler?”) The relative importance of different divisions has also shifted, with the revenues of the sales, trading and equity-raising departments shrinking more than the merger-advice or debt-raising divisions.

This last change reflects market developments. In 2016 stockmarkets were smaller, as a proportion of GDP, than they were in 2006, despite the record highs on Wall Street; that was because Europe and Asia have not performed as well. Both government- and corporate-bond markets were bigger than they were a decade earlier. Although the crisis started because of overindebtedness, corporate-bond issuance has doubled in real terms over the decade, while the volume of stockmarket flotations has fallen by half.

Meanwhile the game of “pass-the-parcel” of assets around the markets has speeded up; trading volumes in equities, foreign exchange and derivatives have increased in real terms. In the corporate-bond market, trading in American securities has grown but trading in European debt has declined.

In the midst of the crisis, central banks stepped in with quantitative-easing programmes to buy financial assets. This has had profound effects, most notably in the bond markets, where yields have fallen to historic lows (and hence prices have risen). In contrast to equities, the value of both corporate and government bonds is significantly higher, relative to GDP, than it was ten years ago.

This has proved to be a pretty decent climate for money managers, who earn fees based on a percentage of the assets they invest. The industry’s pre-tax profits rose by 30% between 2006 and 2016, despite the growing market share of low-cost index-tracking funds at the expense of actively managed ones. At the other end of the cost spectrum, hedge funds, private equity and venture capital have all increased their assets, relative to GDP. The asset-management industry has become more concentrated. The 20 largest firms control 42% of assets, up from 33% a decade ago.

Overall, the authors of the report remark that “it is perhaps surprising how little has changed”. It may be less surprising if you consider that finance has two faces: first, as a driver of the economic cycle via credit expansion; and second, as an instigator of crises when creditors lose confidence. If markets are plunging and banks failing, as they were in 2008, it is understandable that the authorities do all they can to stabilise markets and rescue banks. As Tim Geithner, a former treasury secretary in America, put it: “The truly moral thing to do during a raging financial inferno is to put it out.”

By making the banks take on additional capital, the authorities have at least made the system less likely to suffer an exact repeat of the last crisis. But the world is still marked by a combination of high asset prices and high levels of debt. Outside the financial sector, there is even more debt than there was ten years ago; the combined total of government, household and non-financial debt levels are 434% of GDP in America, 428% in the euro zone and 485% in Britain.

In other words, the borrowing has been shifted to other parts of the economy; but that makes the finance industry no less vulnerable. A sudden fall in asset prices, or a sharp rise in interest rates, would reveal the jagged rocks beneath the surface. Central banks know this; that is why they are so cautious about unwinding monetary stimuli. At the heart of the next economic crisis will be the finance business; that is something that has not changed in the past decade.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.