Will it be able to fill the gaps left by smaller producers?

Oil Traders are inherently strong-stomached, but even for them October has been a woozy month. On October 3rd the price of Brent crude reached $86 a barrel, a four-year high. On October 23rd it slid to $76, on the news that demand might ebb, stockpiles rise and production increase. At the centre of this is Saudi Arabia, the world’s most powerful petrostate. Khalid al-Falih, the country’s oil minister, said on October 23rd that the kingdom was prepared “to meet any demand that materialises”. But that is not an easy task.

Exports from Iran have plunged and are due to fall further after November 4th, when new American sanctions take effect. Even as America’s crude production soars, President Donald Trump has demanded that the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (opec) boost output to lower prices. Saudi Arabia seems keen to appease him, both because it supports the sanctions and because of anger over the killing of Jamal Khashoggi, a journalist, in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. But the gains from producing more are uncertain. Both opec and the International Energy Agency (iea) have cut their forecasts for oil demand in 2019.

Even if Saudi Arabia wants to fill the gap left by Iran, it is not clear that it can. That is in part because Saudi output is already so high. As Iranian exports have dropped since May, when Mr Trump announced the sanctions, Saudi Arabian exports have picked up. The kingdom is producing more than 10.5m barrels of oil a day (b/d); officials claim the capacity to produce around 12m. “They can reach about 11m barrels with relative ease,” explains Neil Atkinson, head of oil markets at the iea. Analysts debate how quickly—or whether—the country can ramp up to 12m b/d. “They have never actually proven they can do that,” says Ehsan Khoman of mufg, a bank.

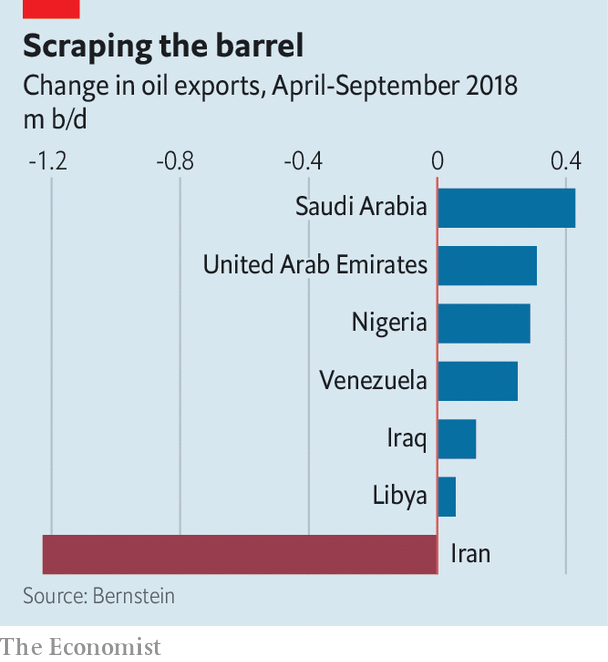

Saudi Arabia may also be unable to counter weakness in smaller petrostates, where supply could drop unexpectedly. In the past six months Nigeria, Libya and Venezuela have helped to offset falling exports from Iran. But they are a volatile trio.

The result may be further dramatic swings in the market, with Saudi Arabia’s oil production put to the test. “It is the first time in modern history that countries have faced so many restrictions at the same time,” according to Mr Atkinson of the iea. Much depends on just how far exports from Iran sink—some countries are pushing for waivers from sanctions. Mr Falih remains confident that Saudi Arabia can help provide stability. But as it increases output, spare capacity may reach a record low by the end of the year. “The more they produce, the less there is in the tank for any additional supply outages,” says Mr Khoman. Get ready for a bumpy ride.

Violence and political unrest make production in Nigeria and Libya prone to big swings. The situation is more extreme in Venezuela where, thanks to political turmoil, production is about half of what it was in early 2016. Still, Venezuela produced 1.2m b/d in September. Exports actually increased by 250,000 b/d between April and September, according to Bernstein, a research firm, equivalent to more than half the rise in Saudi exports in that period. There is ample room for Venezuela’s output to drop further.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.