When valuations are high, the maths points to lower returns

WHEN the stockmarket is close to a record high, the chances are that recent returns will have been very strong. The terrible tendency among investors is to assume that those returns will continue. But the higher you go, the harder it is to keep rising at the same pace.

When I visited America for a story on pensions last autumn, I was struck by how few people failed to grasp this point. Public pensions have return targets of 7-8% for their portfolios. When challenged they tend to cite their 30-year record of achieving those numbers. But that record makes it less likely, not more that they will hit their targets.

The easiest way to think of this is via the bond market. In 1987 the yield on the ten-year Treasury bond was just under 9%. Since then it has fallen to its current level of just under 3%. So not only did bond investors get a high yield in their early years, they received capital gains as bond yields fell. Future returns are obviously limited by the low initial yield, but also by the small likelihood of future capital gains.

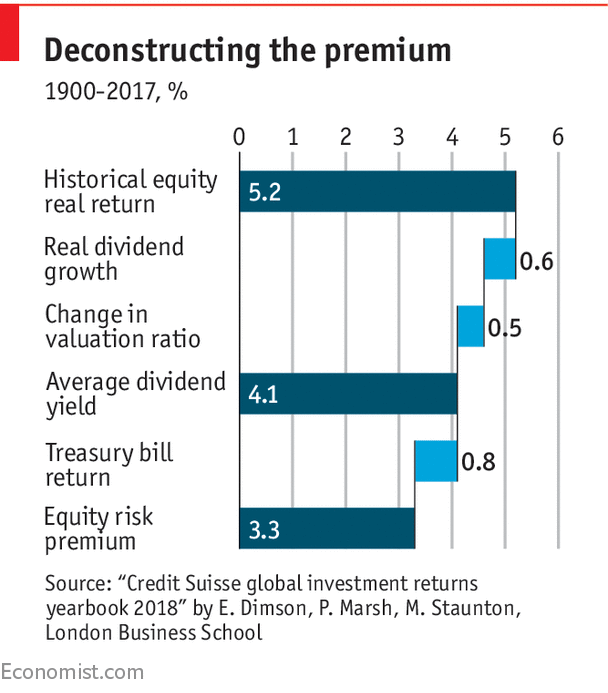

In their latest survey of long-term returns (the Credit Suisse global investment returns yearbook), Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton of the London Business School show how neatly this works for equities too. Since 1900, global investors have earned an annual 5.2% real return from equities. That reflected an average dividend yield of 4.1%, annual real dividend growth of 0.6% and a valuation improvement of 0.5% a year (see chart).

The current dividend yield on the global market is around 2.5%. It seems unwise to assume any further valuation improvement (a rise in the price/dividend ratio or fall in the dividend yield). The academics allow a fairly generous 1% for future real dividend growth to come up with a current ex ante equity risk premium of 3.5%. If that seems low, we should note that the academics made the same forecast in 2000; since then, the equity risk premium has been...3.4%.The way that academics think about returns is to say that investors get a risk-free return (from lending to the government for short periods) and then demand a “risk premium” for buying equities, which can suffer big losses in the short term. There is a difference between the ex post premium (what investors actually got) and the ex ante premium (what they expected). The LBS academics argue that investors might have hoped for real dividend growth and a valuation improvement, but they probably only counted on the dividend yield. So the ex ante equity risk premium in the past may have been 3.3%.

To estimate a total return, one must of course add the risk premium to the risk-free rate. And that is the second problem for the optimists. Real rates are negative across the world; ie short-term rates are below the rate of inflation. Even if we take a longer rate (10-year inflation-linked bonds, for example), the US has a positive real rate of just 0.5%. Adding a risk premium of 3.5% to that gets you a real return of 4%. If we assume inflation of 2%, then the nominal return from equities would be 6%. And all this assumes there is no valuation downgrade for equities, as seems quite plausible.

So even if US pension funds put their entire portfolios in equities—a highly risky strategy—they are not going to make the 7-8% they assume. This doesn’t require one to forecast a 2008-style crash, as one city finance director said to me. It is just maths.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.