Most people expect that our signal of an impending reduction in world oil or coal production will be high prices. Looking at historical data (for example, this post and this post), this is precisely the opposite of the correct price signal. Oil and coal supplies decline because prices fall too low for producers. These producers make voluntary cutbacks because the prices they receive fall below their cost of production. There often are supply gluts at the same time.

This strange situation arises because prices must be high enough for the producersat the same time that goods and services made by oil (and other energy products) are inexpensive enough for consumers to afford. There is a two way battle taking place:

(1) Prices producers require tend to rise over time, because of depletion. The easiest to extract portion of any resource (such as oil, coal, copper, or lithium) tends to be removed first. What is left tends to be deeper, lower quality, or otherwise more difficult to extract cheaply.

(2) Prices consumers can afford for discretionary goods (such as cell phones and automobiles) tend to fall for a combination of reasons:

- Wages of many workers fall because of competition from lower cost labor in other countries.

- Some jobs are eliminated through the use of computers or robots.

- Young people are increasingly being required to pay for higher education (beyond that which is provided free), leaving many with loans to repay, reducing their discretionary income.

- Changes to US healthcare law (mostly starting January 1, 2014) lead to required health insurance premiums. While some citizens find cost savings in this approach, healthy young people often experience cutbacks in discretionary income as a result.

- Rents and home prices keep rising faster than incomes.

When the discretionary income of the many non-elite workers of the world falls, they buy fewer finished goods and services. Finished goods and services are manufactured using commodities of many kinds, including oil, coal, copper, iron ore, and fresh water. When discretionary demand falls, commodity prices tend to fall. This is the problem we are encountering now. It tends to cause the prices of many commodities to fall below the cost of production. Eventually, producers decide to quit because production is no longer profitable. This is the issue that leads to peak oil, coal or copper.

Figure 1. Illustration showing why falling affordability creates a conflict between supply and demand.

If the Affordability Price Clash Mostly Affects Non-Elite Workers, Does It Matter?

When I talk about non-elite workers, I am talking about workers who are in the bottom 90% of the wage distribution. Elite workers will always have enough income for the necessities of life. There are so many non-elite workers in the world that they, indeed, do make a difference.

Also, the forces that adversely affect non-elite workers tend to have several effects:

- They tend to send a larger share of wages to elite workers, as the economy becomes more complex and more specialized.

- They tend to send more unearned income to elite workers, through capital appreciation, because elite workers can afford to buy shares of stock and expensive homes.

- The wealthy spend their income differently from non-elite workers. Non-elite workers tend to spend the bulk of their discretionary income on devices made using commodities, such as cell phones and automobiles. The wealthy are likely to spend their discretionary income in less energy intensive ways, such as investing in shares of stock and buying services such as private college education for their children.

History shows that economies tend to collapse when wage and wealth disparity becomes too great. Collapse can take various forms, including revolutions by the disgruntled underclass, increased susceptibility to epidemics, or the financial collapse of governments. Wars become more likely, as one country tries to aid its citizens at the expense of citizens of other countries.

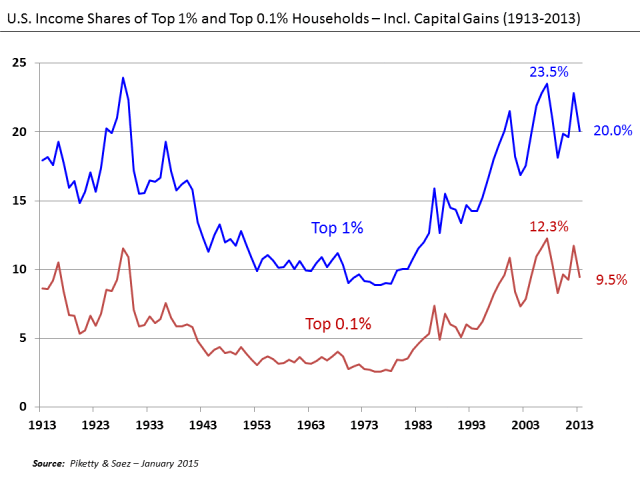

The world today seems to be approaching a crisis point with respect to wage and wealth disparity. Young people in particular are adversely affected. Figure 2 shows a chart indicating that wage disparity seems to be back to the level it was at the time of the Great Depression of the 1930s. This was also a time of low commodity prices and gluts of food and oil.

Figure 2. U. S. Income Shares of Top 1% and Top 0.1%, Wikipedia exhibit by Piketty and Saez.

Gluts tend to occur because commodity prices rise to a level where devices made with these commodities (such as cell phones and automobiles) become too expensive for non-elite workers to afford. Elite workers can still afford the devices, but there are not enough elite workers to make up for the shortfall in non-elite buyers of these devices, so industrial output per capita tends to fall.

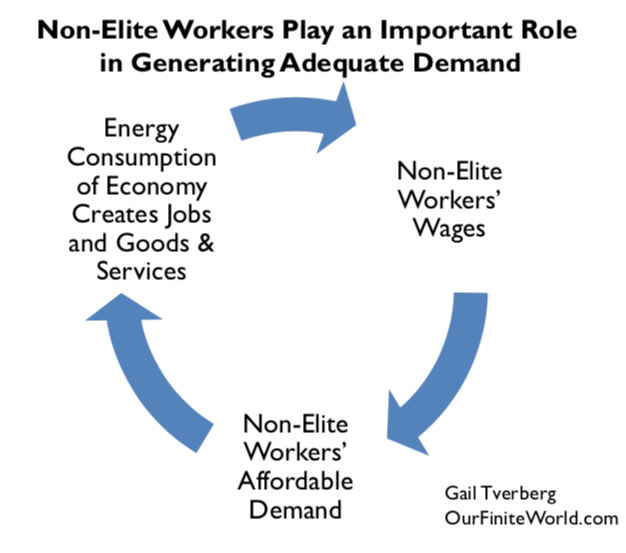

Figure 3 shows the important role that the wages of non-elite workers play in generating adequate demand. If their wages are high enough, they can buy enough goods and services made with commodities to keep commodity prices high. With sufficiently high commodity prices, production can continue.

Figure 3: Chart showing the important role that the wages of non-elite workers play in maintaining energy demand. With adequate demand, prices can remain high enough for production to continue.

Why the Peak in World Oil Production Likely Occurred in 2018

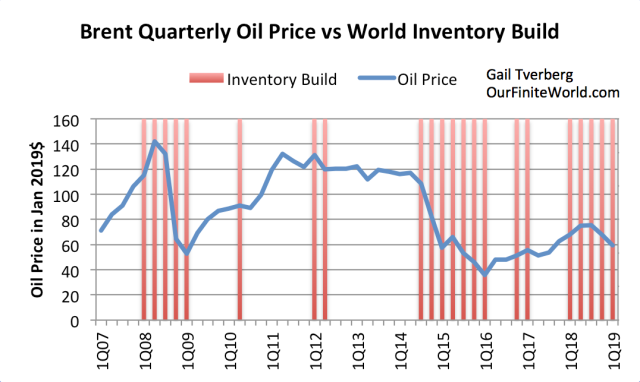

If we look at recent oil data, we see a pattern of growing gluts in supply, as indicated by the red bars in Figure 4. Even in the most recent week, the week ending February 15, 2019, after all of the cuts begun by OPEC and other oil exporters, US crude oil stocks continue to build. This is not the impact a person would expect, if the production cuts are truly effective!

Figure 4. Brent average quarterly oil price (in January 2019$), with an indication of quarters when world crude oil inventories are building. Oil prices are Brent spot oil prices, adjusted using the CPI-Urban to January 2019 prices levels. World inventory build quarters are based on indications shown in US Short Term Energy Outlook reports of various publication dates.

This is precisely the kind of signal we would expect, if products made with oil (and using oil in their operation) are becoming increasingly unaffordable for the non-elite workers of the world. Note that these bars are becoming more frequent and are occurring at lower prices. This is the expected outcome of a clash between the falling discretionary income of non-elite workers and the rising costs of oil producers.

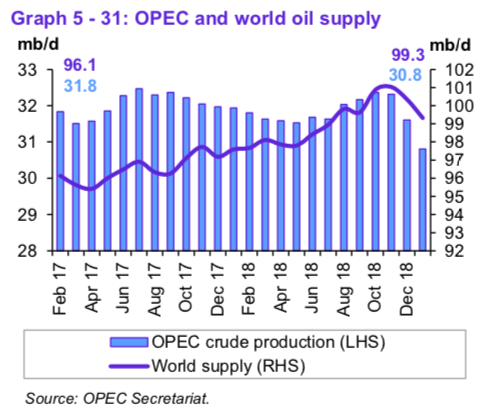

When prices fall too low, producers cut back production. OPEC reports its view of the effect of recent production cutbacks in Figure 5.

Figure 5. OPEC and world oil supply, in chart from OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report for February 2019.

Given the nearly worldwide problem of falling affordability of goods by non-elite workers, we should not be surprised if the peaks in oil production in October and November 2018 ultimately prove to be the maximum production ever recorded. In fact, it seems quite likely that the year 2018 will prove to be the year with the highest-ever oil production.

The cutback in production will appear to be voluntary. Once cutbacks start, they will tend to feed upon themselves. Unless oil prices really spike following the cutbacks (say, to $90 per barrel), exporting countries will find themselves worse off after the cutbacks, for a combination of reasons:

- The cutback in production will reduce the number of workers directly and indirectly employed by the oil industry. Their reduced spending will lead to a need for expanded government programs.

- Housing prices will fall in oil exporting countries. This is likely to ultimately lead to debt defaults.

- Tax revenue that governments of oil exporters can collect on the smaller amount of oil will be lower, even though the needs of the economy will be greater.

Ultimately, it seems likely that at least some governments of oil exporting countries will be overthrown, depressing oil production further. If the breakeven price for most OPEC members, including necessary tax revenue, was over $100 per barrel in 2014, it is hard to see how exporters can get along with much less today.

World Coal Production: Following a Similar Pattern to Oil?

One thing that most people don’t realize is that coal prices follow a very similar pattern to those of oil.

Figure 6. Sample world coal prices, based on information from 2018 BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

In Figure 6, coal prices experience a major peak in 2008, followed by a lower peak in the 2011 period, which peters out by 2013. Prices recently are much lower than in the 2008 period, or in the 2011 to 2013 period. This pattern is very similar to the recent pattern in oil prices.

The similarity in the patterns of coal prices and oil prices makes perfect sense if prices of both oil and coal are based primarily on affordability, and this affordability depends heavily on the wages of non-elite workers. When countries, such as China, ramp up their debt, more non-elite workers can be hired at higher wages. These workers can make more computers, automobiles, steel ingots, and many other goods. They can also afford to buy more output of the world economy. This ramped up demand tends to raise the prices of both coal and oil.

For many commodities, China’s demand represents close to half of the world demand. China has become the world’s number one manufacturer of goods. China needs growing energy consumption to maintain its growth of manufactured goods because it takes energy to operate machines, even computers. It even takes energy to keep the lights on.

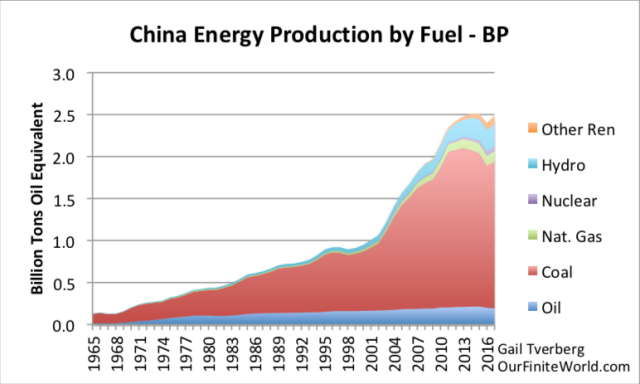

Unfortunately, with the recent lower prices for coal and oil, China is experiencing lower production of both coal and oil (Figure 7). Without growing energy supplies, China cannot meet the world’s growing need for manufactured goods.

Figure 7. China energy production by fuel, based on 2018 BP Statistical Review of World Energy data.

The reason why China has recently reduced production of both coal and oil is the usual one: the rising cost of production conflicts with the low prices available in the marketplace, making production unprofitable for a growing share of producers.

How about China’s total energy consumption? Do imports make up for China’s lack of local production?

Figure 8. China energy production by fuel, with a line added to indicated it total energy consumption, including imports. Based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018 data.

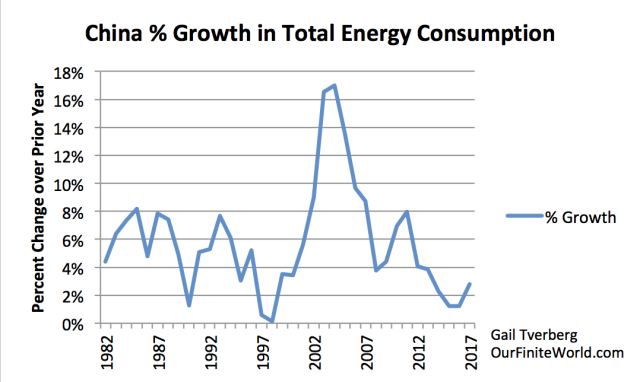

Not really. China is the world’s largest importer of coal, oil and natural gas. It is also the number one user of wind and solar (included in the tiny orange “Other Renewables” portion of the chart). Even with these huge additions to China’s energy production, its annual growth in the quantity of energy it consumes (including imports) has plummeted (Figure 9).

Figure 9. China annual growth in total energy consumption. Based on 2018 BP Statistical Review of World Energydata.

China reports that its real GDP growth rate is still very high (over 6%, net of inflation), but many observers are skeptical of this claim. Certainly, going forward, its coal and oil production cannot continue to decline, or the economy will encounter huge problems. The amount of goods China will be able to manufacture will fall, as will the number of new homes it can build. Without continued growth, China is likely to run into debt default problems. China is such a large country that its problems can be expected to adversely affect the world economy as a whole.

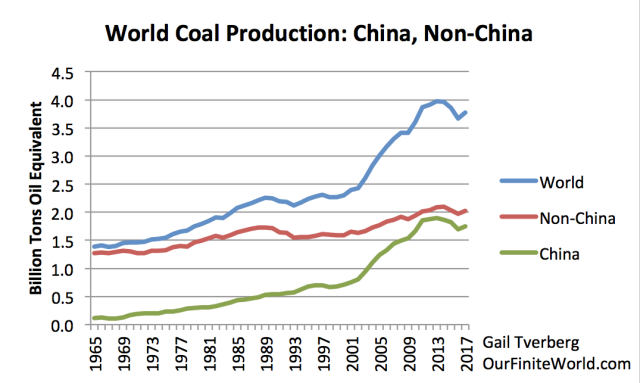

Figure 10 shows that China produces nearly half of the world’s total coal. If China’s coal production declines, world production is also likely to decline.

Figure 10. World coal production, divided into China and Non-China, based on 2018 BP Statistical Review of World Energy data.

The only way to prop up coal production, for either China or the rest of the world, is higher prices, indirectly coming from higher demand from non-elite workers. Businesses can perhaps use rising debt to hire these non-elite workers but, if there is not a sufficient supply of buyers who can afford the additional goods and services made by these workers, the final outcome will be debt defaults.

The Fundamental Problem Is a Physics Problem

The fundamental problem is that the economy grows for the same reason that hurricanes, ecosystems, stars, and plants and animals grow. They are dissipative structures that grow in the presence of energy flows. In the case of hurricanes, the energy comes from the heat in the warm ocean. In the case of the economy, the energy flows are of many different types, including (among others), human energy, energy of draft animals, solar energy, fossil fuels, and wind energy.

One key characteristic of dissipative structures is that they are not permanent. Permanent growth in a finite system is not possible. The laws of physics sets up the system in such a way that dissipative structures grow and eventually collapse. Over time, new dissipative structures form, each varying in a random way from previous dissipative structures. Those best adapted to the ever-changing circumstances tend to last the longest. This is the way that the evolution of economies takes place, just as the evolution of plants and animals takes place.

One characteristic of economies is that physics determines how much energy is needed to manufacture and transport a particular product. It also determines how much the mix of buyers can afford to pay for finished products using this energy. Thus, physics determines the potential profitability of a particular manufacturing process, with lower energy costs tending to make production more profitable. As energy costs rise because of diminishing returns, the system eventually reaches a point where it must collapse. The cost of production rises so high, relative to wages, that many non-elite workers cannot afford the finished goods and services made by the system.

The laws of physics also determine what wage distributions must look like, given the availability of energy and other resources. In general, if there are not enough resources to go around, some members of the economy tend to get “frozen out” by low wages. In addition, in a low-energy per capita situation, the energy that is available tends to rise to the top, to the high-earners of the economy, somewhat like heating water transforms it to its gas phase (steam), which rises to the top. With this structure, even with a severe energy shortfall, some members of the economy can be survivors.

With today’s worldwide economy, the survivors might be some humans and businesses within the world economy. The system would need to start over, building up smaller economies from pieces that managed to stay intact, but the system, as a whole, would not die out, unless the energy shortfall were to be severe.

Modeling the World Economy

One issue with academic research today is that it tends to be divided into many academic “silos.” Researchers tend to know more and more about their own field, but less and less about other fields that might be peripherally related. For example, economists tend not to keep up with the physics of self-organizing networked systems. Geophysicists understand the physics that governs the extraction of fuels, but they have no insight into the fact that the laws of physics might also affect prices and wage distributions.

Without understanding the forces that are causing the results that are being observed, it is very easy to create a model that is more misleading than helpful. For example, a simple model of the earth is the one each of us can see as we look around us.

Figure 11. Source: Edrawsoft.com

The model shown in Figure 11 is a flat map. This is a perfectly good representation of what the earth looks like, if a person is not concerned about what happens at a distance. Of course, to extend the map out, a person really needs to convert the model into a globe. A globe is a very different model.

Economic researchers tend to have some of the same modeling issues as illustrated by the flat map model. Economists favor fitting curves to past data to forecast the future patterns. Curve fitting tends not to be good for determining turning points. When dealing with energy and other resources, we are really interested in when a turning point will happen, forcing production of energy products and resources of many kinds downward.

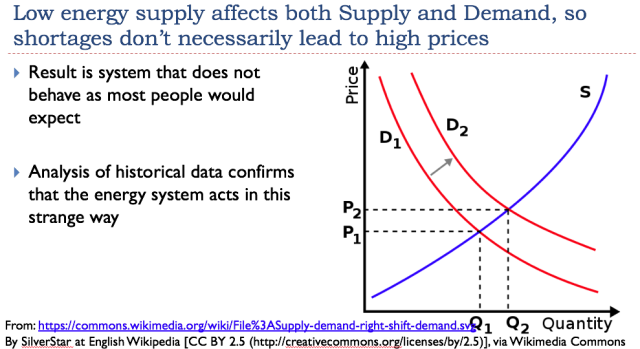

Another model favored by economists is the standard two-dimensional supply and demand model (Figure 12). This model ignores the special role that energy products play because of the operation of the laws of physics. Energy products, as they work through the networked economy, affect both the supply and demand of finished goods and services, making the two dimensional model shown inappropriate.

Figure 12. This standard model does not consider the special role energy plays in the economy under the laws of physics, so is not appropriate for energy products.

With neither curve fitting nor the standard supply and demand model sounding an alarm with respect to energy prices not being able to rise forever, economists have tended to overlook this issue.

Figure 13. Economic models tend to give a false sense of security because they forecast that the future will be a continuation of the past.

Of course, policymakers are happy to hear happily-ever-after endings. Few policymakers question the reasonableness of the models. They do not consider the possibility that the falling discretionary income of non-elite workers around the world might choke off demand for goods made with energy products.

Even geophysicists who have looked at the problem tend to get the story only half right. They understand underground physics, but they tend not to understand that prices cannot rise indefinitely. This is a different, related issue, also associated with the physics of the situation.

“Climate Change Is Our Biggest Problem” Is a Corollary to Bad Modeling

If a person truly believes that energy prices can and will rise forever, then it is an easy corollary to assume that all fossil fuels that we can identify within the earth’s crust will eventually become extractable. There are no limits except for the limits imposed by climate change.

Of course, if we are really hitting price limits here and now, the situation is likely to be very different. These price limits will cause a very near-term decline in energy supply, which we essentially have no control over. Financial systems are likely to collapse; international trade will be scaled way back; world population is likely to fall. CO2 levels will, in time, adjust to this radically changed world.

I showed earlier (in How the Peak Oil story could be “close,” but not quite right) that the models used to “prove” that wind and solar can be helpful to the system greatly overstate their benefit to the system. As a result, we don’t really have evidence that wind and solar are even helpful to the system.

Consequently, we really have two false models working together to give an illusion that we have a huge problem which is fixable, if we just exert enough effort. Physics puts a cap on our efforts, however. The physics of the system makes the system collapse before policymakers can hope to even make a small fix.

Figure 14. Two false models work together to give the illusion that climate change is the greatest problem that humans have and that we can fix the problem with fixes to the fuel system.

The unfortunate problem is that policymakers are not really in charge: the laws of physics are in charge. Energy and other resources are no longer inexpensive enough to extract to allow the system to work. The proposed solutions (wind and solar) are not cheap enough to save the system either. We can temporarily hide the problem with more debt (indirect promises of future energy) at lower interest rates, but this does not fix the system.

Conclusion

Many of the problems the world economy is facing today seem to be the result of reaching the limits of energy extraction. Very few researchers understand how a self-organized networked economy really operates. As a result, the symptoms of economic health and economic illness have been confused. It looks quite possible that we have reached both Peak Oil and Peak Coal, approximately simultaneously. This is a frightening situation, because it could be an indication of collapse in the next few years. This would likely be much worse than the Depression of the 1930s.

Of course, even with these observations, we do not know precisely what lies ahead. Somehow, multicellular animals have lived on this earth for a very long time. Amazing coincidences have happened and may continue to happen, allowing economies to flourish. We humans do not have as much control over the current situation as we would like to think that we have. Fortunately, we cannot rule out the possibility of more amazing coincidences, perhaps even caused by a literal Higher Power behind the energy flows. Thus, the result may be different from what our models seem to suggest.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.