The world is awash in debt.

While some countries are more indebted than others, very few are in good shape.

The entire world is roughly 225% leveraged to its economic output. Emerging markets are a bit less and advanced economies a little more.

But regardless, everyone’s “real” debt is likely much bigger, since the official totals miss a lot of unfunded liabilities and other obligations.

Debt is an asset owned by the lender. It has a price, which—like anything else—can go up or down. The main variable is the lender’s confidence in repayment, which is always uncertain.

But there are degrees of uncertainty. That’s why (perceived) riskier debt has higher interest rates than (perceived) safer debt. The way to win is to have better insight into the borrower’s ability to repay those loans.

If a lender owns debt in which his confidence is low, but you believe has value, you can probably buy it cheaply. If you’re right, you’ll make a profit—possibly a big one.

That is exactly what happens in a recession.

Investment-Grade Zombies

While it’s easy to point fingers at profligate consumers, households largely spent the last decade reducing their debt.

The bigger expansion has been in government and business. Let’s zoom in on corporate debt.

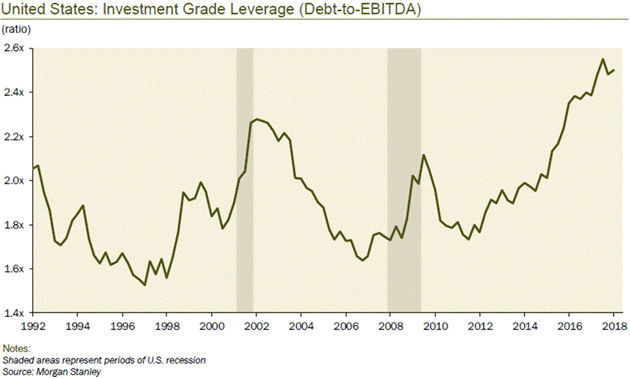

The US investment-grade bond universe is considerably more leveraged than it was ahead of the last recession:

Source: Gluskin Sheff

Compared to earnings, US bond issuers are about 50% more leveraged now than in 2007. In other words, they’ve grown debt faster than profits.

Many borrowed cash not to grow the business, but to buy back shares. It’s been, as my friend David Rosenberg calls it, a giant debt-for-equity swap.

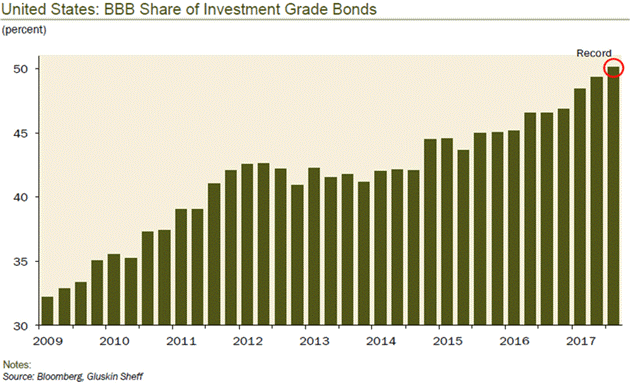

There’s another factor, though. Today’s “investment-grade” universe contains a higher proportion of riskier companies. The lowest investment grade tier, BBB, now constitutes half of all issuers:

Source: Gluskin Sheff

All these are just one downgrade away from being high-yield “junk bonds.”

The best data I can find shows that there are roughly $3 trillion worth of BBB bonds and another roughly $1 trillion worth of lower-rated bonds that would still be called “high-yield.”

If it happens like last time, the ratings agencies will wait until their fate is already sealed before they cut ratings on these zombies. But that’s only part of the problem.

Selling Under Pressure

I expect liquidity in these below-investment-grade bonds to disappear quickly in the next financial crisis.

We got a small hint of how this will look in the December 2015 meltdown of Third Avenue Focused Credit Fund (TFCVX), which had to suspend redemptions and then spend two years liquidating its assets.

The fund managers made the right call to liquidate their holdings slowly, getting the best values they could. But that won’t work if the entire fund industry is strained at the same time.

This is a structural problem with mutual funds and ETFs. They must redeem their shares on demand, usually in cash (though some reserve the right to do it in-kind).

If enough shareholders want out at the same time, this can force them to sell fund assets on short notice.

Falling Apart Quickly

When the recession hits, we will see junk bonds—and the riskier end of corporate debt generally—go into surplus.

There will be more available for sale than investors want to buy. The solution will be prices dropping to a point that attracts buyers. I don’t know where that point is, but it’s a lot lower than now.

But there’s a problem. We talked about that $3 trillion worth of BBB bonds. Any that are downgraded by merely one grade will no longer qualify as “investment grade.”

That means that many pension funds, insurance funds, and other regulated entities by law won’t be able to hold them. They have a very short time to sell them back into the market.

Let’s say company X issues $100 million of a bond rated BBB by Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s. There is a high likelihood that some will be in regulated pension or insurance funds, and there will be forced selling at lower prices.

This will set a new price for that bond issue. Every mutual fund and ETF that holds those bonds will have to use the lower price when they mark-to-market at the end of the day.

I have seen this happen three times in my career. Yields go from fairly low to 20% or more at what seems like warp speed. If you are in one of those funds, you’re going to see your value drop precipitously.

Unless you are a professional and/or have some systematic trading signal that tells you when to trade, it’s probably best to avoid anything that looks like a high-yield mutual fund or ETF.

More money is going to be lost by more people reaching for yield in this next high-yield debacle than all the theft and fraud combined in the last 50 years.

A Once-in-a-Lifetime Opportunity

I can understand the plight of retirees who are struggling to live on today’s meager yields. Those high-yield funds have been so good for so long, it’s easy to forget how disastrous a bear market can be. But it gets worse.

Quick personal story, and I have to be vague about names here.

Some bond issues have been bought in their entirety by a small handful of high-yield bond funds. The problem is that the company that issued these bonds has defaulted on them. Not just missed a payment or two, but full default.

Their true value, if the funds tried to sell them, might be 25–30% of face if they actually traded, according to the people who told me this. But the funds still value them at the purchase price of $0.95 on the dollar.

How is it they’re still valued much higher? Because the funds haven’t tried to sell them. No transactions mean they can still be “priced” at the last trade, and since there have been no subsequent trades, there is no “mark-to-market” price.

If any of those few funds sold any of these bonds, it would set a “market price” and all would have to mark down the entire holding. So naturally, they aren’t even trying to avoid taking the hit to their NAV.

So here’s my question: How many other junk bond issues are in similar positions?

Note this isn’t just high-yield funds. Lots more “conservative” bond funds try to juice their returns by holding a small slice in high-yield. Regulations let them do this, within limits, but these funds are so huge the assets add up.

This game could fall apart very quickly. Any event that triggers redemptions could set off an avalanche.

I don’t know what that event would be, but I’m pretty sure one will happen. My own goal is to be a buyer, not a seller, whenever it occurs. For now, that means holding cash and exercising a lot of patience.

If I’m right, the payoff will be a once-in-a-generation chance to buy quality assets at pennies or dimes or quarters on the dollar. I think the next selloff in high-yield bonds is going to offer one of the great opportunities of my lifetime.

In a distressed debt market, when the tide is going out, everything goes down. Some very creditworthy bonds will sell at a fraction of the eventual return. This is what makes for such great opportunities. They only come a few times in your life.

There will be one in your near future.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.