Executive Summary

The Resurrection of Ford Motor Company

In late 2006, Ford Motor Company was struggling. Losses for that year came in at a staggering $12.7 billion, down dramatically from $1.9 billion in profits the prior year. Four years later, profits had rebounded to $6.6 billion, subsequently rising to $10.8 billion in 2016. Incredibly, Ford’s turnaround took place amidst the US’ Great Recession, which hit its auto industry particularly hard. Most impressively, while Ford was in the throes of arranging its major reversal, its closest rivals, Chrysler and GM, were negotiating bailouts with the US federal government’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP).

Ford’s resurrection, led by President and CEO Alan Mulally, is one of the great contemporary examples of organizational design and optimization at work. Through a structured and well-sequenced overhaul, Mulally consolidated Ford’s regional operations into a single global one, eliminated duplication and resource waste, shrunk excess and non-value-adding platforms, and improved goal clarity across the firm. The result: a new, single, faster, stronger, streamlined company and strategy, which Mulally dubbed “One Ford.”

This article is, at its core, about organizational design and optimization. It begins with an introduction to the discipline’s foundational principles, followed thereafter by an exploration of the many concepts and themes that Alan Mulally so adeptly used in his turnaround of Ford’s fortunes. Finally, I conclude with a practical how-to guide for restructuring sub-optimized organizations, leaning on my 20+ years of experience as a global restructuring specialist.

What Is Organizational Optimization?

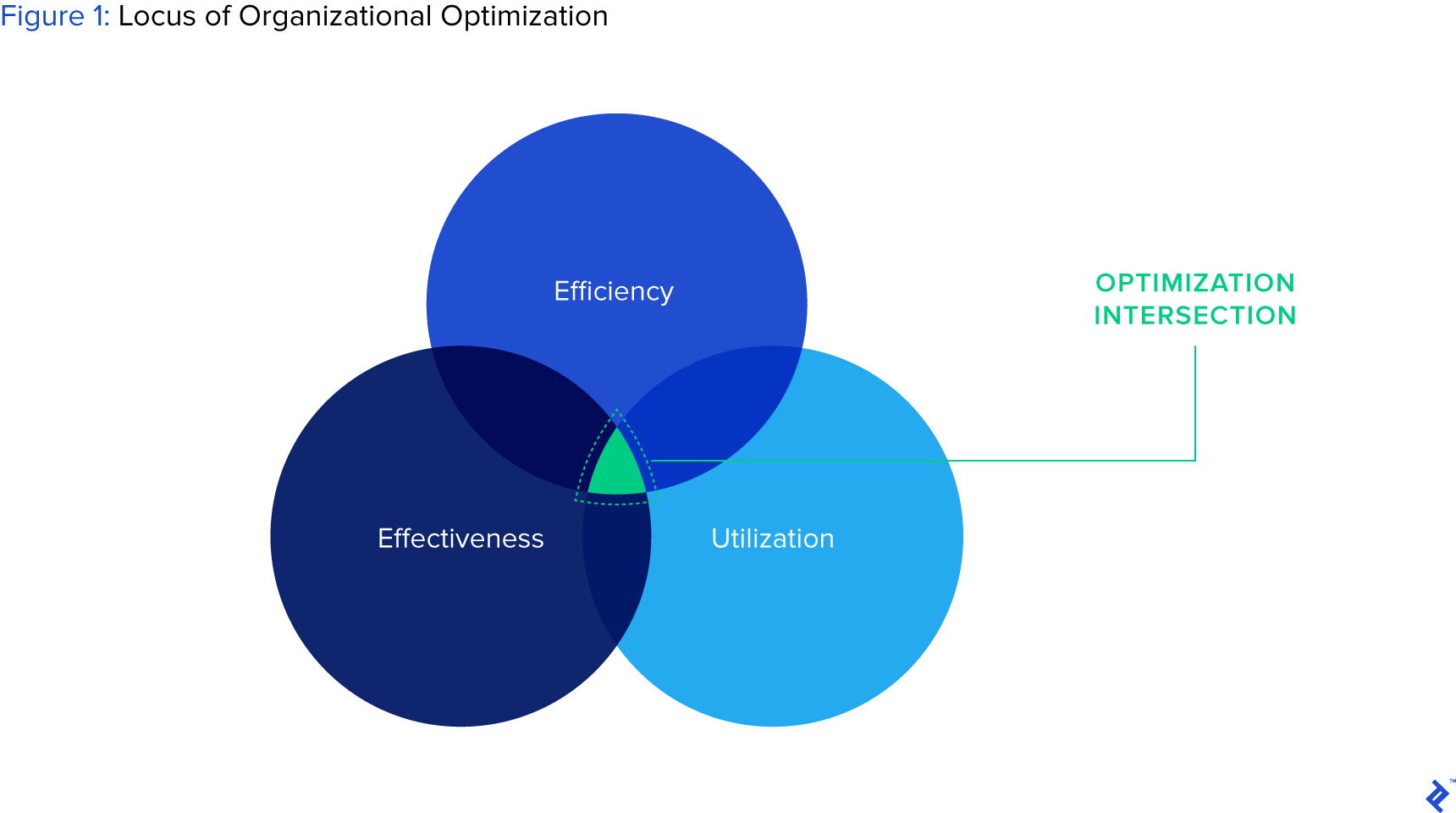

Organizational optimization can be defined as the alignment and leveraging of an organization’s resources to realize its stated goals/objectives. Organizational optimization exists at the intersection of high efficiency, high effectiveness, and high utilization of all relevant and then currently available resources at an organization’s disposal.

Why Should Companies Bother with Organizational Optimization?

Staying Ahead in a Rapidly Changing World. First, businesses today operate in dynamic environments; environments punctuated by periods of extreme volatility, rapidly changing technology, and globalization. These factors are made even harder to manage by a discerning yet fickle global consumer class whose tastes or preferences seem to change by the moment. Where effectively exploited though, organizational optimization has proven itself a reliable driver of short-term and long-term goals, which companies may leverage to stay ahead of their respective market forces.

The Arrival of the Future of Work. Second, historic organizational structures are evolving. Specifically, ongoing workplace changes are presenting new challenges to managers who must now also contend with, manage, and motivate geographically distributed workforces. These new structures include a higher incidence of remote work (both individual and group), greater use of part-time work by corporations, and an increasing reliance on temporary and contract employee models. Managing such dispersed groups at optimal cost and performance effectiveness is and will continue to be challenging and will require a structured and deliberate rethink of organizational design.

Achieving Strategic Advantage. Approaching the corporate challenge from a different perspective, non-optimized organizations playing in arenas comprised of relatively optimized competitors risk becoming less competitive and thus more vulnerable. By optimizing one’s organization, hiring and deploying the right skill sets, and aligning goals across one’s company, one’s business will be better positioned to respond to unexpected changes in the marketplace and will be better able to drive toward one’s corporate priorities quicker and more effectively.

Acquisitive Growth Strategies Have Long Been the Norm. M&A, as the corollary to organic growth, is, at this point, a mainstay of the global corporate fabric. And getting the post-merger organization structure right—aligning cultures, human resources, priorities, and workflows—is often the key to unlocking the projected synergies and value-potential of the business combination.

To add figures to theory, according to a Harvard Business Review article that in turn leans heavily on research by McKinsey & Co., only 16% of mergers deliver on soft and hard goals on schedule. Further, 41% take longer than expected, and in 10% of cases, the new organization is value dilutive rather than accretive. Here too, deliberate strategies around organizational optimization offer a proven and reliable roadmap for greater success.

Case-Study: InBev’s Acquisition of Anheuser-Busch

In 2008, Belgium-based InBev completed the $52 billion acquisition of US giant Anheuser-Busch. At the time of the acquisition, Anheuser-Busch dominated the US market with 48% share while InBev, despite being one of the world’s largest brewers, had a modest share in the US and no domestic production capacity.

The business combination was projected to achieve $1.5 billion in cost synergies over the first three years; however, by 2011, the newly formed Anheuser-Busch InBev reported synergies of $2.3 billion, which was just shy of 50% greater than its initial projection. Over the same period, margins expanded 600 basis points from 33% to 39%.

The keys to Anheuser-Busch InBev’s success were three factors:

- The first was a relentless focus on efficiency gains through the elimination of any and all redundancy. This began with the consolidation and streamlining of both companies’ procurement, engineering, logistics, and R&D divisions into one, but was quickly followed up by deliberate knowledge transfer across the organization around best practices and efficient processes. The result was $1 billion in cost savings within a year and an increase in throughput.

- The second was the implementation of CEO Carlos Brito’s “one firm, one culture” policy, which tolerated zero complacency, drove tight cost controls via its zero-based budgeting practice, enforced personal accountability, and instilled the highest levels of personal and corporate integrity. This culture also endowed its globally dispersed leaders with the ability to make decisions quickly and in isolation at a local level—a strategy that allowed the company to stay close to its regional and local customers even at scale and thus react quickly to their wants, needs, and preferences.

- The third was implementation intensity. Carlos Birto and InBev’s well-worn practice of no compromise in integrations drove elimination of underperforming brands (including Peroni and Grolsch beers), large layoffs (came in at 6,000 in total), and supplier consolidation, all in record time. Integration would and could never be complete until every last “i” and “t” that had been scripted as part of the pre-merger integration plan had been dotted and crossed.

Through the optimization process, AB InBev realized dramatic cost reductions over the period. Between 2008 (year of the acquisition) and 2011, it saw:

- Sales and marketing expenses reduced from 15.9% to 13.2%, as a percent of revenues;

- Distribution expenses declined from 11.5% to 8.5% of sales, as a percent of revenues;

- Administrative costs dropped from 6.2% to 5.2%, as a percent of revenues.

The Integration Trap

The fallacy of the integration trap is one that wrongly presumes that mergers and acquisitions are a sure way to create value quickly or to achieving growth with lower risk. To avoid this trap, early, structured, and diligent work to optimize the combined organization must be undertaken. This is done by first mapping both companies in detail to the ends of identifying areas of overlap, waste, and capability gaps before going on to eliminate said areas of overlap and waste as well as design effective solutions for the capability gaps.

Next, the acquiring managers must then map and fully understand all the critical processes and workflows across both organizations before diligently working to standardize and integrate them. Finally, the surviving personnel, ex-post, must develop common and unifying goals, solicit buy-in at all levels, and execute relentlessly to achieve them.

The Optimized Organization

According to restructuring theorists and practitioners, optimizing organizations requires focus in four primary areas that I’ve dubbed elements: (1) process redesign; (2) structured workforce development; (3) improved role clarity; and (4) transparent goal setting. Each element can and is often executed in isolation; however, the four work exponentially better as an interdependent collective, creating a fully congruent system able to drive optimal performance. A more fulsome understanding of each is as follows:

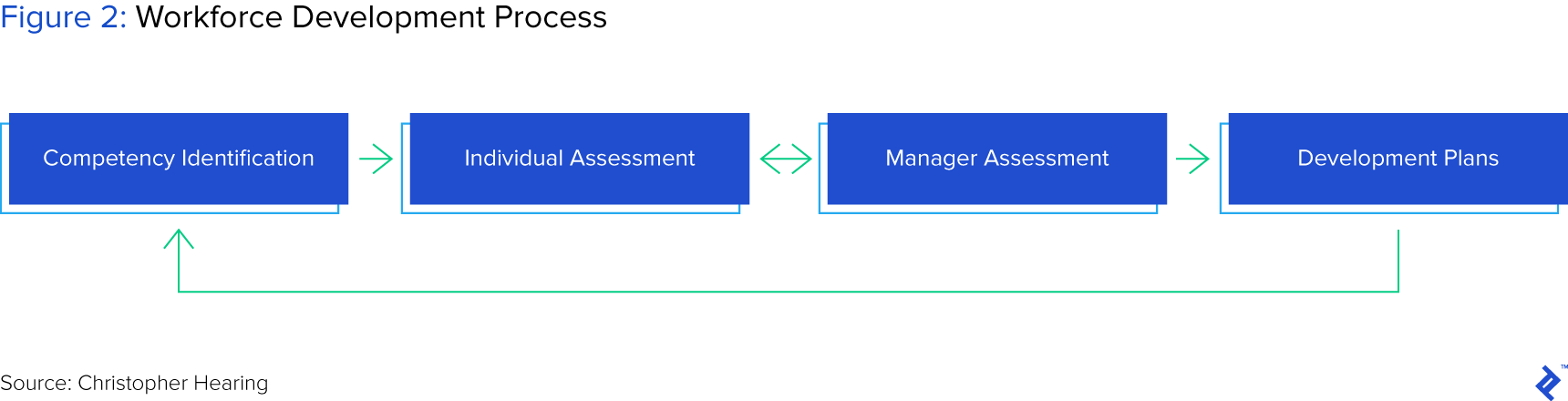

Process Redesign. This first element of organizational optimization involves redefining and re-streamlining existing workflows to yield a more effective and efficient organization. This is most effectively accomplished by asking the following question, for every foundational process and task utilized by the company: “How does this given or redesigned process benefit our customer?” By asking and answering the question repeatedly and working single-mindedly to eliminate tasks where the answer is either opaque or negative, one very quickly eliminates non-mission-critical tasks that suck up valuable time and resources.

More to the point, this process should be applied methodically to the following key operating areas within an organization: (1) costs; (2) product/service quality; (3) process efficiency; and (4) speed of deliverance or execution.

Workforce Development. The workforce development element is the most difficult of the four focus areas, though the most fundamental to overall organization optimization. Workforce development seeks to match the right skills to the right strategic priority and seeks to do so at the right cost. Employees without the right skills or whose skills are out of alignment with the corporate priorities will either need to be retrained or will have to personally evolve as value-adding members of the restructured organization…or risk separation.

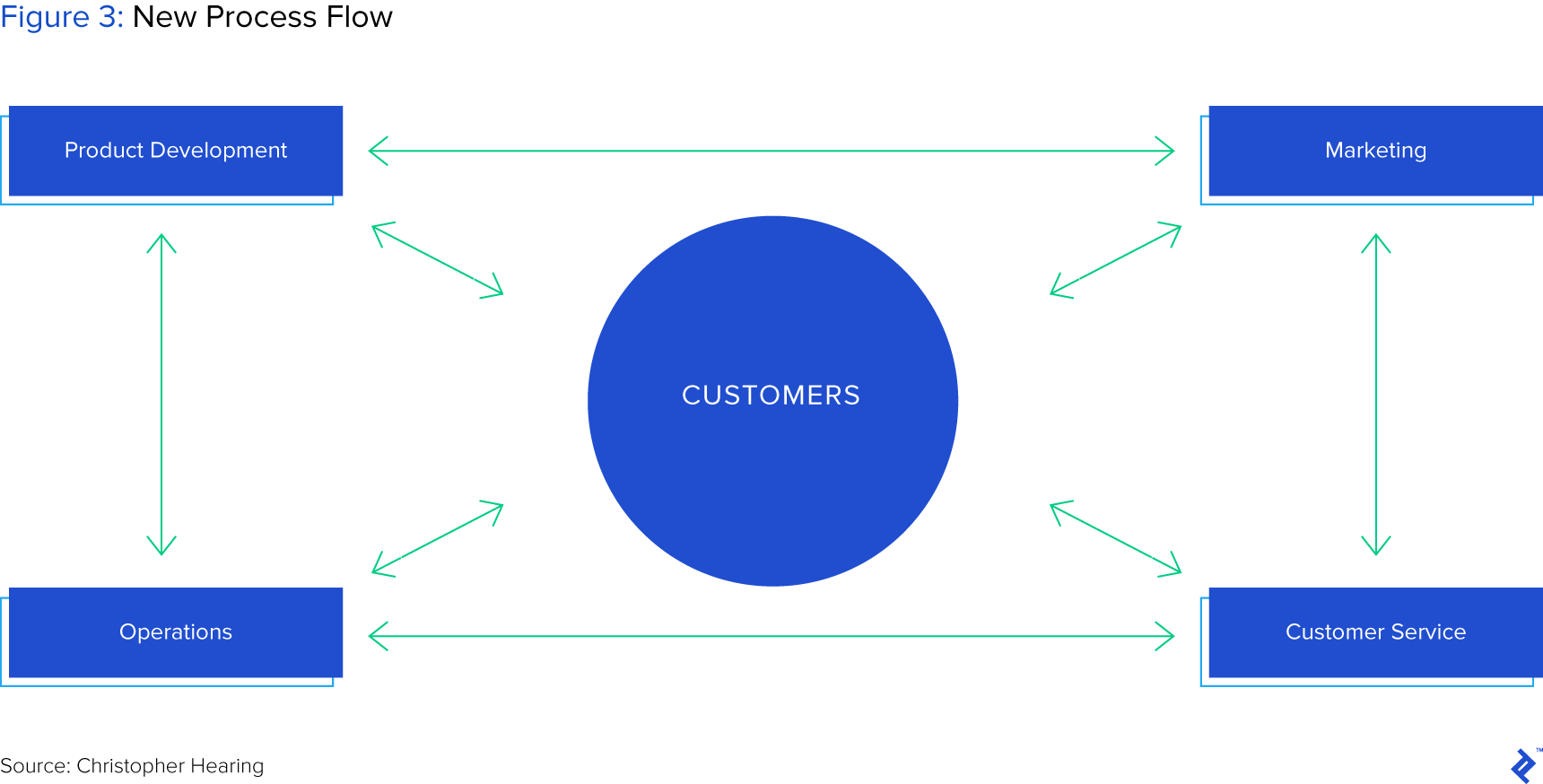

In my experience, a reliable set of steps to go about workforce development is as follows: First, begin with a competency assessment—i.e., a tool for identifying unique and/or appropriate skills and behaviors required to drive an organization, unit, or team toward its goals. These skills and behaviors should then be assessed against the backdrop of both the availability of complementary and substitutable capabilities across the organization as well as the employer’s needs.

It is at this point that a plan to improve employee capabilities may then be developed and implemented for best-in-class results, optimized retention, and greatest cost-effectiveness. Once developed and broadly implemented, the competency assessment process should become an ongoing tool used routinely to develop and drive success-behaviors and desired outcomes across the organization.

Role Clarity: Role clarity, as its title suggests, is optimized when, first, each employee is clear about the company’s priorities; second, in his/her unit’s role in achieving it; and third, about his/her tasks and execution responsibilities thereto. This includes a clear understanding of expectations, outputs, timelines, success metrics, and behaviors. Through role clarity, organizations typically experience material improvements in individual and collective effectiveness, and as a secondary benefit, are better able to measure and incentivize performance.

Role clarity can be derived by executing according to the following:

- Defining and communicating role descriptions, responsibilities, and skill-assessment parameters;

- Establishing the rules of accountability through clear documentation and communication of what constitutes success;

- Setting clear goals for individuals or groups/units, in line with the grander corporate objectives and with specific timelines in place; and

- Continuous practice, communication, and reinforcement of these three habits.

Goal Setting: The last key focus area is setting simple, clear, and attainable goals, and aligning individuals and units accordingly. In accomplishing this, I have found that designing visual roadmaps that illustrate how each employee’s roles, regardless of level and title, will support the attainment of the organization’s objectives, has no equal. Better still and similar to role clarity, these roadmaps also double as useful motivational tools where applied appropriately.

The above notwithstanding, goal alignment can be achieved through what the industry refers to as a goal cascade. Goal cascades are accomplished by setting the highest level corporate goals first and then working down the organization structure so that divisions, departments, teams and, lastly, individuals and their goals, are set single-mindedly in support.

Goal cascades have multiple organizational benefits, including:

- Ensuring that all employees are driving in the same direction, and their efforts are focused on the activities that the corporate leaders have designated most important;

- Fostering cross-team alignment and teamwork given each employee across groups at each level is broadly driving toward the same priorities.

Without question, top-down goal cascades create the necessary corporate infrastructure to ensure that strategic priorities are met. However, it is important that organizations work hard not to become too rigid and instead allow for some latitude where certain employees seek to pursue goals not directly or immediately accretive to the management level above.

The Role of Organization Structure in the Optimization Model

Simply stated, organization structure determines the accountability and authority within an enterprise. Where structures are not designed in support an implementation strategy for optimization, probabilities of success decrease materially. This is even truer where day-to-day operations are concerned and most critical when an organization is attempting to shift from one culture and set of behaviors, incentives, and measurement patterns to another.

Repercussions of Underestimating the Informal Organization

“A bad system will beat a good person every time.”– W. Edward Deming

Though formal structure is important, it is my experience that leaders must never ignore the informal organization that dwells within. The informal organization is the interlocking social structure that governs how people work and socialize with each other in practice and is at least as powerful as the formal. The proverbial water-cooler has long since been emblematic of the quintessential 20th century American corporation’s informal organization, and it’s one that won’t soon be forgotten.

The ability to deconstruct, understand, and leverage the informal organization within a company can be an important factor for successfully diffusing change. Specifically, these structures can exist as effective back-channels that leaders may leverage to drive changes in an organization’s behavior or solicit buy-in for new initiates. It is worth noting that as major changes are implemented, leaders must be careful not to disrupt or make an enemy of an informal organization’s workings. Systems always self-protect and self-reinforce and, more often than not, violently expel alien agents that they deem a threat to their internal constitution or survival.

Ultimately, leaders of a corporation may ask the following questions to assess the effectiveness of their organization and also use these questions to determine whether a reorganization is appropriate:

- Are we organized to best serve our customers?

- Are we organized to achieve our strategic objectives?

- Are our internal resources focused on value-added activities that leverage our core competencies?

Building a Sustainable Optimization Program

The first rule to building an optimization program is that one should never consider it a one-time, short-term fix to what are likely deeply structural problems. While meaningful benefits can be realized from a single optimization effort, the true gains compound over the long term when the right habits become a part of the organization’s DNA. Thus, developing a culture that embraces, enforces, and self-propagates ongoing optimization is fundamental to ongoing success.

In my experience, building a culture of optimization and efficiency can be achieved by adhering to the following steps. First, solicit buy-in across your organization—i.e., from your most junior resource to your most senior executive, but most especially amongst your corporate influencers. Secondly, establish and clearly communicate the new behavioral requirements needed for the organization to successfully transition cultures. Third, aggressively incentivize these behaviors across the organization. Fourth, and this is for the most ambitious and adept amongst you, establish short to medium term challenges to gamify engagement at all levels. And finally, continue to enforce the practice of this new culture and habits until said habits become a part of the organization.

The following are the key attributes critical to an optimized success culture:

- Open and Transparent Knowledge Sharing: Openness builds trust and increases collaboration and understanding across employees.

- Collaboration and Teamwork: Closely related to knowledge sharing, collaboration optimizes effectiveness and thus outcomes across an unchanged base of resources.

- Top-to-Bottom Cost and Resource Mindfulness: Constantly seeking cost improvements improves the company’s margin profile, in turn creating more financial resources for further reinvestment into additional human resources, culture shifts, and infrastructure to drive outcomes.

- Openness and Proclivity to Change: Usually the most difficult to achieve, a culture that embraces change at both the individual and collective levels is indispensable to a grander culture of optimization.

The Leadership Challenge

Building an optimized organization is a leadership challenge that extends beyond human resources. Implementing an organizational optimization program is disruptive and often risky, given that it inherently forces employees to act in new, often uncomfortable ways—ways that include focusing on open knowledge sharing, transparent accountability, and widespread collaboration, all of which require personal vulnerability and, thus, discomfort.

Where successful, however, organizational design and optimization have the potential for transformative short- and long-term rewards, including driving out inefficiency and ineffectiveness, improved margins, and improved customer experiences. Once the new culture takes root, as has been the case at Alan Mulally’s Ford and Carlos Brito’s Anheuser-Busch InBev, the system often becomes self-sustaining, self-policing, and self-propagating, paying dividends for years to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.