After Dusk men from Lea Lea, a village in Papua New Guinea, wade into the Coral Sea to spear fish sleeping near the seabed. Their torches twinkle in the darkness. But they are easy to miss against the riot of illumination from a $19bn liquefied natural gas plant. Built by ExxonMobil, it stores natural gas from the country’s highlands, which is piped to tankers at the end of a jetty over a kilometre in length.

When the plant was opened in April 2014, the oil price was well over $100 and gas was similarly valuable. Energy prices have since plummeted, but Papua New Guinea’s currency, the kina, has been allowed to fall only gradually. Its strength has hurt the country’s other exports, including coffee, tourism and fish. And because foreign exchange is underpriced, the central bank has been forced to limit its availability. A decline in Papua New Guinea’s currency would, then, be a relief for many.

That sets the country apart from many developing countries, including several represented at the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (apec) summit in Port Moresby, the country’s capital, last week. Their currencies have already fallen quite enough this year, thank you. Russia’s rouble has declined by over 20% from its highest point of the year to its lowest. Other apec currencies have also suffered, including Chile’s (which declined by over 15% from its peak to its trough), Mexico’s (over 13%), and Indonesia’s (over 12%).

At the gathering Malaysia’s prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, recalled the speech he gave at the same summit 20 years ago. Back then, amid Asia’s financial crisis and Russia’s default, emerging markets were “thrown into utter disarray by currency speculators [who] were laughing all the way to the bank”, he said. But this year speculators have not had things all their own way.

Few of the big emerging markets still offer foreign-exchange traders anything resembling a one-way bet. The “extreme currency misalignments” that prevailed at the start of the year have now been largely corrected, according to the Institute of International Finance (iif), a think-tank. Better-aligned currencies have also begun to work their magic on trade imbalances. Turkey’s exports were 22% higher this September than last. Its current-account balance could turn to surplus by the end of 2018, according to the iif. In Argentina, meanwhile, falling imports helped the country post a trade surplus in September.

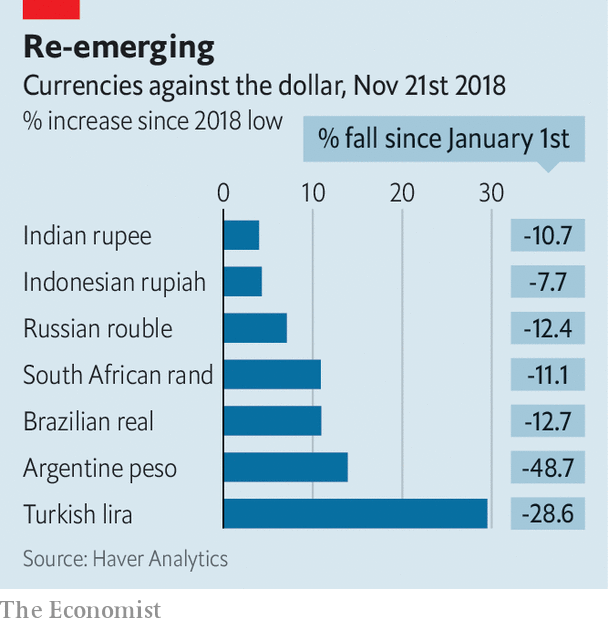

Indeed, many of the emerging-market currencies that suffered most in the summer have staged partial rebounds—enjoying a snigger, if not quite a laugh, at speculators’ expense. Turkey’s lira bottomed out in August and has since gained over 25%. The currencies of Argentina, Brazil, Russia and South Africa hit bottom the following month and have climbed substantially since. Those of India and Indonesia fell less sharply and bottomed out less quickly. But even they have eked out gains against the dollar in recent weeks (see chart).

Floating currencies can change direction as quickly as the fish in the Coral Sea. Other macroeconomic forces turn more slowly. In Turkey and Argentina, inflation and growth are still heading in an unwelcome direction. Prices rose by more than 45% in Argentina in the year to October, and by 25% in Turkey. Reining inflation in will require a painful slowdown in activity. And that is what is under way. Industrial production in Argentina fell by 11.5% in September, compared with a year earlier. Car sales in both countries are collapsing.

Elsewhere, however, inflation remains remarkably contained. In both India and Indonesia it is below 4%, and in Brazil below 5%. Cheaper oil should help reduce price pressure even further. That will weaken one rationale for hiking interest rates and thus reduce one obvious threat to growth. Taken as a group, emerging markets grew faster in 2017 and 2018 than in the two prior years, according to Capital Economics, a consultancy. The sell-off has slowed that recovery but not yet reversed it. And despite the trade war being waged by America’s president, Donald Trump, exports have been surprisingly strong.

This strength may reflect buyers of Chinese goods racing to place orders before American tariffs rise. Many emerging markets worry that if the trade war escalates, China will let its currency weaken in response, with unknown consequences for investor sentiment. The yuan may be the only major emerging-market currency that has not reached its low for the year. Testy exchanges between the two superpowers during the apec events in Papua New Guinea will have done little to calm nerves.

For the host country’s entrepreneurs, the trade war must seem an extraordinary indulgence. They face two adversaries, poverty and geography, that are more devastating than protectionism to trade. Long distances and patchy infrastructure mean that the cost of shipping local handicraft to the outside world can double the price. Crystal Kewe, a 20-year-old self-taught computer programmer in Port Moresby, won apec’s backing to launch an e-commerce site for bilum, traditional string bags in which Papuans carry infants, food and much family pride. But the cost of shipping keeps export markets out of reach for now. She aims instead to sell to tourists and other visitors, who pay to ship themselves to the product.

The bags are laden with symbolism, according to Sharlene Kylie Gawi, owner of Bilum Culture, a local bilum business. Each loop is like a member of society. Some bear a lot of weight, others less. Some threads add colour; plainer ones allow the patterns to stand out. But each loop is connected to the others. Thus described, the bags could also represent emerging markets. Argentina and Turkey have stood out this year, yet remained bound to other markets through threads of sentiment. But it is China, as ever, that carries the most weight.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.