On July 26, 2012, the European Central Bank president drew a line in the sand and framed his legacy.

It’s July 26, 2012. In financial markets, a dark storm is brewing, but on this Thursday morning it’s as if London doesn’t care: The sun bathes the waking city in golden light. Lancaster House, a Georgian mansion that sits between Buckingham and St. James’s palaces, is bustling with activity ahead of an investment conference convened by Prime Minister David Cameron. At a morning panel, several luminaries, including European Central Bank President Mario Draghi and Bank of England Governor Mervyn King, have been brought together to discuss challenges to the global economy.

As weighty as the subject is, and even though the euro is under siege as a three-year-old sovereign debt crisis wracks Europe, the room lacks a heightened sense of anticipation. “No one had planned this to be an event of great significance,” King recalls. “This is important in understanding what happened next.”

Chatting with his fellow panelists, Draghi seems almost preternaturally relaxed. He tells them, “Why don’t you take as much time as you want? I don’t want to say much.” And at first that seems to be the case. When he reaches the lectern, he starts off by telling the audience that the euro is like a bumblebee. It manages to fly contrary to the laws of physics. Now it must “graduate to a real bee.” Perhaps the analogy is familiar to Italians, or to entomologists, but mild bewilderment is spreading through the room.

Draghi carries on, rarely referring to his notes. Some six and a half minutes into his remarks, he looks down. Takes a breath. Folds his hands. “But there is another message I want to tell you,” he says in Italian-accented English. “Within our mandate, within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro.” He pauses and adds, leaving no doubt about his meaning, “Believe me, it will be enough.”

Whatever it takes. The rest of his speech after this 16-second episode is a blur to many people. But those three words stick.

What follows is the inside story of that moment and how it set the tone for Draghi’s term at the ECB. This reconstruction is based on interviews with dozens of central bankers, politicians, and officials across the European Union and the U.S. Some spoke on the record. Others requested anonymity. As he enters his final year at the helm of the ECB, Draghi said he wouldn’t comment for this article.

The story of Draghi’s pledge to save the euro really begins a month before he’ll make it. The euro area is an investors’ free-for-all, and the stakes are as high as they get: the survival of the single currency, which for Draghi, like many Europeans, is the emblem of a generation’s efforts to bring peace and prosperity to a continent torn apart by two bloody wars. Now, in the early summer of 2012, with financial markets doubtful that the weakest euro zone countries can repay their debts and with an economy plunging back into recession, the flaws of a single currency are all too apparent: 17 independent countries, a tangle of budgets, no unified governance, wildly different economies.

In this atmosphere, the leaders who make up the European Council gather in Brussels for a crisis summit—their 19th. They emerge in the early morning hours of June 29 with a clutch of commitments about joint bank supervision, budget coordination, and more centralized economic policymaking. It amounts to little more than a plan to come up with a plan, and, while some of the summiteers are desperate to enlist the ECB to forestall disaster, Draghi seems less than impressed. “I’m actually quite pleased with the outcome” is all he can bring himself to say. His message to the council is straightforward: You need to act; no ECB intervention will be effective without more integration—fiscal, economic, political.

For Draghi, the summit outcome at least confirms something he’s maintained since he took office eight months earlier. Despite the skepticism of investors and widespread popular resignation across the continent to a seemingly never-ending crisis, EU member states remain as committed to their union, and to the euro, as they were in the beginning. And yet markets seem to take little notice of the council’s vaguely worded commitments. Speculation against the euro continues. Draghi knows something more is needed.

Over the next several weeks he shuttles in and out of Frankfurt, where the ECB’s headquarters is, and across Europe, pondering his options. He’s asking people questions whenever he has a chance to. What could the ECB do? Why should it do something? How can it ensure that what it does will be successful? Those close to Draghi sense that something is in the air, but they can’t put their finger on what it is.

Investors are yearning for a bold signal, and Draghi—whose time at Goldman Sachs in the 2000s gave him an insight into the psychology of markets—knows the stakes. Klaas Knot, governor of the Dutch central bank, remembers asking him in early July: “Do you have something in mind?” Draghi’s answer: “Nothing concrete yet. But it needs to be big.”

And it will be. Whatever it takes. This isn’t a last-minute choice of words by Draghi in London, says Stanley Fischer, a former vice chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve who’s been a mentor of Draghi’s ever since he taught him as a Ph.D. student at MIT in the 1970s. “You can be sure he thought about that thing a long time,” he says. “But I don’t think I ever guessed that he would just come out one day and say it so clearly and simply. It was a masterstroke.”

Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, is sitting in the front row at Lancaster House only feet from where Draghi is speaking. It occurs to her that, with his pronouncement, he may have just saved the euro. Draghi himself doesn’t seem convinced at first. As the ECB president leaves the stage, Jim O’Neill, who at the time was the chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management, applauds Draghi’s “incredibly important comment.” Draghi’s response is little more than a verbal shrug.

One of the first people Draghi phones after the speech is Jens Weidmann. As president of Germany’s Bundesbank, Weidmann is one of the most influential policymakers on the ECB Governing Council. He’s also one of the most skeptical when it comes to unconventional policy steps. Convincing him would go a long way toward convincing Germans that their money is doing more than just bankrolling irresponsible governments on the shores of the

Mediterranean. Weidmann’s reaction is lukewarm. His opposition will harden only later, when it becomes clear that Draghi is considering buying sovereign debt.

For markets, the approbation that matters most doesn’t come until the following day. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande have what’s described in the media as a crisis telephone call and afterwards issue a joint statement. In it, they echo Draghi’s promise. “France and Germany are fundamentally tied to the integrity of the euro area,” the statement says. “They are determined to do everything to protect it.”

From that point onward, Draghi’s three-word utterance will frame ECB policy and shape his image as the poster boy of a new breed of activist central bankers. At the time, Draghi, as the guardian of the single currency, probably had little alternative to throwing the full weight of the ECB’s unlimited money supply behind the euro’s survival.

“Draghi understands that the euro is a deeply political project, and he’s made a big contribution to saving it,” says Wolf Klinz, a German Liberal Democrat member of the European Parliament. “His pledge to do whatever it takes was right, even though he may have subsequently taken loose monetary policy a bit farther than strictly necessary.”

The euro still exists, and its foundations have grown stronger: Governments have created a joint bank supervisor under the umbrella of the ECB, set up a permanent rescue fund to help struggling banks and countries, and are in the process of creating a road map for deepening the economic and monetary union.

Even with new measures, there’s no guarantee the euro will survive. Fueled by concerns over immigration, populism has surged and intensified skepticism about greater integration. Some among Germany’s political elites say Draghi is at least partly to blame. The idea of breaking free of the single currency has been debated in election campaigns across Europe and across the political spectrum. The U.K. isn’t in the euro area, but for many populists and nationalists, Brexit suggests it’s possible to leave a coalition meant to be permanent, whether it’s a union of states or a single currency.

When his phone rang on the morning on June 24, 2011, Draghi was under no illusions about the challenges ahead. “Mario, it’s done,” said outgoing ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet. He was calling from Brussels, where the European Council had just signed off on Draghi’s appointment as the ECB’s third president.

Even before Draghi moved into his offices high up in Frankfurt’s Eurotower, the region’s debt crisis had entered a new phase, with Italy and Spain at the center of a financial-market hurricane. Bonds and stocks were plunging, and whatever liquidity was left in the interbank market was evaporating, prompting the ECB to step in and buy sovereign bonds to provide temporary relief. In a speech in Rome on July 13, the 63-year-old ECB president-to-be, who wouldn’t start his new job for another five months, set the tone for his administration: “It is now necessary to give certainty to the procedure for handling sovereign crises by clearly defining the political objectives, the instruments, and the volume of resources.”

It’s been an uphill battle ever since, but as Draghi said at Trichet’s farewell gala in October that year, “Friends tell me that I rarely shy away from impossible tasks.”

Born in postwar Rome, Draghi had learned how to handle difficult situations at a relatively young age. The deaths of his parents—his father was a banker, his mother a pharmacist—within months of each other when he was 15 left him responsible for his two younger siblings. At the time, he was attending Rome’s Istituto Massimo, a Jesuit high school that’s traditionally nurtured Italian elites. Studying under headmaster Father Franco Rozzi—a philosophy professor who demanded of his students, “Why?” whenever they came up with answers—left its mark on Draghi. “Why” remains the most frequent question he poses to his staff all these years later.

After graduating from Sapienza University of Rome with an economics degree in 1970, Draghi continued his studies at MIT. Armed with a doctorate, he returned home to pursue an academic career until then-Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti appointed him director general of the Italian Treasury in 1991. During his 10 years on the job, which required the careful balancing of the political and the technocratic, Draghi served 11 governments. A rare constant amid Italy’s political flux, he overhauled the department, led one of Italy’s largest-ever privatization drives, managed the country’s huge debt, and was instrumental in ensuring the country would be a founding member of the euro in 1999. His nickname—Super Mario—grew out of his leadership during this time.

In 2002, about a year after Silvio Berlusconi rose to power as prime minister for a second time, Draghi moved to London to join Goldman Sachs as a managing director. But by 2005 he began quietly putting out feelers for a return to public service. The next year, during the tail end of Berlusconi’s tenure, President Carlo Azeglio Ciampi called Draghi home to become governor of the Bank of Italy. (He replaced Antonio Fazio, who stepped down and was eventually sentenced to a jail term because he illegally favored a domestic bid over a foreign one in the takeover of Banca Antonveneta SpA.)

Draghi brought a touch of modernity to Palazzo Koch, the central bank’s late-19th-century headquarters, with BlackBerrys arriving on desks. He also brought his signature management style: delegation verging on aloofness. “Where’s Draghi? Elsewhere,” ran a popular office joke. After Draghi left the bank, lawmakers criticized it for failing to take Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA to task after discovering accounting anomalies in inspections that took place when he was governor. The Italian government had to spend vast sums to bail out Monte dei Paschi once the imbroglio came to light several years later. When asked by reporters in 2013 about his oversight of the troubled lender, Draghi, who wasn’t personally accused of wrongdoing, said, “The Banca d’Italia has done everything it should.”

When Italian Foreign Minister Franco Frattini started lobbying publicly for Draghi to replace Trichet at the ECB in 2009, two years before the position was due to open up, it looked like the job was destined to go to Bundesbank President Axel Weber. After all, no German had held a major European policy post since Walter Hallstein led the executive arm of the European Economic Community from 1958 to 1967.

If he were going to get the ECB job, Draghi had to overcome some obstacles. As a central bank governor, he had a seat on the ECB Governing Council. Council colleagues were irritated by his “I’m dealing with important issues, don’t bother me with details” attitude. They say his impatience and his habit of taking frequent breaks during meetings to conduct other business meant he was not as influential as he should have been considering he represented the third-largest economy in the euro area.

Back home, Draghi and Berlusconi’s finance minister, Giulio Tremonti, were barely on speaking terms as Italy sank deeper into crisis. Tremonti blamed technocrats such as Draghi for allowing the economy to go off the rails. Draghi never tired of reminding Tremonti and other politicians that it was up to them to restructure the economy, foreshadowing the line he would take with governments as ECB president. Italian politicians were outraged when Draghi co-signed a letter with Trichet demanding far-reaching reforms in Italy in exchange for ECB support.

Then, in February 2011, Weber resigned from the Bundesbank because of his opposition to an asset-purchase program, and Draghi saw his chance to go for the job. In interviews and speeches, Draghi made sure the German public was aware of his devotion to the virtues of price stability and fiscal prudence. Apparently convinced, Merkel endorsed him six weeks before the European Council vote. She expected him to run the ECB along the lines of the Bundesbank, whose tight-money policy was the blueprint for the ECB when it was founded in 1998. “He’s very close to our ideas of the stability culture and solid economic policy,” the chancellor said in a newspaper interview.

Draghi’s opening salvo as ECB president is impressive. Two rate cuts in two months reverse a policy of tightening that had prevailed earlier in the year. A series of fresh loans pump €1 trillion ($1.14 trillion) into arid markets, highlighting Draghi’s resolve to do his part in rekindling an economy that had reentered recession in the fourth quarter.

But any additional stimulus, Draghi tells the European Parliament on Dec. 1, 2011, depends on there being a “fiscal compact” among governments. The jawboning pays off, sort of. Within a week, the European Council agrees to tighter antideficit rules and a faster startup of the planned European Stability Mechanism, the euro area’s rescue fund. But Draghi wants more, so instead of stepping up bond purchases, he suspends them.

In playing hard ball, Draghi is taking his cue from Trichet, who offered him some advice during the transition period between their administrations. “I stressed very much the relationship with the heads of state,” Trichet recalls. “I told him, ‘You have to know from time to time the governments are making commitments they don’t honor.’ That was one of the many messages I had for Mario.”

The combination of economic knowledge, market savvy, and political acumen honed since his days at the Italian Treasury serve Draghi well in establishing a rapport with Merkel and other government leaders. But from the beginning his hands-off style irks ECB bureaucrats accustomed to Trichet’s micromanagement. Regular, hourlong crisis briefings introduced by Trichet disappear from the schedule, as do regular catch-up sessions with ECB directors general. Draghi’s approach: If I have a question, I’ll ask.

After his pledge at Lancaster House to do whatever it takes, Draghi returns to Frankfurt and puts his staff to work turning half-formed plans into a viable program. Some heads of government and central bankers might take Draghi to task for not having a more fully formed strategy in the first place, but not Christian Noyer, the former governor of the Bank of France who was part of Draghi’s inner circle. Draghi knew what he was doing, Noyer says: “He was relying on the capacity of the system to invent it. That’s what I call genius intuition.”

At their regularly scheduled meeting a week later, ECB Governing Council members brainstorm late into the night before all but one of them agree that they “may undertake outright open-market operations of a size adequate to” safeguard the euro. “We weren’t too far apart in our assessment of how dramatic the situation was,” Weidmann recalls. “The key difference related to the question of who’s responsible and who can fix the problem sustainably. Nobody denied that the crisis was deep.”

Even so, anything other than unanimity is a sign of trouble within the council and a clue that Germany’s worries have the potential to sway the ECB’s future path. In the years to come, Draghi and Weidmann will clash repeatedly over unorthodox policy. Breaking with tradition, Weidmann will go so far as to stand by those who later challenge the ECB in court, accusing it of overreaching its powers. Never has conflict inside the ECB run so deep.

Over time, the ECB will have to admit in Germany’s Constitutional Court that its Outright Monetary Transactions plan, announced in September 2012 as an unlimited bond-purchase program, does indeed have some limits. But this is a minor concession by the ECB. When the case comes to a close in 2015, the EU’s highest court will confirm once and for all that the ECB acted within its right and that it’s free to choose how to go about ensuring the region has stable prices and a solid currency.

Draghi’s relationship with the German public and leadership will be an aggravation throughout his term. Faced with almost constant criticism that his policies are depriving savers, making the rich richer and worsening political instability in the euro region, Draghi, a private man who doesn’t ordinarily share personal stories, seeks to calm the waters.

In an interview with the German newspaper Die Zeit, he speaks about his family history. He pursues conversations with his most outspoken critics and sends some of his closest allies out to win over those he himself can’t quite convince, such as Germany’s famously implacable finance minister at the time, Wolfgang Schäuble. The pair spar often behind closed doors, not skimping on advice about how each man should do his job. Schäuble, a veteran political scrapper, can get under Draghi’s skin like few others.

For the most part, though, the Italian keeps his mask in place. A man of few words, he is selective in choosing his company and keeps his own counsel. Critics among his ranks complain that serious discussions and arguments are no longer part of the ECB’s decision-making, replaced by prefiltered proposals from Draghi’s inner sanctum.

This is the case with the evolution of the ECB’s large-scale asset-purchase program. In April 2014, with a broad brush, Draghi sketches the premise for quantitative easing in a speech in Amsterdam. Some central bankers worry that this is the start of another go-it-alone initiative to push through controversial policy. But for now, it’s only words.

Four months later, Draghi is in Jackson Hole, Wyo., at the Federal Reserve’s annual retreat. After huddling with his staff most of one morning, he emerges to tell the world that the euro area’s inflation outlook had deteriorated—the very contingency he’d said in Amsterdam would trigger QE.

Convinced the euro probably won’t survive deflation and a third recession in a decade, Draghi sets things in motion. Trusted advisers in the world of finance are corroborating his belief that it’s about time the ECB expand its balance sheet. In Germany, the prospect of large-scale bond-buying is stoking criticism, but Draghi’s patience for the grievances of Weidmann and the broader public is running low. He speaks with Merkel regularly and is convinced she won’t stand in his way.

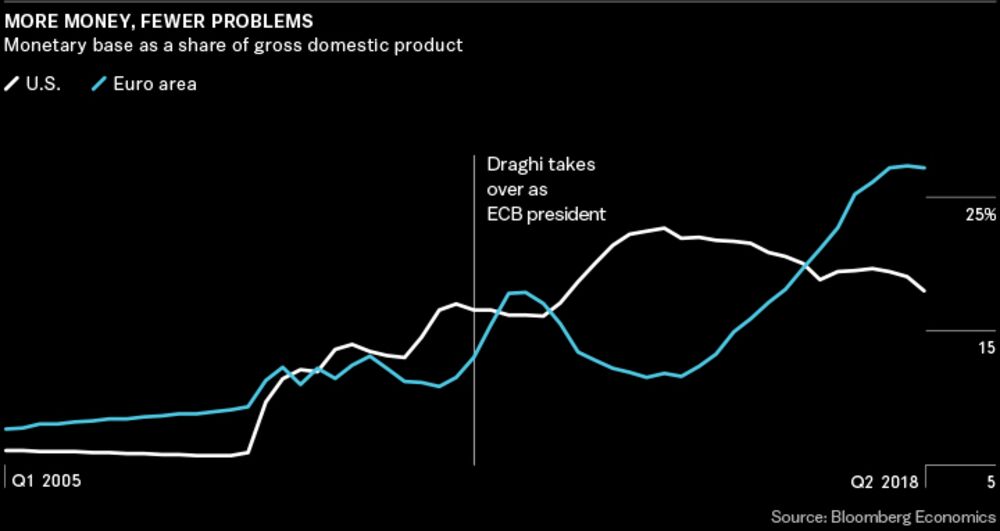

Faced with objections within the Governing Council, Draghi is willing to make compromises as long as his target, a powerful asset-purchase program, isn’t jeopardized. And so it’s agreed that any potential losses will be absorbed where they occur instead of being shared around the region, as would be general practice. In January 2015, six years after the Fed’s first round of QE, the ECB commits to an asset-purchase program that will balloon to €2.6 trillion by the time it’s due to end in late 2018. “The ECB takes a deliberative approach to easing,” says Angel Ubide, head of economics research for global fixed income at Citadel LLC. “When they do it, they do it all the way.”

The activism Draghi exhibited in the QE saga isn’t always his default response as ECB president. When Greece, the country that triggered Europe’s debt crisis in 2009, moves back into the spotlight in 2015 and a game of brinkmanship makes crashing out of the single currency a real risk, he urges a political solution. He stretches the flexibility of the ECB’s rules to keep emergency liquidity flowing to the country’s banks. Closing the tap would seal the future of Greece outside the euro, and that’s a decision Draghi isn’t willing to take.

“Draghi has the right concept about the role of governments and central banks,” says Yannis Stournaras, governor of the Greek central bank. “He believes in the power of arguments, in the power of doing the right thing. We never believed that at the end of the day, the euro would collapse.”

Draghi’s career at the ECB has been built on that premise. So has his legacy. The impact of “whatever it takes” has been felt far beyond Europe. “It inspired us to think of better ways,” says former U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, who helped oversee several QE rounds. “We were motivated by Draghi’s basically saying, ‘I assure you we are going to use every power we have to prevent the euro from blowing apart.’ I’m not sure Mario knows he was the inspiration for the design of QE3. Unlimited purchases [of bonds] were our ‘whatever it takes.’ ”

Draghi may also not know he had the ear of President Barack Obama. “Obama often asked me what Mario thought; it carried a lot of weight if I said, ‘Mario’s assessment is—’ ” says Jack Lew, Obama’s chief of staff through 2013 and then secretary of the Treasury. “Sometimes it doesn’t take personal contact to have a relationship.” Nathan Sheets, a former Fed official who was an undersecretary for international affairs in Lew’s Treasury Department, is unambiguous about Draghi’s place in history. “There’s no doubt that Draghi is the guy who saved the euro,” he says. “That’s a pretty powerful legacy.”

Draghi’s achievements on the economic front would be the envy of any central banker: The euro area, now encompassing 19 nations, is enjoying solid, broad-based economic growth; more than 9 million jobs have been created since 2013, and rising wages are finally helping people make up for the ground lost during the crisis. What’s more, the euro still exists, Greece is still part of the single currency, and the euro area is generally considered on a more stable footing than before the crisis.

Draghi regularly pronounces that the euro is here to stay. The euro, he likes to say, is “irreversible.” But is it? Or will it—like the postwar Bretton Woods exchange-rate regime—unravel at some point when European nations decide that economic, financial, and societal changes call for a different monetary order. “It’s impossible to safeguard the single currency forever,” says Clemens Fuest, president of the Ifo Institute for Economic Research in Munich. “The euro area is a currency union of sovereign states, which are free to leave at any point and maybe will. A central bank president can’t prevent that. There’s a certain fragility, which is here to stay.”

For Draghi, the breakup of the euro is unthinkable. Growing up in the shadow of World War II and having done whatever it took to safeguard the euro, he can’t imagine the dissolution of a project he believes has helped keep war at bay.

The day after he stood at the lectern at Lancaster House, nightmare scenarios about the euro seem far from Draghi’s mind. He and his wife, Maria Serenella Cappello, sit quietly and largely unnoticed among the throngs at the Olympic Stadium in London awaiting the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Games.

Soon an audience of 900 million around the world will be drawn to a celebration of great feats: the birth of the Industrial Revolution, the creation of the National Health Service, the literature of Shakespeare and Blake and Milton.

Lagarde, seated nearby, spots the Draghis and is struck by the scene. How relaxed they are, as if they haven’t a care in the world. As she would say years later, “He had just moved markets, saved the euro—and pretended he didn’t know.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.