Electronic banking is good news for the Indian taxman

WATCHING money drain from your bank account has never been so much fun. On WhatsApp, a messaging service ubiquitous in India, sending rupees is now as easy as posting a selfie. Set-up is a breeze, because all Indian banks have been corralled onto a common payment platform on which anyone, from Google and Samsung to local payment firms and banks themselves, can build their own user interface. Money zips instantly from one bank account to the other, without any need to set up a pesky digital wallet or download some new app. At least outside China, there is no simpler way to shift money today.

WhatsApp’s offering is being rolled out gradually. The number of transactions routed through the United Payments Interface (UPI), the system on which WhatsApp and the rest are riding, has soared from almost nothing in early 2017 to over 150m a month in January. On current trends, UPI transfers will overtake cash withdrawals from banks within weeks. Some 665bn rupees ($10.2bn) will have shifted hands—or phones—in the year to March.

All this is good news for tech-savvy Indian citizens. It is even better news for the taxman. Electronic transactions, unlike those in hard currency, leave a digital trail that makes it harder to do business informally. Just as an Uber driver cannot hide his income in the same way as a cash-in-hand cabbie can, money routed through bank accounts is easier to track, trace and tax. That is helpful because pushing more of the Indian economy out of the shadows, where perhaps half of all activity takes place, and onto the authorities’ radar has been a central policy of Narendra Modi, the prime minister.

Informality has long been the norm in India. Economists estimate that nine in ten workers toil in the grey economy (recent research from the finance ministry suggests the figure may be somewhat lower). Informal outfits, often small, employ two-thirds of all manufacturing workers, at far lower pay than in formal manufacturing jobs. The informal sector remains the employer of last resort. So Mr Modi’s claim that widespread formalisation would be akin to turning “an old civilisation into a modern society” is no overstatement.

As so often in India, data are patchy. But Mr Modi can claim some success. A new Goods and Services Tax (GST) introduced in July has boosted the number of firms registered to pay indirect taxes by 50%, to nearly 10m. This has become the most serious challenge to those looking to do business under the radar. It subsumed a plethora of nationwide and state taxes adding up to 40% of India’s total take. A sort of value-added tax, it compels businesses to declare both their purchases and their sales if they are to qualify for tax refunds. Plenty of loopholes have been built in, and lots of features have had to be delayed because of IT problems. But the miseries of implementation—and the nearly two decades of political bickering it took to get GST passed—should yield more gain than pain.

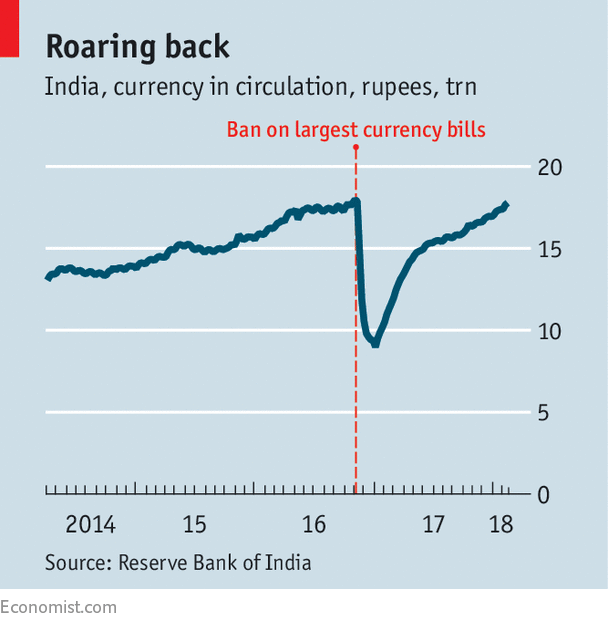

That is more than can be said for “demonetisation”, which in November 2016 compelled Indians to trade or deposit most of their cash holdings at banks before their notes turned to worthless pieces of paper. It led to the abrupt withdrawal of 86% of all bank notes from circulation. Only now is currency in circulation, which some see as a proxy for informality, creeping up to previous levels even as the economy has grown (see chart).

Saurabh Mukherjea of Ambit, an investment bank, argues that market forces have done more to nudge businesses to go formal than any government scheme has. Better infrastructure and logistics have made it easier for formal businesses to achieve economies of scale, and so to take on informal rivals whose sole competitive advantage is their ability to dodge taxes and regulation. Moderate inflation, due in part to the low price of crude oil, of which India imports oodles, has allowed for lower interest rates. That has made financing cheaper for formal firms, while informal ones have still had to make do with loans whose interest is measured in monthly, not annual, rates.The costs were clear: India’s economy slowed markedly. Fans argued, though, that it jolted India onto a new, more formal track. But if so, that track has not visibly diverged from the one it was on before. Though there was a rise in the number of Indians signing up to pay income tax, the revenue from income tax is expected to come in at 2.3% of GDP, up only a little from around 2% in previous years. Even the jump in indirect-tax registrants because of GST has led to a relatively modest increase in revenue. But at least there is a sense that dodging taxes is less acceptable in polite society than it used to be.

But whatever edge a formal business might have gained is more than undone by a thicket of labour laws that prevent small firms from growing into mid-sized or big ones, which tend to be more formal. These have barely been touched since Mr Modi came to office in 2014. The fear of being shaken down by venal bureaucrats and taxmen remains a powerful reason to stay below the radar. As a result, only one in 20 Indian workers toil in firms that employ more than 25 people, compared with around one in four in China.

Indians have everything they need to lead a formal life. Thanks to a financial inclusion drive launched by the previous government and enthusiastically continued under Mr Modi, nearly all have bank accounts. Hundreds of millions receive government subsidies for fertiliser or gas as digital payments, rather than as in-kind rations, which were often pilfered. As paying digitally becomes easier than paying in cash, India’s government should ask itself why so many citizens would still rather the authorities know nothing about them.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.