Though its economic heft has declined, its surplus savings are felt around the world.

IT IS the summer of 1979 and Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, the everyman-hero of John Updike’s series of novels, is running a car showroom in Brewer, Pennsylvania. There is a pervasive mood of decline. Local textile mills have closed. Gas prices are soaring. No one wants the traded-in, Detroit-made cars clogging the lot. Yet Rabbit is serene. His is a Toyota franchise. So his cars have the best mileage and lowest servicing costs. When you buy one, he tells his customers, you are turning your dollars into yen.

“Rabbit is Rich” evokes the time when America was first unnerved by the rise of a rival economic power. Japan had taken leadership from America in a succession of industries, including textiles, consumer electronics and steel. It was threatening to topple the car industry, too. Today Japan’s economic position is much reduced. It has lost its place as the world’s second-largest economy (and primary target of American trade hawks) to China. Yet in one regard, its sway still holds.

This week the board of the Bank of Japan (BoJ) voted to leave its monetary policy broadly unchanged. But leading up to its policy meeting, rumours that it might make a substantial change caused a few jitters in global bond markets. The anxiety was justified. A sudden change of tack by the BoJ would be felt far beyond Japan’s shores.

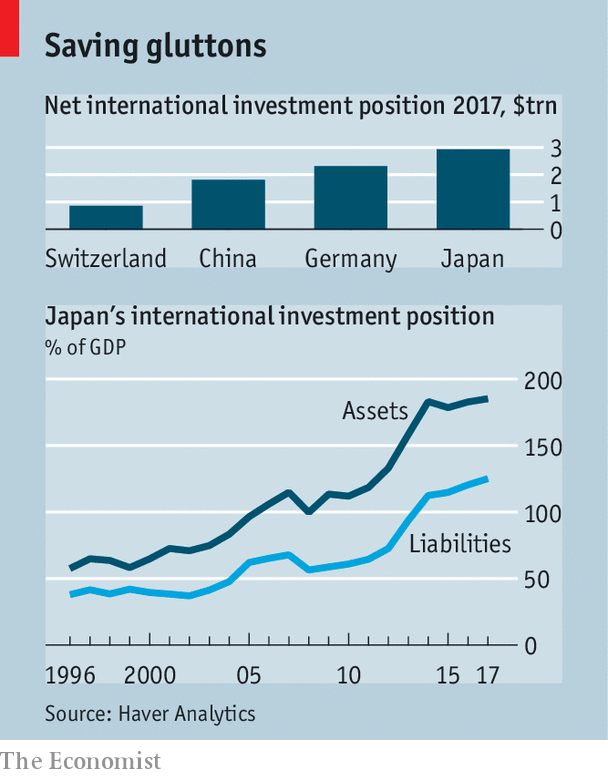

One reason is that Japan’s influence on global asset markets has kept growing as decades of the country’s surplus savings have piled up. Japan’s net foreign assets—what its residents own abroad minus what they owe to foreigners—have risen to around $3trn, or 60% of the country’s annual GDP (see top chart).

But it is also a consequence of very loose monetary policy. The BoJ has deployed an arsenal of special measures to battle Japan’s persistently low inflation. Its benchmark interest rate is negative (-0.1%). It is committed to purchasing ¥80trn ($715bn) of government bonds each year with the aim of keeping Japan’s ten-year bond yield around zero. And it is buying baskets of Japan’s leading stocks to the tune of ¥6trn a year.

Tokyo storm warning

These measures, once unorthodox but now familiar, have pushed Japan’s banks, insurance firms and ordinary savers into buying foreign stocks and bonds that offer better returns than they can get at home. Indeed, Japanese investors have loaded up on short-term foreign debt to enable them to buy even more. Holdings of foreign assets in Japan rose from 111% of GDP in 2010 to 185% in 2017 (see bottom chart). The impact of capital outflows is evident in currency markets. The yen is cheap. On The Economist’s Big Mac index, a gauge based on burger prices, it is the most undervalued of any major currency.

Investors from Japan have also kept a lid on bond yields in the rich world. They own almost a tenth of the sovereign bonds issued by France, for instance, and more than 15% of those issued by Australia and Sweden, according to analysts at J.P. Morgan. Japanese insurance companies own lots of corporate bonds in America, although this year the rising cost of hedging dollars has caused a switch into European corporate bonds. The value of Japan’s holdings of foreign equities has tripled since 2012. They now make up almost a fifth of its overseas assets.

What happens in Japan thus matters a great deal to an array of global asset prices. A meaningful shift in monetary policy would probably have a dramatic effect. It is not natural for Japan to be the cheapest place to buy a Big Mac, a latté or an iPad, says Kit Juckes of Société Générale. The yen would surge. A retreat from special measures by the BoJ would be a signal that the era of quantitative easing was truly ending. Broader market turbulence would be likely. Yet a corollary is that as long as the BoJ maintains its current policies—and it seems minded to do so for a while—it will continue to be a prop to global asset prices.

Rabbit’s sales patter seemed to have a similar foundation. Anyone sceptical of his mileage figures would be referred to the April issue of Consumer Reports. Yet one part of his spiel proved suspect. The dollar, which he thought was decaying in 1979, was actually about to revive. This recovery owed a lot to a big increase in interest rates by the Federal Reserve. It was also, in part, made in Japan. In 1980 Japan liberalised its capital account. Its investors began selling yen to buy dollars. The shopping spree for foreign assets that started then has yet to cease.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.