Spillovers through trade and banking links should be limited

IN 1546 Girolamo Fracastoro, a doctor and poet, published an elegant theory of contagion. Infections spread in three ways, he argued: by direct contact, via an intermediary, or at a distance, through the air. In medicine, his theory is now considered quaint. In economics, however, it still works pretty well.

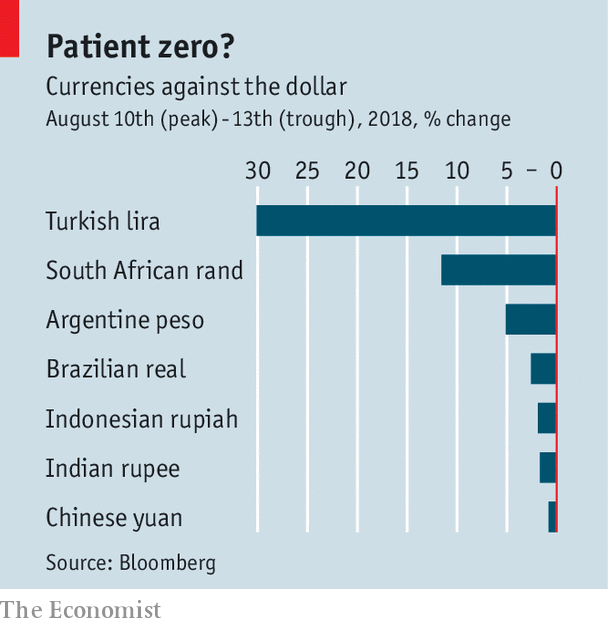

On August 10th President Donald Trump sent a pathogenic tweet, announcing a doubling of tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminium. It followed earlier sanctions on two Turkish ministers involved in detaining Andrew Brunson, an American pastor, on dubious charges. The lira, which had already lost 38% of its value since the start of the year, shed another eight percentage points in the tweet’s aftermath.

Early medical scholars believed gluttons were more susceptible to disease than cleaner-living folk. Similarly, Turkey has become vulnerable to financial disorder through macroeconomic intemperance. Businesses have borrowed heavily in foreign currencies. The government, which has manageable debt of its own, has guaranteed large amounts of private credit.

Inflation is now over 15%, far above the central bank’s target. But the monetary authority’s freedom to respond has been hampered by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s distaste for higher interest rates. The current-account deficit exceeds 5% of GDP. To fill that growing gap, Turkey relies on foreign capital inflows. But rising interest rates in America make capital harder to attract.

Turkey must now cut back. The country’s new finance minister, Berat Albayrak, who also happens to be the president’s son-in-law, says the government will strengthen fiscal discipline and narrow Turkey’s current-account deficit. Turkey’s central bank has also tightened monetary policy indirectly, suspending some of its regular auctions of cash, thereby forcing banks to borrow overnight at an interest rate higher than its declared policy rate.

The slowdown in import spending will pass some of Turkey’s sickness on to its trading partners. This is a direct form of transmission, akin to one rotten grape touching and tainting another, in Fracastoro’s analogy. The countries that export the most to Turkey, relative to their GDP, include Bulgaria, Iran and Georgia. But Turkey is not otherwise a big part of the global fruit bowl, buying 1.3% of the world’s traded goods.

Most foreign lending to the country flows through the local subsidiaries of European banks. On August 10th, reports suggested that the European Central Bank was worried about the exposure of some of the euro zone’s financial institutions. That prompted a noticeable fall in the Euro STOXX bank stock-price index. As The Economist went to press, shares of the two most exposed lenders were over 9% lower.The more worrying form of transmission is the second: via an intermediary. In Turkey’s case, the intermediaries of concern are its foreign lenders, which are also important sources of credit to many other markets.

Euro-area banks have lent about $150bn to Turkey, amounting to about 10% of their combined equity. The majority of those loans ($80bn) belong to Spanish banks, especially to BBVA, which owns half of Garanti, Turkey’s second-largest private bank. Other exposures are mainly scattered among the subsidiaries of Italy’s UniCredit and France’s BNP Paribas.

For this handful of banks, the immediate risk is that Turkish borrowers struggle to repay foreign-currency debts that are now worth much more in lira terms. Thus far, the country has relatively few non-performing loans (around 3%). But defaults are expected to rise sharply.

The infection should, however, remain minor. In a worst-case scenario, European parent banks would walk away from their local affiliates and write off the equity losses. That would cost them between 1% and 12% of group equity, according to Deutsche Bank. Such costs would certainly hurt the banks’ shareholders and perhaps oblige them to strengthen their capital buffers. But it would not threaten their solvency or require outside intervention, says Alexandre Tavazzi from Pictet Wealth Management. He thinks “the market is selling before looking at the numbers.”

That tendency to sell before looking represents the third, and perhaps most worrying, mode of transmission in emerging-market epidemiology. Fracastoro worried about “noxious air” transmitting disease across distances. Economists, mustering equal precision, worry that the dampened “spirits” of investors can transmit a crisis across countries, undeterred by the fundamental economic distinctions between them.

On August 13th, India’s rupee weakened to a record low (70 to the dollar) despite the country’s modest inflation and light foreign-currency debt. Argentina’s central bank hiked interest rates from 40% to 45% to demonstrate its commitment to stabilising prices and the peso. And South Africa suffered horrible palpitations in its currency. The rand fell by almost 10% after Mr Trump’s tweet before settling down.

But that day’s mania did not persist. Turkish regulators eased reserve requirements, giving banks greater access to the dollars on their balance-sheets, and curtailed currency-swap deals, making it harder for foreign speculators to target the lira. The government also said that Qatar will make $15bn of direct investments in the country, though the details were hazy.

The effect on Turkey’s currency was surprisingly powerful. Having traded at over seven to the dollar at the start of this week, the lira was hovering closer to six by August 15th. Global investors moved on to other worries, such as the disappointing earnings of Tencent, a Chinese tech firm that weighs far more heavily in most emerging-market investors’ portfolios than all of Turkey’s shares combined. Turkey’s crises, sadly, are more communicable than its rallies.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.