Are the worst fears now priced in?

THEY make an intriguing posse: about 160 “scouts” in jeans and muddy boots, jumping out of cars with ropes in hand, plunging deep into corn (maize) and soyabean fields across the American Midwest. They are not just farmers. They include commodity traders and hedge-fund managers. Their quest: to predict this year’s harvest by using ropes as a measure and counting, to the last ear of corn and soyabean pod, the yield in a given area. “We have a really beautiful crop. I think this is going to be a record,” says Ted Seifried, a market strategist at Zaner Group, a commodities brokerage in Chicago, during a stop in Nebraska on August 21st. The mud on his boots is a reassuring sign of ample moisture in the soil.

But when he gets back into the car with others on the Pro Farmer Midwest Crop Tour, the talk turns to darker subjects, such as trade tensions, collapsing currencies and what he calls the start of an “economic cold war” between America and China. “While we’re driving the 15-25 miles from field to field, we certainly have a lot to talk about. By and large the American producer thinks the fight with China is just. But it’s very much affecting the pocketbook.”

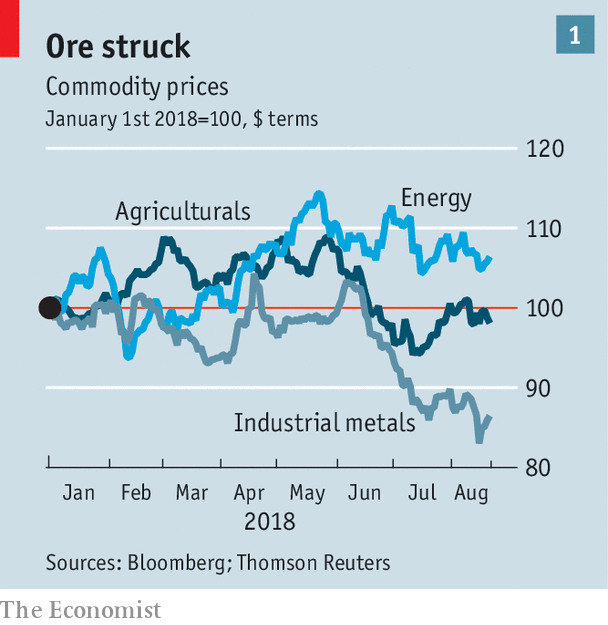

From the midwestern farm belt to the commodity markets of Chicago, New York, London and Shanghai, this is a tricky time to be producing and trading commodities. Americans may relish their stockmarkets soaring (see article). But a rising dollar, higher American interest rates, sliding emerging-market currencies and fears of a tariff-induced blow to exports to China have taken a toll on commodity prices in recent months (see chart 1).

In the background lurks climate change, fears of which have grown with the heat and drought battering Europe’s wheat crop this summer. European grain prices have surged as a result. But those of many other commodities are sagging. On August 22nd a pound of arabica coffee fell below $1, less than the cost of a takeaway brew and the lowest in 12 years. Raw sugar was also at ten-year lows. Both have been hit by oversupply in Brazil, as well as a slide in the value of the real, the Brazilian currency, which makes it more compelling to sell crops, priced in dollars, rather than store them.

The previous week, prices of copper fell into bear-market territory, down by more than 20% since June, on fears that protectionism would dampen global growth, especially in China, whose efforts to crack down on financial leverage are another drag on expansion. Oil prices have dipped for seven straight weeks, also because of concerns about lacklustre demand in emerging markets and because a strong dollar makes it dearer for those with weak currencies to buy crude. Gold has developed a strange habit of sliding in sync with the Chinese yuan.

American corn and soyabean prices, meanwhile, continue a long streak of weakness caused mainly by harvests that get more bountiful by the year. The Department of Agriculture is forecasting a record corn yield this year and the biggest harvest of soyabeans ever, something the crop tour is likely to validate, Mr Seifried says. But that is lousy timing, given that China, which was America’s biggest buyer of soyabeans, raised retaliatory tariffs on the crop in July. Farmers hope to sell more in Europe, where soyameal for animal feed is in high demand because of the high cost of wheat. But the slide in the real also makes Brazilian soyabeans more competitive.

Optimism flickers from time to time. Many commodities rallied in the run-up to the latest trade talks between American and Chinese officials, which were due to end after The Economist went to press. The dollar fell, bolstering some commodities, after President Donald Trump said in an interview with Reuters on August 20th that he was “not thrilled” with the Federal Reserve’s policy of raising American interest rates. Progress in talks on the North American Free-Trade Agreement would also be good news (see article).

But BHP, the world’s biggest miner, issued a blunt assessment of the longer-term dangers to its products during its otherwise promising year-end results on August 21st. It said protectionism was “exceedingly unhelpful” for broad-based global growth, adding that Sino-American trade tensions could weaken both countries’ GDP growth by a quarter to three-quarters of a percentage point, absent counter-measures. Both America and China imposed another tranche of tariffs, on a further $16bn-worth of each other’s goods, on August 23rd.

Analysts point to two main ways in which these tensions hurt commodity prices. The first is because of the rising importance of emerging markets to demand. In a report in June, the World Bank calculated that almost all the growth in the past 20 years in global metal consumption, two-thirds of the increase in energy demand and two-fifths of the rise in food consumption came from seven countries: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia and Turkey. This group now exceeds the Group of Seven industrial nations in consumption of coal and all base and precious metals, as well as of rice, wheat and soyabeans. Commodity prices are therefore far more sensitive to these countries’ fortunes than they used to be. Hence their walloping last week when the plunging Turkish lira gave a shock to other fragile currencies.

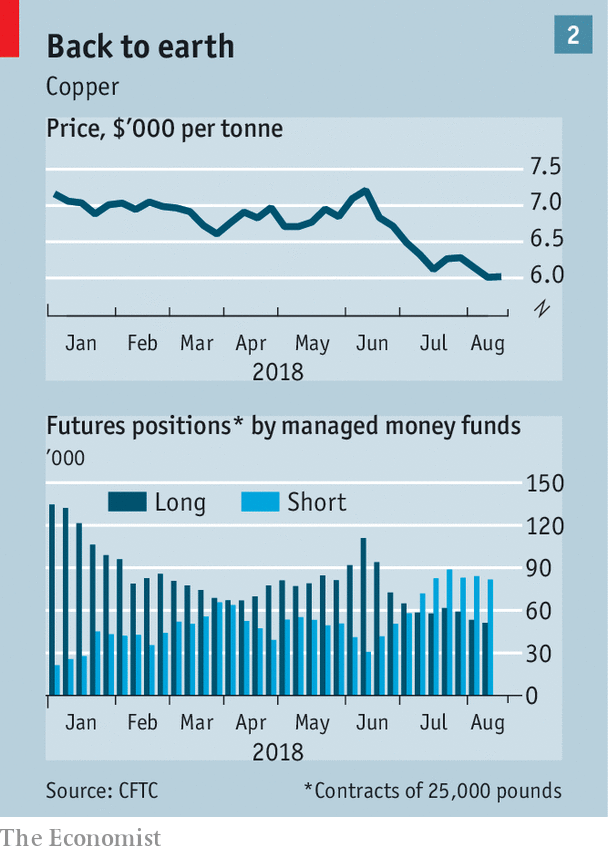

The second is speculation. Ole Hansen, head of commodities strategy at Saxo Bank, says that fears of a trade war have clobbered prices of the most globally traded commodities, notably copper, as short positions by speculators have surged (see chart 2). China accounts for half the world’s demand for copper, the same share as its consumption of steel. Yet steel prices have fared much better because the most liquid steel contract is in China, which is much more affected by domestic supply and demand factors than big global bets. A steel-futures contract in Shanghai touched a seven-year high on August 22nd.

As ever, demand from China remains the biggest swing factor for commodities. BHP reckons China will use fiscal and monetary expansion to help offset the impact to its exports from the trade conflict, which could benefit commodities. But even if the worst is now priced in, plenty of volatility lies ahead. As Mr Seifried quips from the cornfields of Nebraska, “predicting the future is a son of a bitch”.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.