What do Chad Pennington, Giovanni Carmazzi, Chris Redman, Tee Martin and Marc Bulger have in common? They’re all quarterbacks, and they were all drafted before Tom Brady, who, with six Super Bowl rings, is arguably the greatest player of all-time. So how is it possible that 198 players were selected before him? Because drafting players is more art than science.

When I hear someone say “it’s more art than science,” what I really hear is “it’s at least as much luck as skill.”

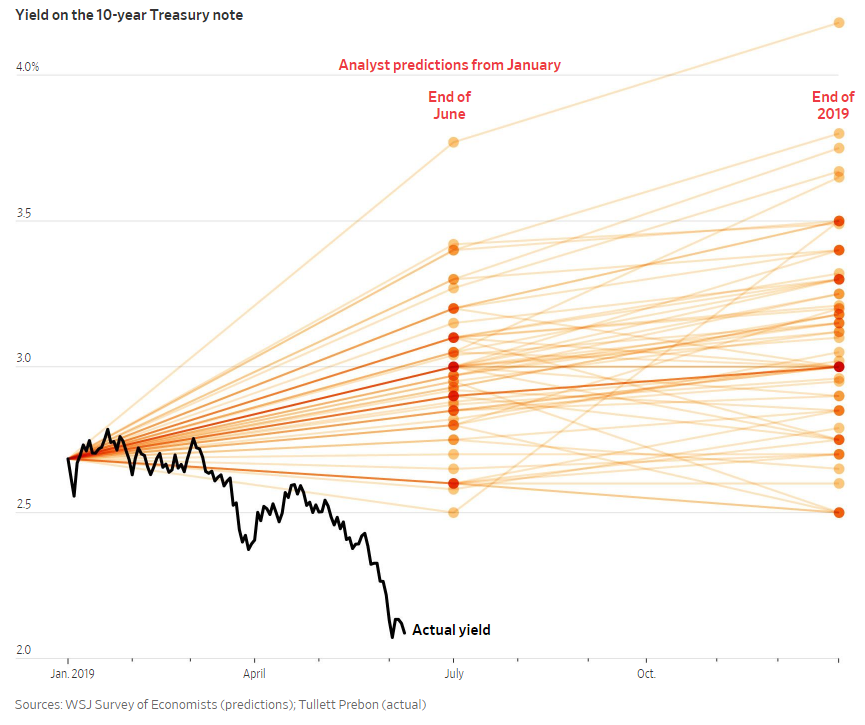

The Wall Street Journal shared an amazing graphic yesterday showing predictions from 50 economists on the direction of interest rates. The average forecast for the end of June was 3.39% on the ten-year. As you can see in the chart below, not one of them came close to where rates currently are. Economists are not dumb people, it’s just that predicting interest rates has nothing to do with intelligence; it’s more art than science.

Craig Mazin wrote The Hangover part 2 and 3, which had a combined score on Rotten Tomatoes that was significantly less than the original. He’s also the same person that wrote Chernobyl, which has the highest rating of any show ever on IMDb.

Abraham Lincoln failed in business and politics multiple times before reaching the highest office. Somebody can experience a lifetime of disappointments before they go on to achieve wonderful success. But determining whether somebody is on the verge of greatness or continued struggles is hard to quantify because it’s more art than science.

Thomas Edison once reportedly said, “I have not failed 10,000 times—I’ve successfully found 10,000 ways that will not work.” Even science can be more art than science.

Walt Disney had tremendous success in 1932 with The Three Little Pigs. It did so well commercially that he made three follow ups, none of which were able to duplicate the success of the original. He learned a valuable lesson from this and would say for years afterwards, “You can’t top pigs with pigs.” In 1934, Disney decided it was time to make his first feature film. The project took almost four years to complete and went three times over budget, so naturally, some of his backers were not too keen on his vision:

United Artists executives exhibited little enthusiasm for the project, and influential figures throughout the film industry doubted the wisdom of the Disney experiment with a feature cartoon. Walt learned that it was being called “Disney’s Folly,” and there were predictions that Snow White would sink him into bankruptcy.

In the film’s first release it grossed $8 million, which is remarkable when you consider that the average ticket price at the time was twenty-three cents.

William Goldman, author of the Princess Bride, once said, “Nobody knows anything… Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.” It’s hard to blame the executives at United Artists. The Three Little Pigs was 8 minutes long and they knew it worked. They had proof. There was no way of knowing how the audience would respond to 83 minutes, and if something isn’t broke, why fix it? Figuring out which movies will succeed and which movies will fail is more art than science.

In 1998, Larry Page and Sergei Brin tried to sell their company for $1 million. Yahoo! turned them down. It’s easy to laugh now, but it’s not like Google invented the search engine. They were the 18th company on the scene. And in 1998, there was no YouTube, no maps, and no Gmail. Predicting the future of technology is more art than science.

In Loonshots, Safi Bachal tells the incredible story of why it took the navy so long to realize what they could do with radars. The snippet below took place in 1922.

The two engineers repeated the experiment successfully several more times, and a few days later, on September 27, they sent a letter to their superiors describing a new way to detect enemy ships. A line of US ships carrying receivers and transmitters could immediately detect “the passage of an enemy vessel…irrespective of fog, darkness or smoke screen.” This was the earliest known proposal for the use of radar in battle. One military historian would later write that the technology changed the face of warfare ‘more than any single development since the airplane. The navy ignored it.

We look back on examples like this and we laugh and wonder how people could have missed something that was so obvious. I hope it’s obvious by now that things only appear obvious with the passage of time.

I was searching for something in my inbox last night when I found a conversation I had with a friend in November 2013. We were talking about two people we know who bought Bitcoin at $1,200. We were joking that it was $400. Turns out the joke was on us.

Investing, like so many things in life, is definitely more art than science. The next time you hear someone say this line, you should probably go ahead and assume they’re not Picasso.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.