Progress in developing treatments makes oncology research a favourite with investors

CANCER is a grim sort of growth market. By 2030 there will be over 22m new cases a year, up from 14m in 2012, according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer. But as the world marks World Cancer Day, on February 4th, scientists are speaking of a revolution in the battle to beat it. Money managers’ ears have pricked up. Oncology investing is “hot”.

The most straightforward way to invest in treating cancer is through shares in companies that sell blockbuster drugs. Alternatively, biotech indices track a basket of companies, of which typically 40% are oncology-related. Big Pharma now buys rather than builds much of its innovation. So backing oncology startups can be an especially lucrative (if risky) approach. According to CB Insights, a research firm, equity investment in cancer-therapeutics startups has grown from $2bn in 2013 to $4.5bn in 2017. Take Juno Therapeutics, founded in Seattle in 2013 to develop immunotherapy drugs. It was acquired on January 22nd by Celgene, a Biotech giant, for a whopping $9bn.

Eric Schmidt of Cowen, an investment firm, believes that oncology offers “the highest returns on investment of any therapeutic category”. Three developments explain the frenzy. First, demand for cancer treatments is rising as prevalence increases and the world’s middle classes—who can afford insurance—expand. Between 2012 and 2016 the global costs of cancer-related treatments grew from $91bn to $113bn, according to IQVIA, a health-data firm. They are expected to rise to $147bn by 2021.

Second, scientific progress, particularly around manipulating genes and cells, has been astonishing. The pipeline of oncology drugs in clinical development has expanded by 45% over the past decade. Immuno-oncology (IO), whereby the patient’s own immune system is used to attack cancerous cells, is particularly in vogue. Goldman Sachs, a bank, values the IO market at around $140bn and, despite calling the field “overhyped”, predicts it could grow by another $100bn.

Third, cancer enjoys faster regulatory approvals than other diseases. As Christiana Bardon, of Burrage Capital, puts it, “patients are dying and they are dying now”, so regulatory hurdles are lower.

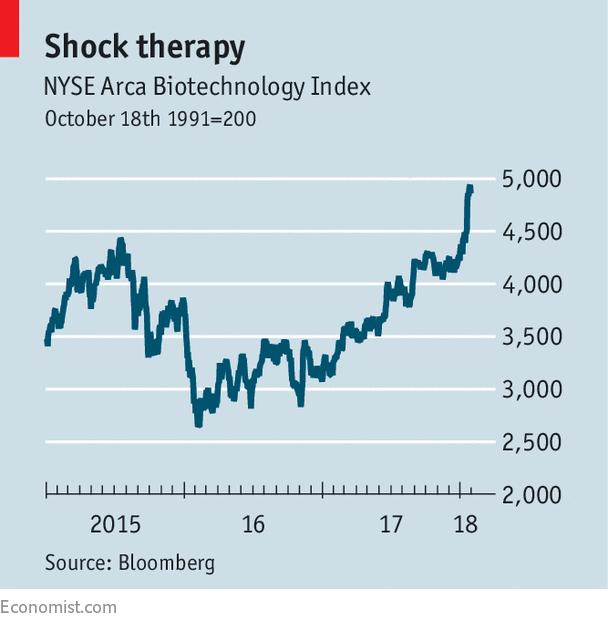

But as with any hot commodity, the line between well-founded excitement and unfounded giddiness is thin. Andy Smith, from Edison Investment Research, points out that it is still early days for treatments like CAR-T (a specific type of IO). He worries about an “implied halo”, comparable to the one that now benefits cryptocurrencies. Investments in oncology and in biotech more generally can also resemble cryptocurrencies in their wild price swings (see chart). Another risk is that new treatments, however brilliant, may never be cheap enough to sell. CAR-T could well be game-changing but only a handful of treatments (which cost around $500,000 per patient) have reportedly been sold.

Iain Foulkes, director of research at Cancer Research UK (CRUK), a charity, worries that much of the welcome inflow of capital into cancer research is chasing similar opportunities. Rarer types of cancer may get neglected. Partnerships between investors and research institutes can help overcome this. A recently announced tie-up between Merck, a pharmaceutical giant, and CRUK is an example. The drug company will have the right to develop products from any discoveries made; CRUK will share in profits and royalties.

A surge in “ethical” investment, blending financial returns with doing good, will also help. One initiative is a $550m Healthcare Innovations Fund, from Deerfield, an investment firm, a good chunk of the profits from which goes to underserved research areas. Another is a $470m Oncology Impact Fund, raised in 2016 by UBS, a bank, for early-stage oncology research. A sizeable share of the profits go to neglected research areas and to improving access to cancer treatment in poor countries. Already, early successes have allowed the fund to “give back” $2.5m. Its greatest potential lies in future royalties from drugs that make it to market.

Mark Haefele of UBS thinks drug companies should consider similar structures. He notes a desire among clients for more than just financial returns. But he adds that it starts with a compelling investment opportunity—and “few fields are as compelling right now as early-stage oncology.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.