In China’s manufacturing heartland, Donald Trump’s trade war has had less of an impact on the labor market than the lure of easier, better paid jobs in the nation’s booming services industry.

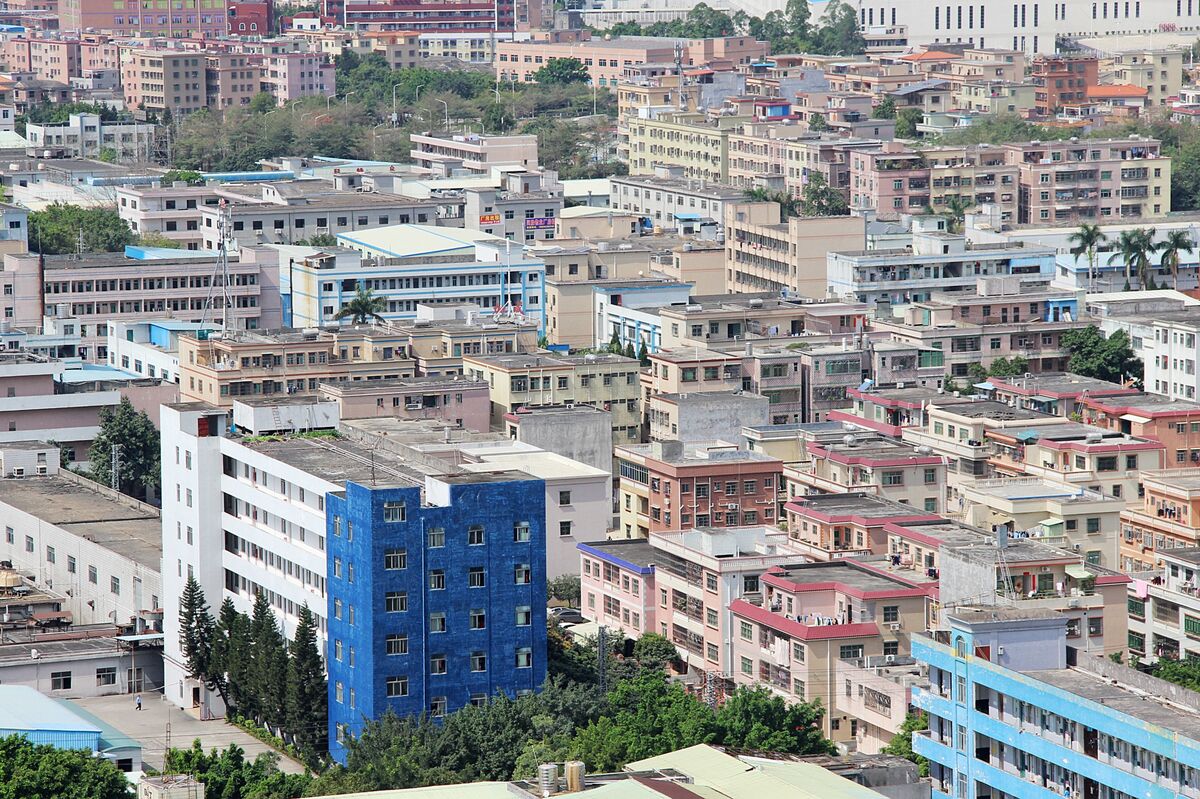

At a plastic factory in the city of Dongguan, the recruiting manager says that it’s the most difficult hiring year in two decades. An electronics firm is losing employees to package couriers in the same neighborhood. Executives are trying to coax manpower to the assembly lines with wage increases, one-off referral bonuses, and are even combing inland villages for would-be workers.

The evidence, gained from interviews with 20 managers in the southern city, conducted during the busy hiring season following Chinese New Year, suggests that the nation’s labor market is still robust, despite the economic slowdown.

Yet their responses also signal some of the pressures ahead for the manufacturing sector, grappling with Trump’s tariffs, rising domestic wages, and the slow bleeding of competitive advantage to neighboring countries like Cambodia and Vietnam.

“Package delivery, food delivery and online stores have all absorbed many workers who would otherwise have come to us, said Wu Huaquan, a recruiter at Dongguan Sumida (Taiping) Electric Co., which makes electronic components for mobile phones. “The services sector is sending huge shocks to the factories.”

On the face of it, the impact of Trump’s tariff war has been manageable so far. The higher 25 percent tariffs have not been imposed, and exports to the U.S. reached a record last year. A deal to manage the standoff is reportedly near.

No Slack

The official jobless rate has barely budged as the economic slowdown deepened, hovering around 5 percent throughout 2018. Wage restraint, and the growing number of jobs available outside the manufacturing sector have helped.

“We have not seen any slack overall across the country,” said Helen Qiao, chief Greater China economist at Bank of America Corp. in Hong Kong. “When the Chinese economy is in a downturn and hiring demand slows, you might see slower wage increases, but not necessarily substantial pay cuts or mass lay-offs,” she said.

The added pressure from the trade war has helped highlight the challenges facing factory managers in Dongguan, a 90-minute drive from the Hong Kong border. Profitable factories can offer salary inducements, whereas firms with tighter margins are facing closure or relocation, testing the ability of the rest of the economy to absorb laid-off workers.

Online Boom

Online shopping and delivery services have boomed in China in recent years, with more and more people needed to deliver food and merchandise for companies like Alibaba Group Holding Ltd and Meituan Dianping. The express delivery sector alone hired more than 1 million people in 2017.

Manufacturing in general is under pressure, in China as elsewhere in the global economy. The official China manufacturing PMI has been below the 50 mark that denotes contraction since November.

Wu Huaquan’s factory output, electronics, has been hurt by the tariff war, though he says his firm has been able to expand market share by making better products and cutting prices.

Inland Hunt

Wu hired about 500 workers this spring by offering them 9 percent more than what he paid last year -- costing millions of yuan a month that many competitors couldn’t afford. “Other factories hate us because we scooped their workers,” he said.

That was echoed by He Wenyue, a recruiter for Dongguan Ruyi Clothing, which offered a 10 percent to 20 percent salary increase and said the company may have to automate more production or relocate to cheaper places. Mr. Peng at toy maker Yingfeng Plastic & Electronics Products, plans to go further than waiting for people to come to his gate. "We’ll go directly to remote villages in inland areas," said Peng, who only gave his last name, adding that he plans to collaborate with the officials there.

Yet despite the labor shortage, almost half of the managers said they are not offering a pay increase, citing wafer-thin profits. Overall wage inflation across the manufacturing sectors as well as the overall economy will be 2 to 3 percent this year, according to Li Qiang, executive vice president at Zhaopin Ltd, an online recruitment platform.

Even with those modest wage gains, much of the lower end of China’s manufacturing sector is facing growing pressure to relocate to places with dramatically lower costs, either inland or elsewhere in Asia.

After losing many workers last year, Hongding Leather Goods is not close to filling the 60 openings this spring, according to operational manager Zhang Guojun, and the firm isn’t hiking wages either. Exporting most of the leather belts they make to the U.S., Zhang was worried about the trade war throughout last year.

“The factory needs to stay open and we are just getting by," Zhang said. "We don’t have any options.”

Policy makers are working to help firms like Zhang’s. Premier Li Keqiang this week announced an “employment first” policy, and the top economic planning body said it will prioritize supporting firms affected by the trade tensions and stabilize jobs there. For Zhang though, those policies might be too late.

His company is, in fact, building a factory in Cambodia, and has been recruiting 2,000 workers since September. “We don’t need to worry about the tariffs there, and the workers aren’t that expensive.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.