Lower oil prices could drag down U.S. shale drillers at a time when their finances are already looking shaky. But the impact on oil production growth is still murky.

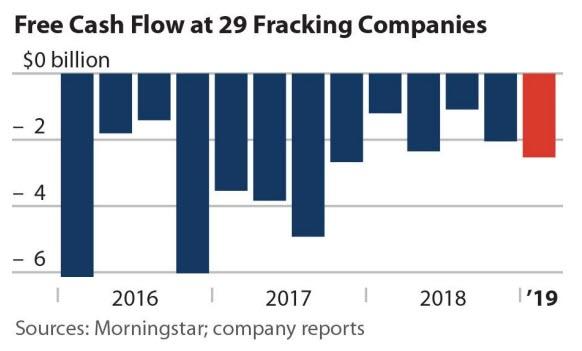

WTI is in the low-$50s per barrel, which means that the average shale driller is likely burning through cash. In the first quarter, most U.S. E&P's were cash flow negative, a period of time when WTI averaged $54 per barrel, right about where oil is trading today.

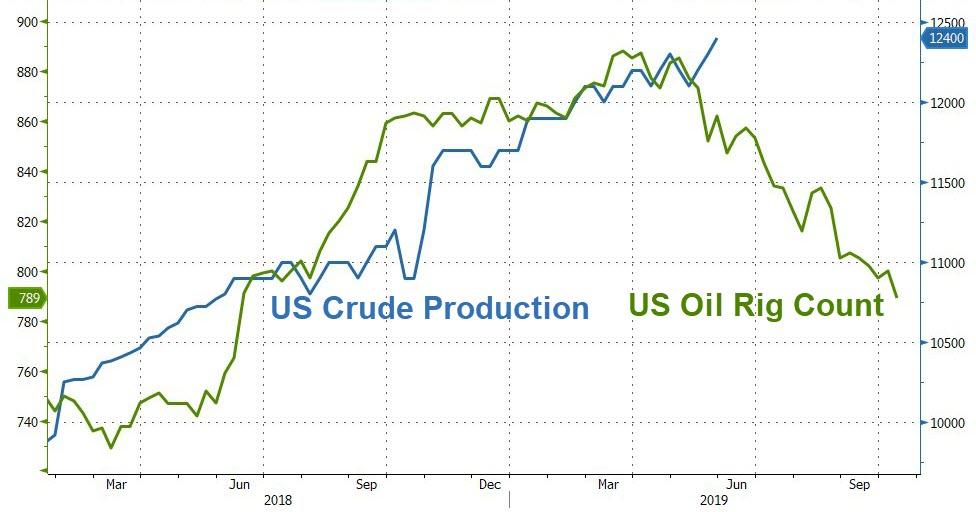

The rig count continues to fall. In the week ending on June 7, the U.S. oil rig count plunged by 11, falling to 789. The rig count has declined by roughly 11 percent, or 100 rigs, from a recent peak reached last November. In the Permian basin, where much of the action is, the rig count fell by more than 9 percent over that timeframe, from 493 to 446.

Complicating matters further for Texas shale drillers is the increasing shift of the oil slate to lighter forms of crude. Oil coming out of the ground in West Texas was light to begin with, but as drillers begin to shift increasingly from the Midland to the Delaware basin, oil is becoming lighter and lighter.

The refineries along the Gulf Coast are not equipped to handle oil that light. It is typically mixed in with other streams to create WTI, but rising volumes of ultra-light oil are forcing changes. Instead, the industry is beginning to separate out oil of different qualities, forming new grades, as Reuters reports. In addition to WTI, markets are opening up for West Texas Light (WTL) and even West Texas Condensate (WTC). These newer, lighter grades are trading for discounts, which means that some companies are selling their product for prices well below the prevailing WTI price.

But while drillers take an additional hit from discounts, the larger problem is an inability to turn a profit during virtually any period of the shale revolution. Despite years of cost-saving measures, improvements in drilling techniques and promises to lower break-even costs, the shale industry is by and large still not profitable. Investors are losing patience, and as the Wall Street Journal reports, access to capital is beginning to close off for many shale companies.

“By our math, very few oil-and-gas companies, 15% or less, can really achieve capital discipline,” Todd Dittmann, head of energy at Angelo Gordon & Co., told the WSJ.“This leaves most public companies with hope strategies and little more, hoping insufficient capital spending won’t lead to near-term production declines.”

New debt and equity issuance has dried up, forcing more asset sales in an effort to raise capital. More onerous drilling partnerships are becoming more common, in which outside investors lay claim to the returns on projects in exchange for financing a portion of the drilling. “It’s a way to keep acreage and monetize it,” Scott Sheffield of Pioneer Natural Resources told the WSJ. “It’s been a 10-year run and the equity markets are closed, and the investors want return to themselves.”

Tight-fisted investors could complicate the shale industry’s effort to grow production. But it’s too soon to tell whether or not U.S. shale will fall short of expectations. Production is still expanding, and most analysts maintain their forecasts for strong ongoing output growth. According to Kayrros, the rate of completions is still strong, which suggests that production won’t be slowing down anytime soon. Rystad Energy recently revised up its forecast for U.S. oil production to 13.4 million barrels per day by the end of this year. Moreover, even as the rig count has plunged over the last six months, production continues to rise.

But the prospect of “lower for longer” for oil prices (sound familiar?) could still lead to a slowdown. The shale industry has demonstrated an ability to grow output while not turning a profit. However, with Wall Street beginning to shut off the taps, drillers will have to do more with less.

The big question is what OPEC+ will do next, although with a bear market for oil setting in, the cloud of mystery that typically forms over Vienna this time of year has largely dissipated. The extension of production cuts is almost assured, which is why very few major oil market analysts are altering their full-year pricing forecasts. The cuts will put a floor beneath oil, even if they struggle to engineer a more rigorous rebound.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.