Robots are hiding in plain sight. It’s time we stop ignoring them.

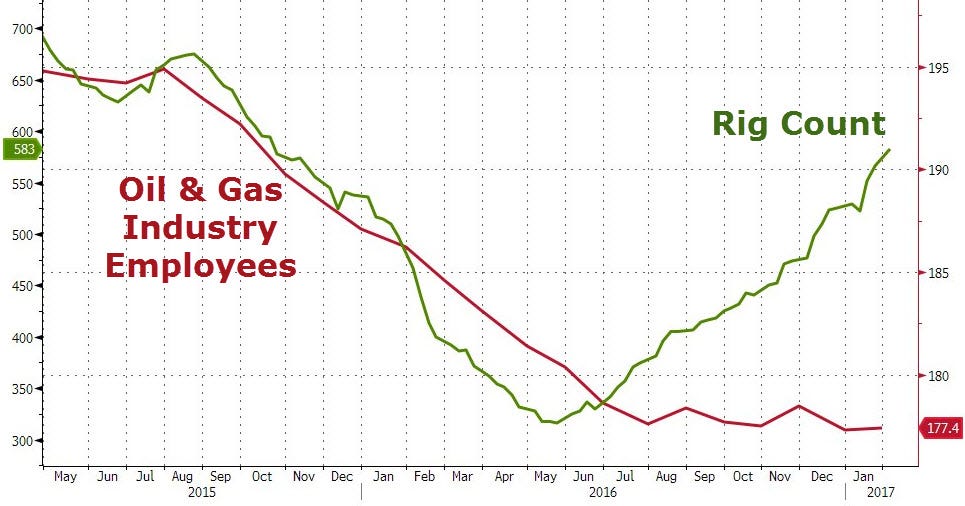

There’s a chart I came across earlier this year, and not only does it tell an extremely important story about automation, but it also tells a story about the state of the automation discussion itself. It even reveals how we can expect both automation and the discussion around automation to continue unfolding in the years ahead. The chart is a plot of oil rigs in the United States compared to the number of workers the oil industry employs, and it’s an important part of a puzzle that needs to be pieced together before it’s too late.

What should be immediately apparent is that as the number of oil rigs declined due to falling oil prices, so did the number of workers the oil industry employed. But when the number of oil rigs began to rebound, the number of workers employed didn’t. That observation itself should be extremely interesting to anyone debating whether technological unemployment exists or not, but there’s even more to glean from this chart.

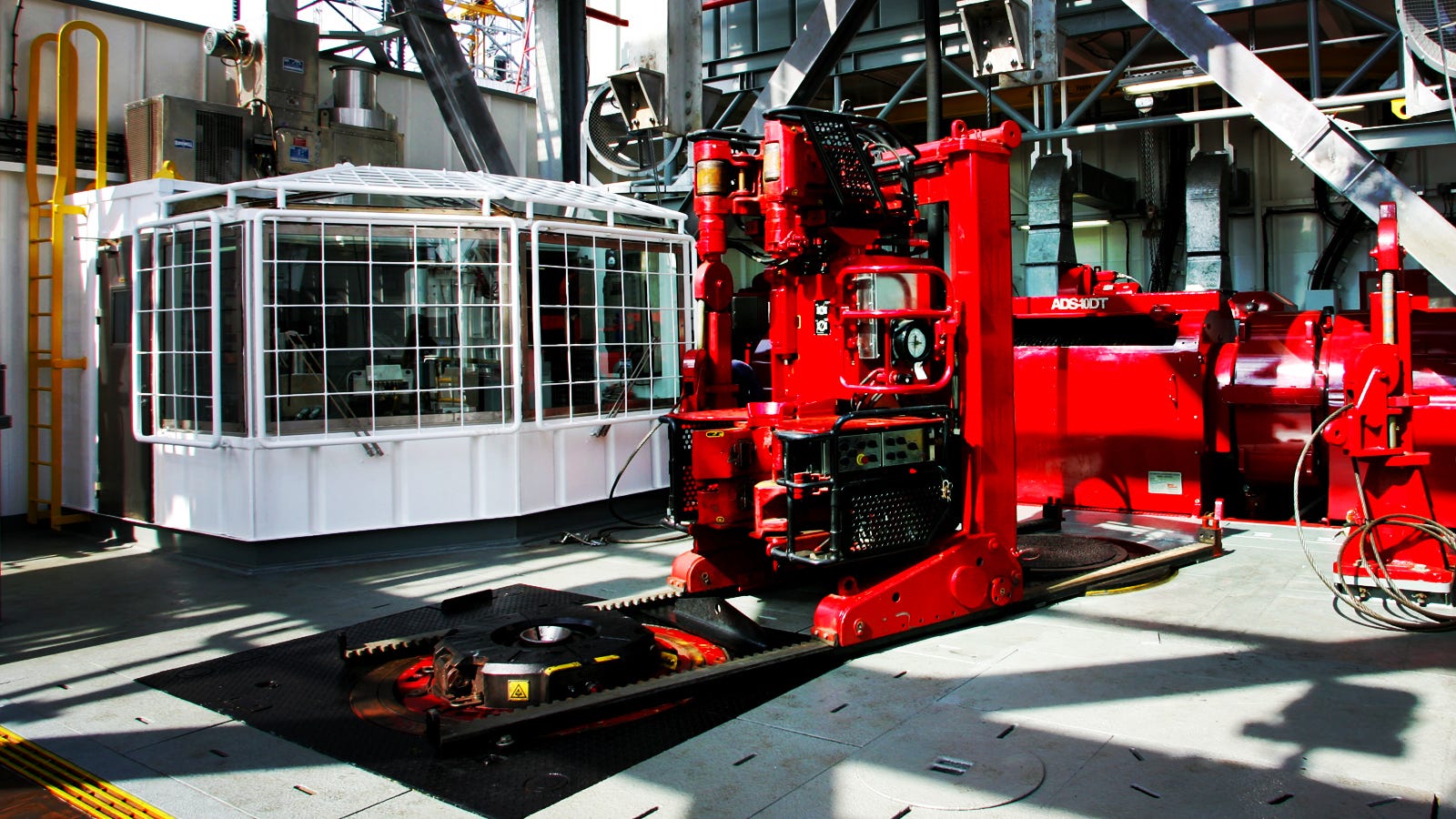

First, have you even heard of automated oil rigs, or are they new to you? They’re called “Iron Roughnecks” and they automate the extremely repetitive task of connecting drill pipe segments to each other as they’re shoved deep into the Earth.

Thanks to automated drilling, a once dangerous and very laborious task now requires fewer people to accomplish. Automation of oil rigs means that one rig can do more with fewer workers. In fact, it’s expected that what once took a crew of 20 will soon take a crew of 5. The application of new technologies to oil drilling means that of the 440,000 jobs lost in the global downturn, as many as 220,000 of those jobs may never come back.

Now look back at the chart again, and notice how quickly this all happened. It took TWO YEARS. How did it happen so fast? Because the oil industry didn’t really need the workers it lost in the first place. It’s the oil industry. It’s used to making lots of money, and when you’re making money hand over fist, you don’t need to focus on efficiency. Being lean and mean is not your concern. However, that changes when times get tough, and times got very tough for the oil industry as oil prices plummeted thanks to new competition from yet another technological advancement — fracking.

So once it became important to increase efficiency, that’s exactly what the oil industry did. It let people go and it invested in automation. In the summer of 2016, oil prices were no longer under $30 per barrel, and had gone back up to around $50 per barrel where they remain. That’s half of the $100 per barrel they’d gotten used to, which is fine as long as they’re able to produce at twice the efficiency. As a result, like a phoenix rising, they emerged transformed. Oil rigs returned to drilling, but all the rig workers didn’t. Those who were let go became simply unnecessary overhead.

Sleeping Through a Wake Up Call

This is a story of technological unemployment that is crystal clear, and yet people are still arguing about it like it’s something that may or may not happen in the future. It’s actually a very similar situation to climate change, where the effects are right in our faces, but it’s still considered a debate. Automation is real, folks. Companies are actively investing in automation because it means they can produce more at a lower cost. That’s good for business. Wages, salaries, and benefits are all just overhead that can be eliminated by use of machines.

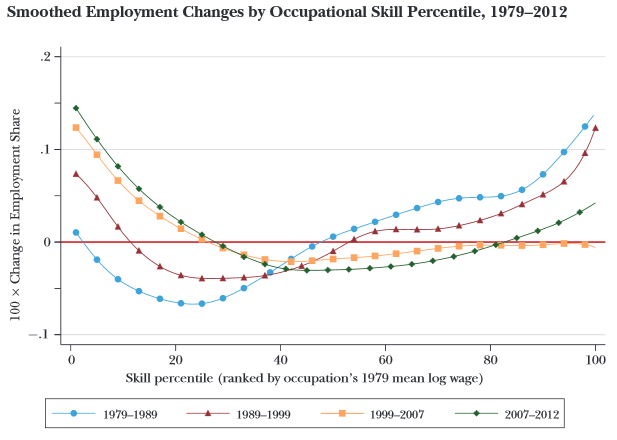

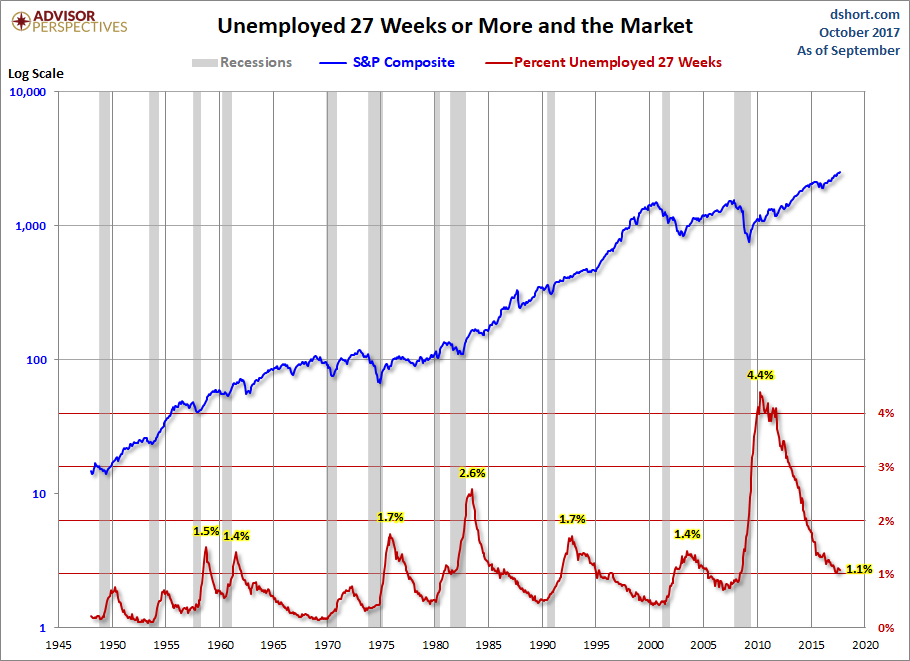

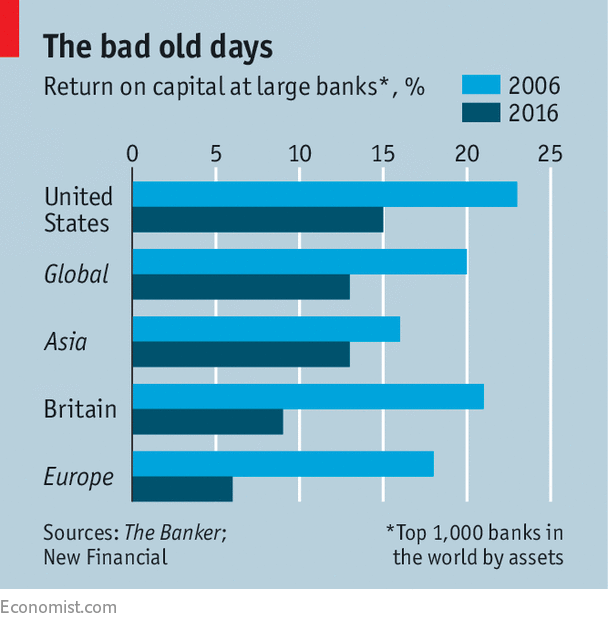

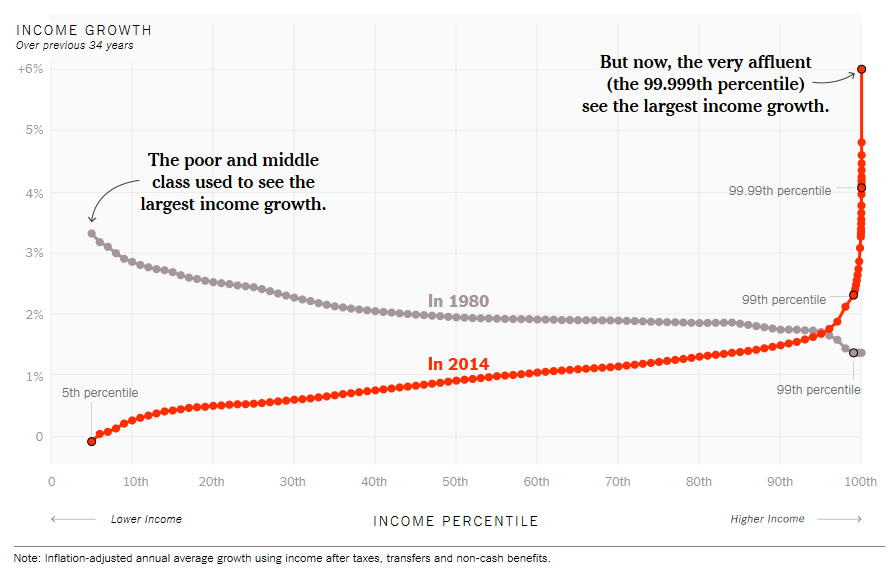

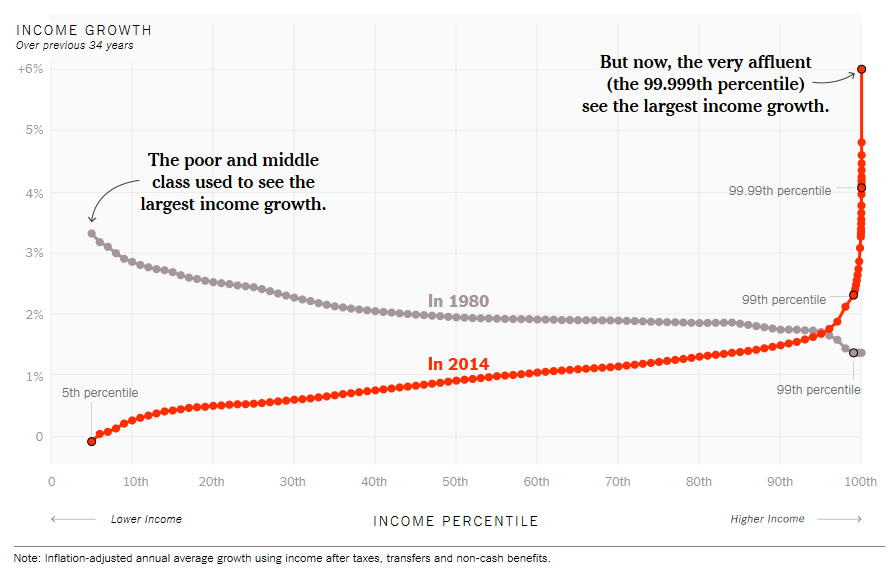

But hey, don’t worry, right? Because everyone unemployed by machines will find better jobs elsewhere that pay even more… Well, about that, that’s not at all what the history of automation in the computer age over the past 40 years shows. Yes, some with highly valued skills go on to get better jobs, but they are very much the minority. Most people end up finding new paid work that requires less skill, and thus pays less. The job market is steadily polarizing.

Decade after decade, medium-skill manufacturing/office jobs have been disappearing, and in response, the unemployed have found new employment in new low-skill service jobs. People unemployed by machines still require income, so they end up finding what they can get. At the same time, they are competing against others doing the same thing (as long as the labor market remains involuntary) and thus people are bidding down their own wages and taking any job they can get in a race against the machines. This also serves to make investments in automation less attractive. As an added bonus, the jobs that are being automated are more productive jobs than most of the jobs being newly created. Cheaper human labor and an increasing number of low productivity jobs together then result in a “paradoxical” deceleration of productivity growth. Long story short, the middle of the labor market is disappearing. That’s the reality, and it’s been happening for decades.

A landmark 2017 study even looked at the impact of just industrial robots on jobs from 1993 to 2007 and found that every new robot replaced around 5.6 workers, and every additional robot per 1,000 workers reduced the percentage of the total population employed by 0.34% and also reduced wages by 0.5%. During that 14-year period of time, the number of industrial robots quadrupled and between 360,000 and 670,000 jobs were erased. And as the authors noted, “Interestingly, and perhaps surprisingly, we do not find positive and offsetting employment gains in any occupation or education groups.” In other words, the jobs were not replaced with new jobs.

It’s expected that our industrial robot workforce will quadruple again by 2025to 7 robots per 1,000 workers. (In Toledo and Detroit it’s already 9 robots per 1,000 workers) Using Acemoglu’s and Restropo’s findings, that translates to a loss of up to 3.4 million jobs by 2025, alongside depressed wage growth of up to 2.6%, and a drop in the employment-to-population ratio of up to 1.76 percentage points. Remember, we’re talking about industrial robots only, not all robots, and not any software, especially not AI. So what we can expect from all technology combined is undoubtedly larger than the above estimates.

Automation has been happening right under everyone’s noses, but people are only beginning to really talk about the potential future dangers of automation reducing the incomes of large percentages of the population. In the US, the most cited estimate is the loss of half of all existing jobs by the early 2030s. It’s great that this conversation is finally beginning, but most people have no idea that it’s already happening. And about half of those people who know it’s happening, are relying on magical thinking to support their beliefs that automation is of no concern. To the contrary, it is of massive concern.

Charting the Course of History

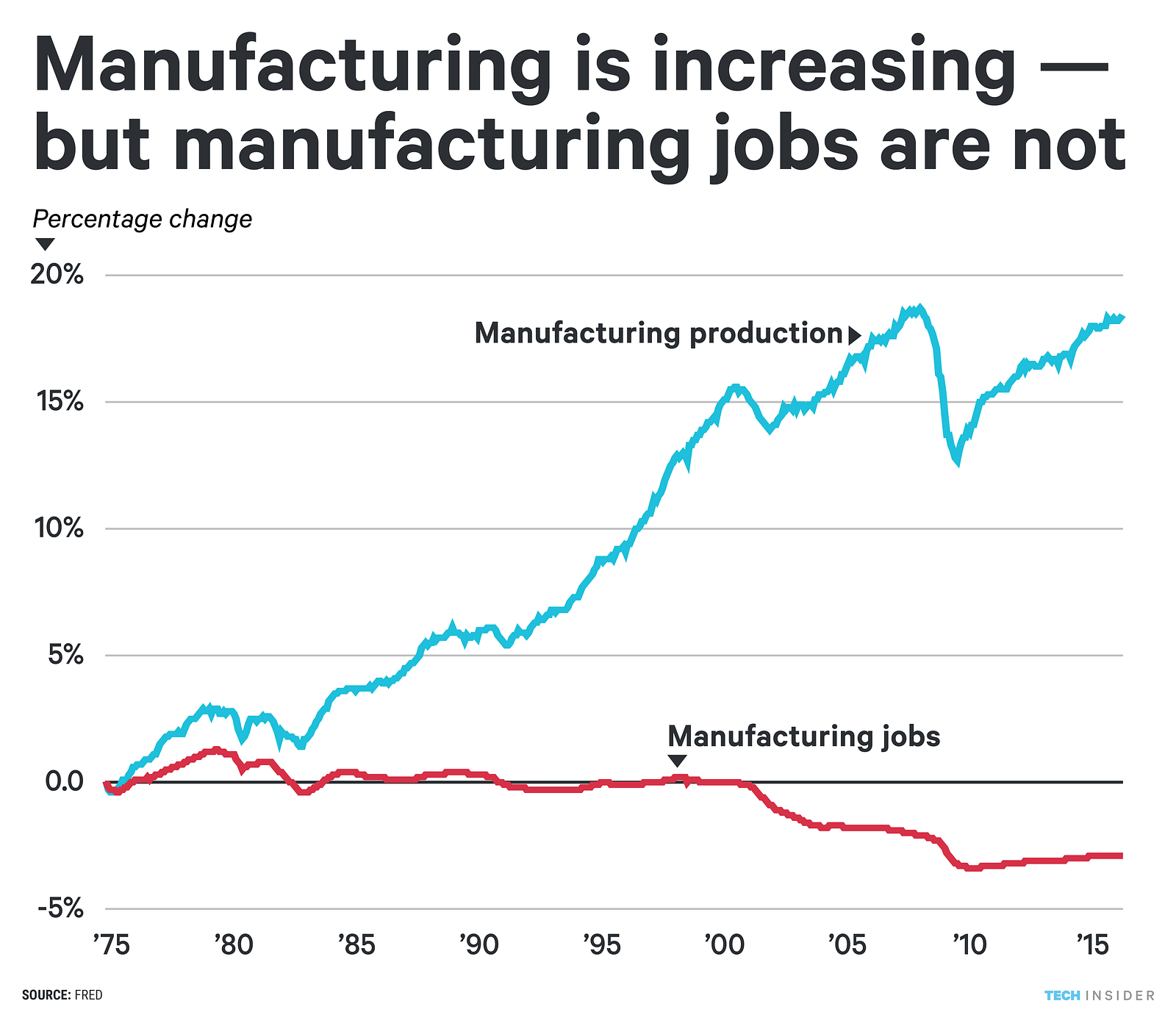

One of the most telling statistics I’ve come across in regards to the automation discussion is how almost everyone in the US knows we’ve lost manufacturing jobs over the past three decades. 81% know that very real fact according to a poll of over 4,000 adults by Pew Research. What few people know however is that at the same time the total number of jobs has decreased, total manufacturing output has increased. The US is manufacturing more now than it ever has, and only 35% of the country knows that’s true. The percentage of Americans who know both of the above facts are true is a mere 26%.

Only one out of every four Americans knows that thanks to technology, we’re producing as a country far more with less. Most people don’t know that, or blame things like immigrants or offshoring for job losses, even though offshoring is only possible due to technology improvements and only accounts for 13% of manufacturing job loss. That’s a problem. We can’t make the changes we need to make if people aren’t aware the problem exists, or think the existence of the problem is something to be debated. We can’t agree on solutions like unconditionally guaranteeing everyone a basic income as a rightful productivity dividend if people are actively being unemployed by growing productivity and the discussion is framed as a future danger to our social fabric instead of a clear and present danger.

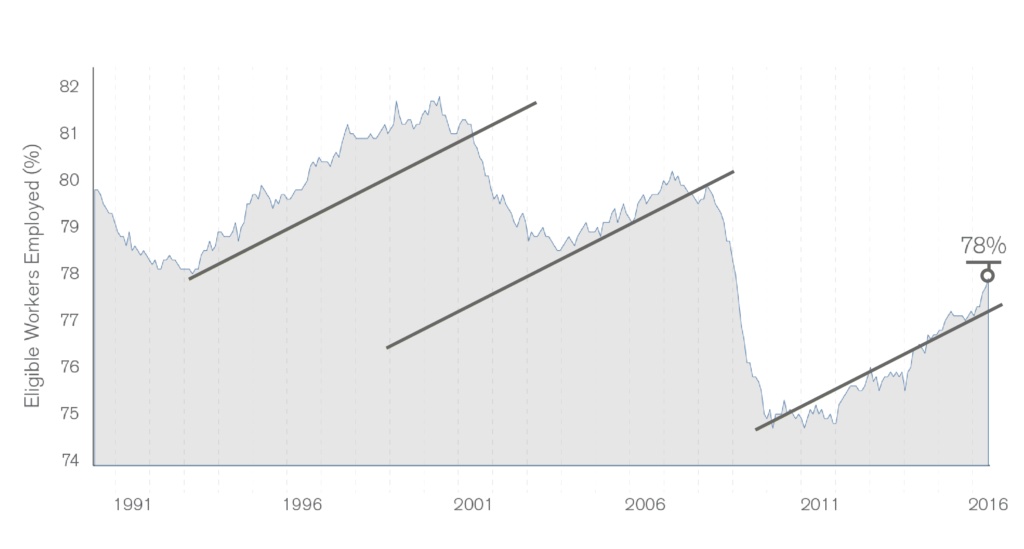

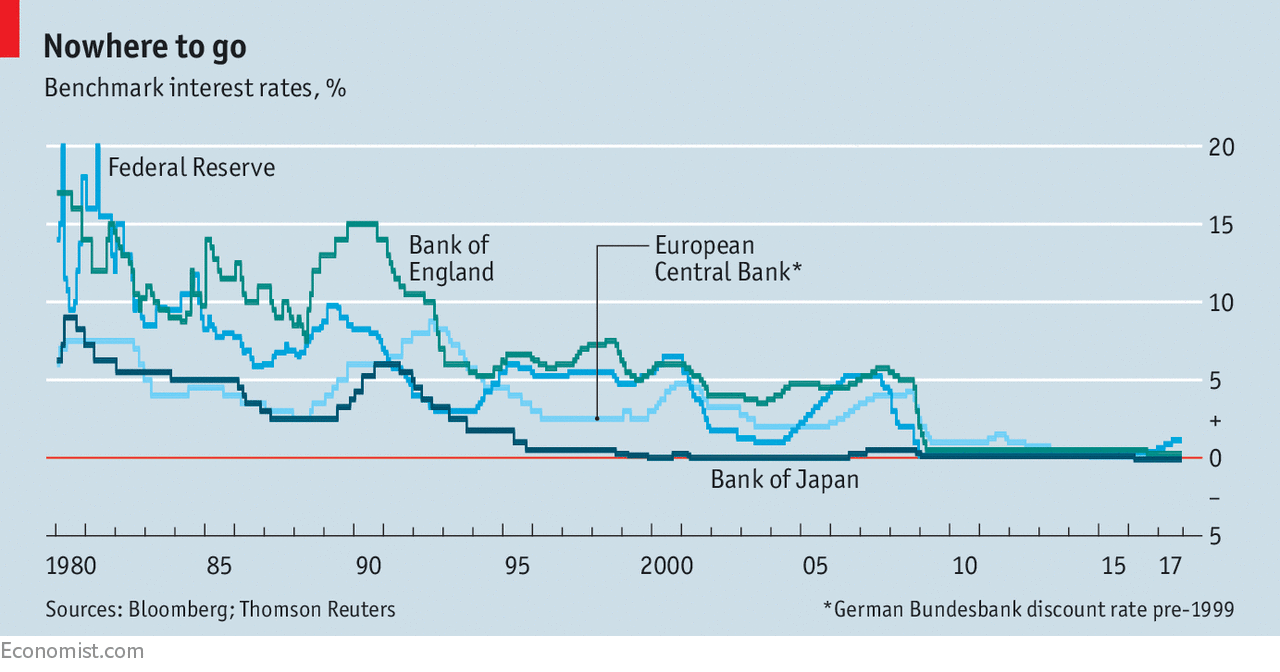

Consider this: What happens when the next recession hits? Falling oil prices simulated a recession in the oil industry, which responded with mass unemployment and investment in automation. What happens when allindustries respond with mass unemployment and investments in automation? If we look at recent history, each successive downturn has resulted in the permanent shrinkage of the labor market. Peak labor appears to have already occurred back in 2000.

Meanwhile, technology is only getting cheaper, so each successive drop squeezes out more human labor, and is able to automate more lower-skill labor that is newly more expensive than machines. Expect the next recession to put over ten million of people out of work, and for the economy to realize they didn’t really need those people as workers after all to produce what was being produced. Where 79% of eligible workers aged 25–54 were employed, expect that to fall to 69% or below. The economy simply doesn’t need the number of people it currently employs with the technology we already have available. To add insult to injury, it’s taking longer for the unemployed to find employment, so those suffering next will suffer longer.

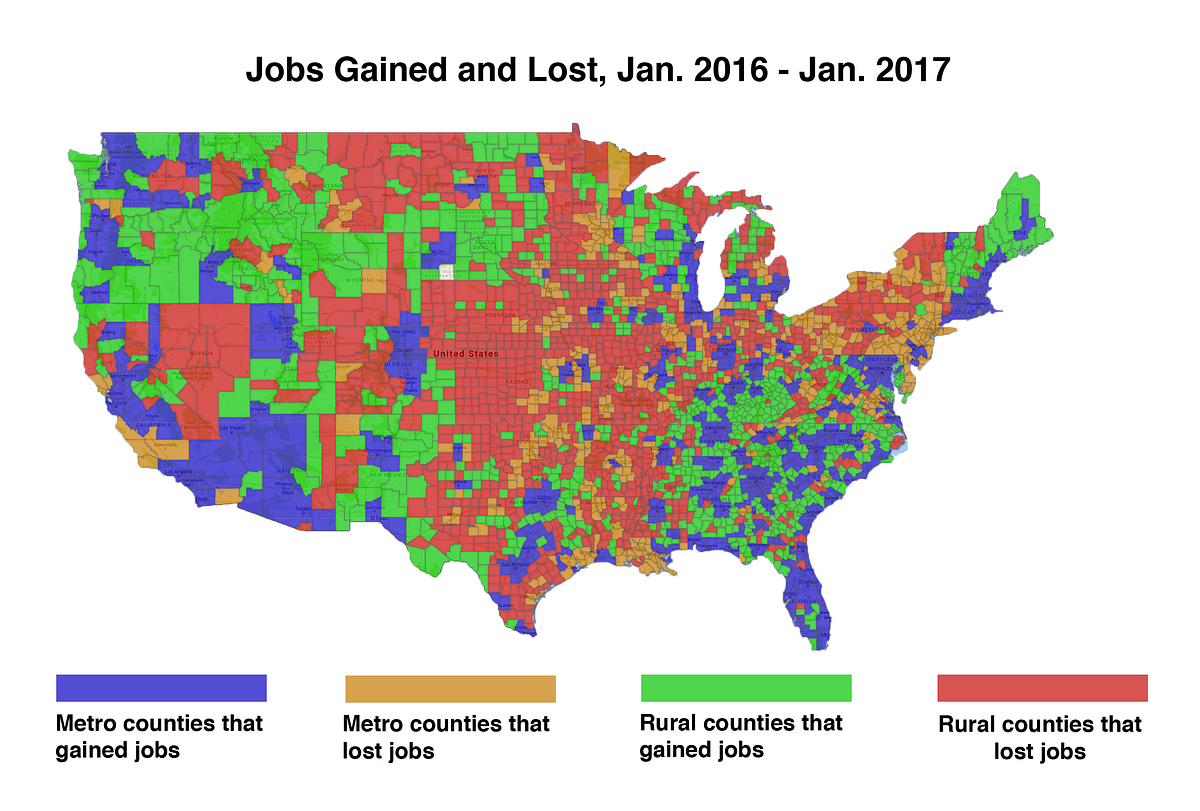

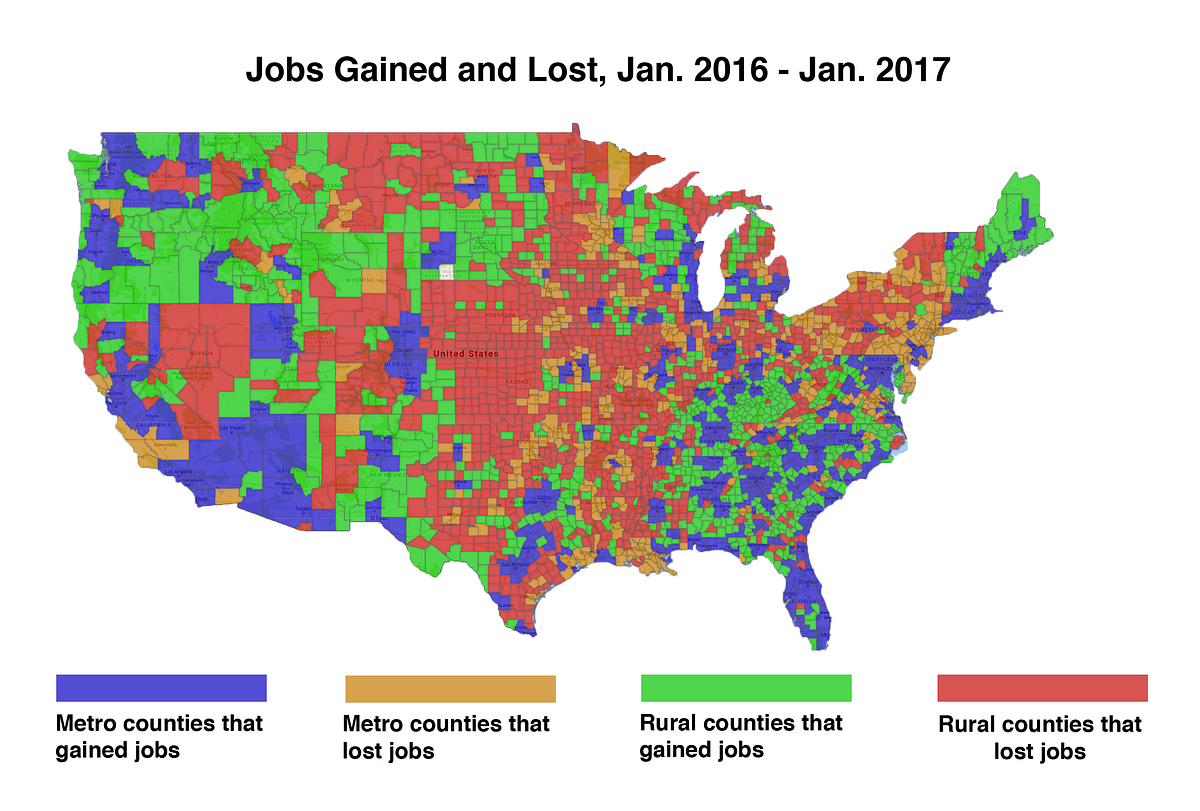

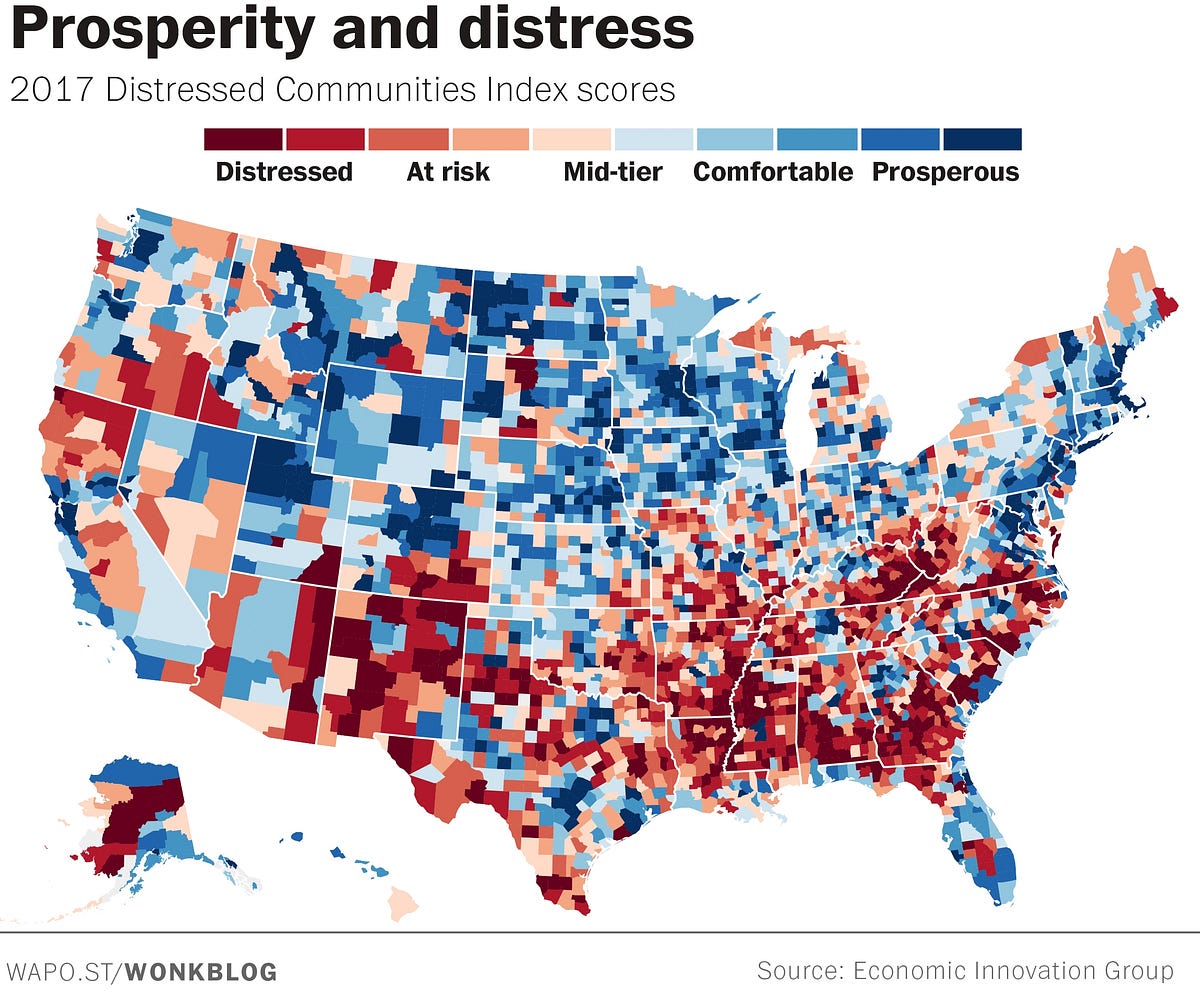

The Automation of an Increasingly Divided Country Source: Daily Yonder

Source: Daily Yonder

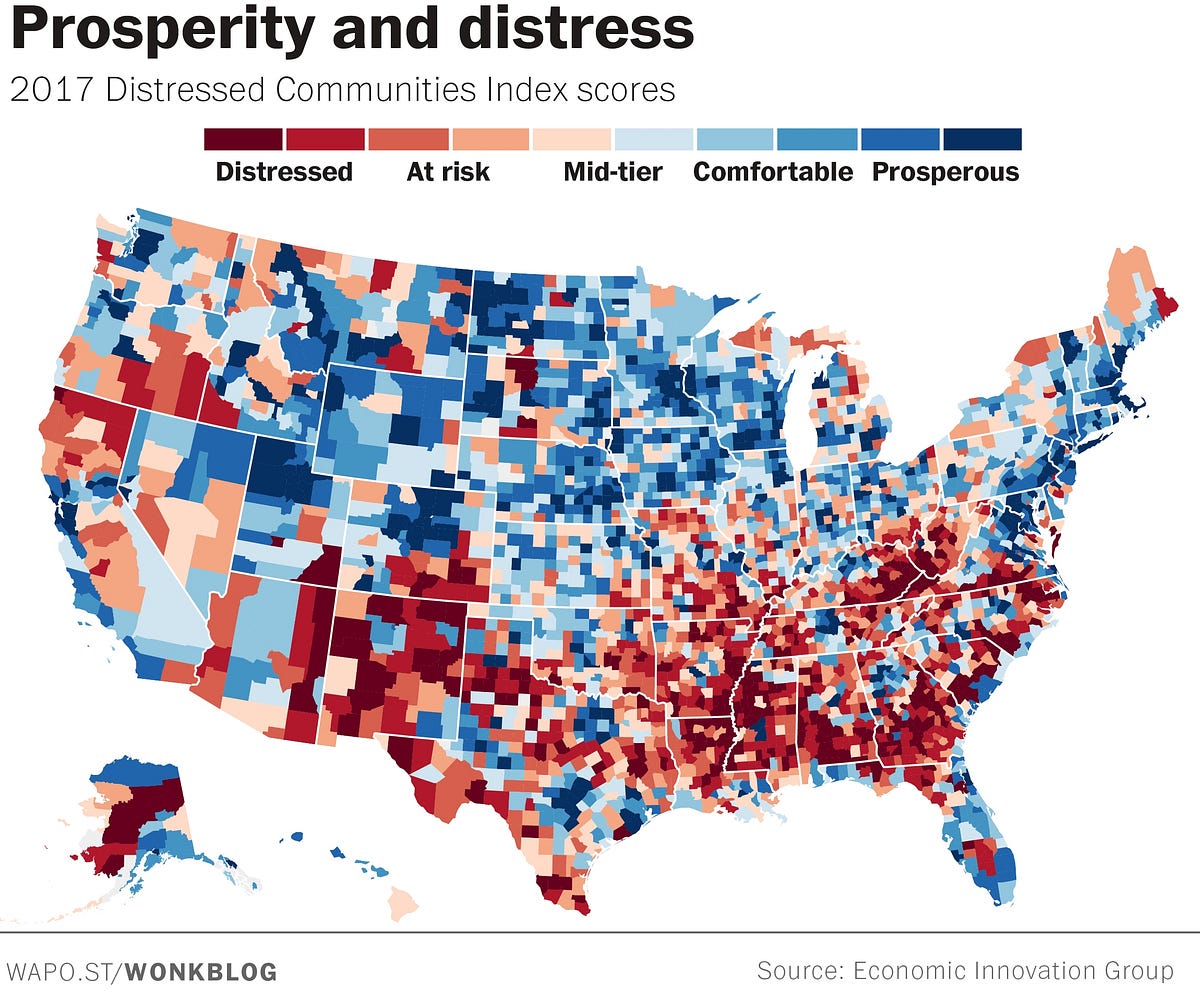

More than 52 million Americans are now

currently living in counties considered as being in economic distress.

A report by the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a bipartisan research and

advocacy organization, discovered a close link between community size and

prosperity, where counties with under 100,000 people are 11 times more

likely to be distressedthan counties with more than 100,000 people.

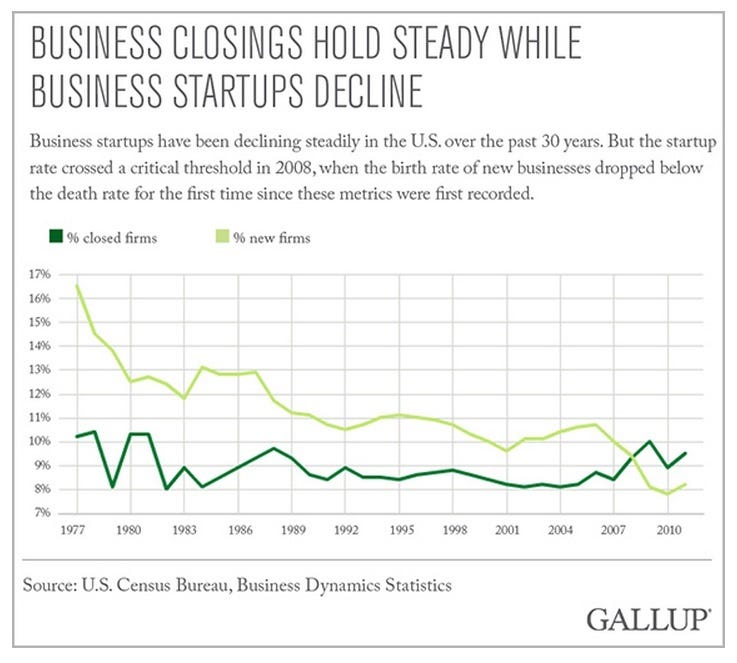

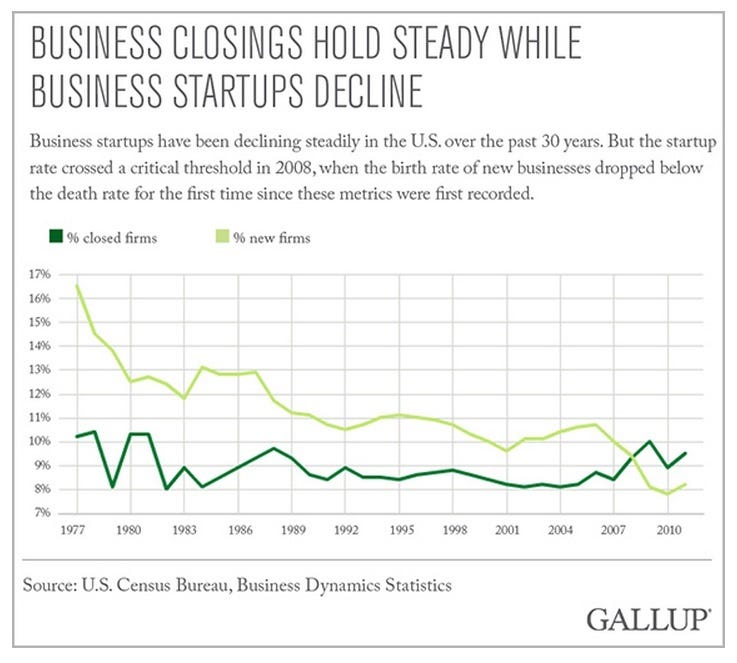

Source: Mauro Martino But the new

businesses being created are rising in value every year, which matches what

we’d expect to see from each new business using the latest technology to do far

more with far less.

But the new

businesses being created are rising in value every year, which matches what

we’d expect to see from each new business using the latest technology to do far

more with far less. Every year

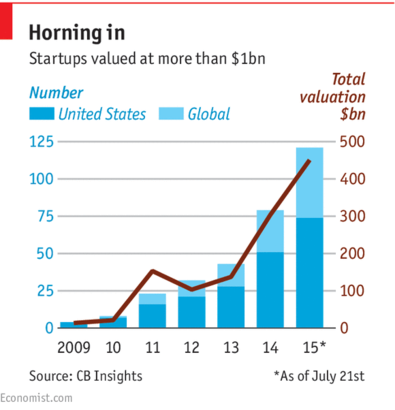

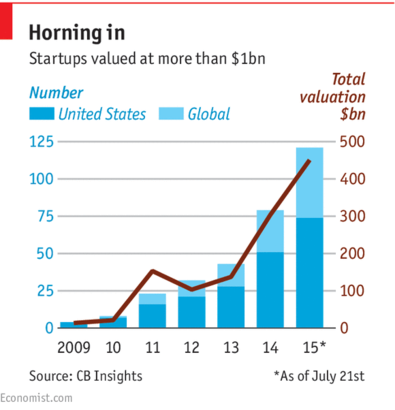

there are more new businesses worth over $1 billion. Look at Tesla versus early

20th century Ford Motors, or Instagram versus Kodak, or Facebook versus all the

newspapers that used to exist. These companies are worth hundreds of billions

of dollars and employ a fraction of the people as the most valued companies of

the past once did.

Every year

there are more new businesses worth over $1 billion. Look at Tesla versus early

20th century Ford Motors, or Instagram versus Kodak, or Facebook versus all the

newspapers that used to exist. These companies are worth hundreds of billions

of dollars and employ a fraction of the people as the most valued companies of

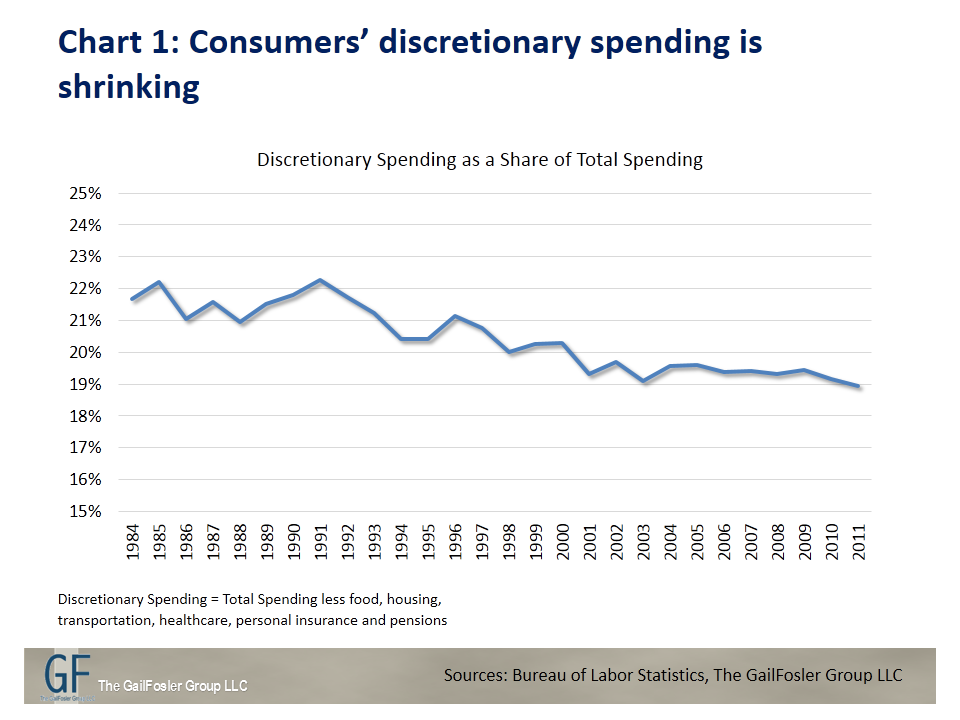

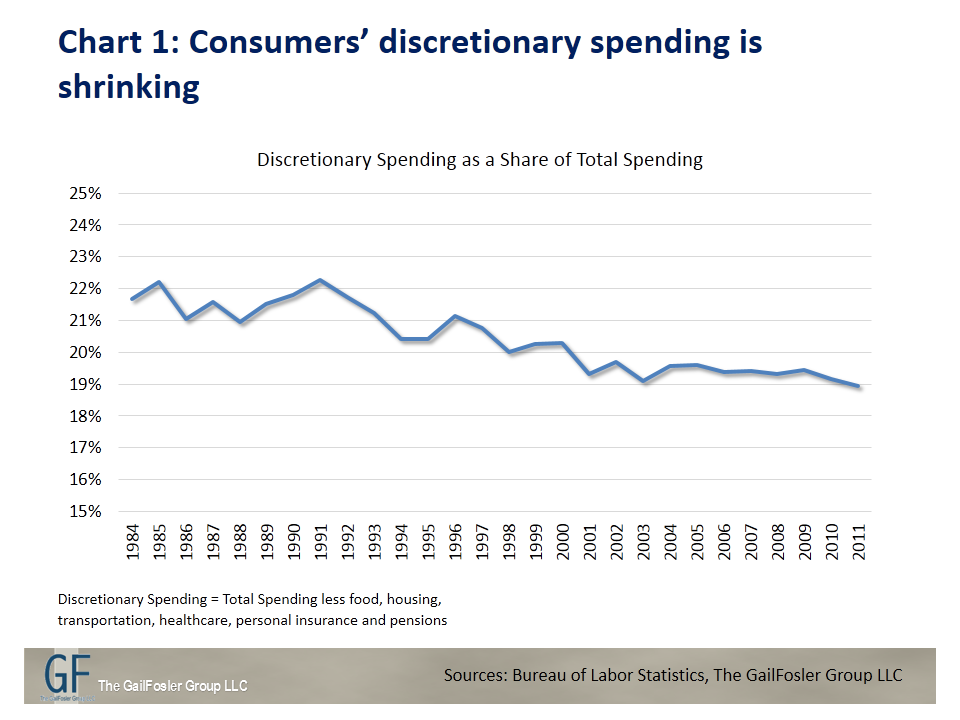

the past once did. There’s also

an assumption that human demand is infinite, and so no matter how many jobs are

eliminated by technology, a human demand for infinitely more stuff will always

create new jobs. This belief exists alongside continually shrinking

discretionary spending as a share of total spending. This should also not

surprise anyone. People can’t spend money if they don’t have any.

There’s also

an assumption that human demand is infinite, and so no matter how many jobs are

eliminated by technology, a human demand for infinitely more stuff will always

create new jobs. This belief exists alongside continually shrinking

discretionary spending as a share of total spending. This should also not

surprise anyone. People can’t spend money if they don’t have any.

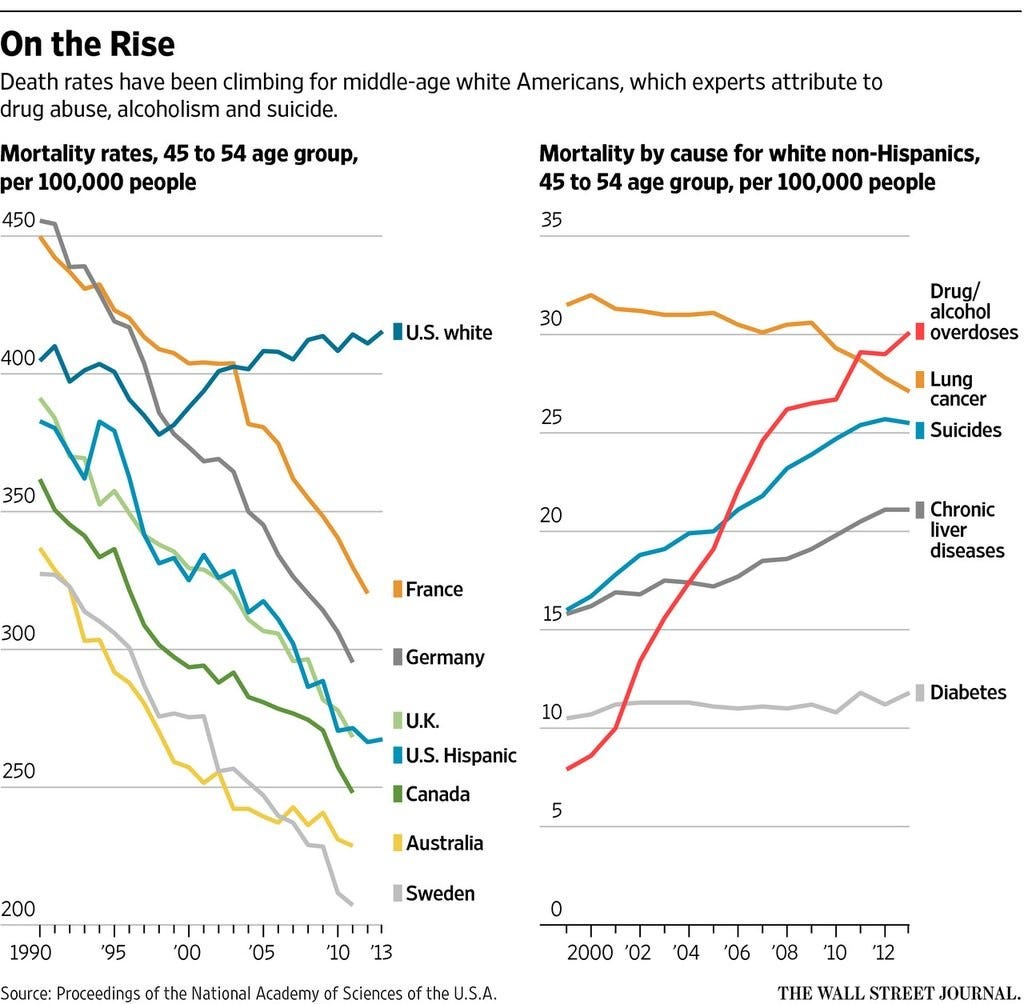

My fear is

that ignoring the problem will continue. Why not? We’ve ignored manufacturing

being automated. Yes, we know it happened, but we’ve pretended that everyone

just went on to find new paid work, without critically evaluating the nature of

that paid work. Unemployment isn’t a problem, right, because the unemployment

rate is at a record low? Tell that to the person who went from a 40-hour per

week career with benefits and a sense of security to three different jobs/gigs

without any benefits, working 80 hours per week to earn less total income in a

far more insecure life just trying to get by each month. Tell that to the

person who feels marriage has become something only the

rich can afford any more. Tell that to the person who attempted suicide, or

self-medicated their depression with opioids after their town’s

manufacturing plant closed down, obliterating their town’s local economy and

leaving them with no means of paying others for their own existence.

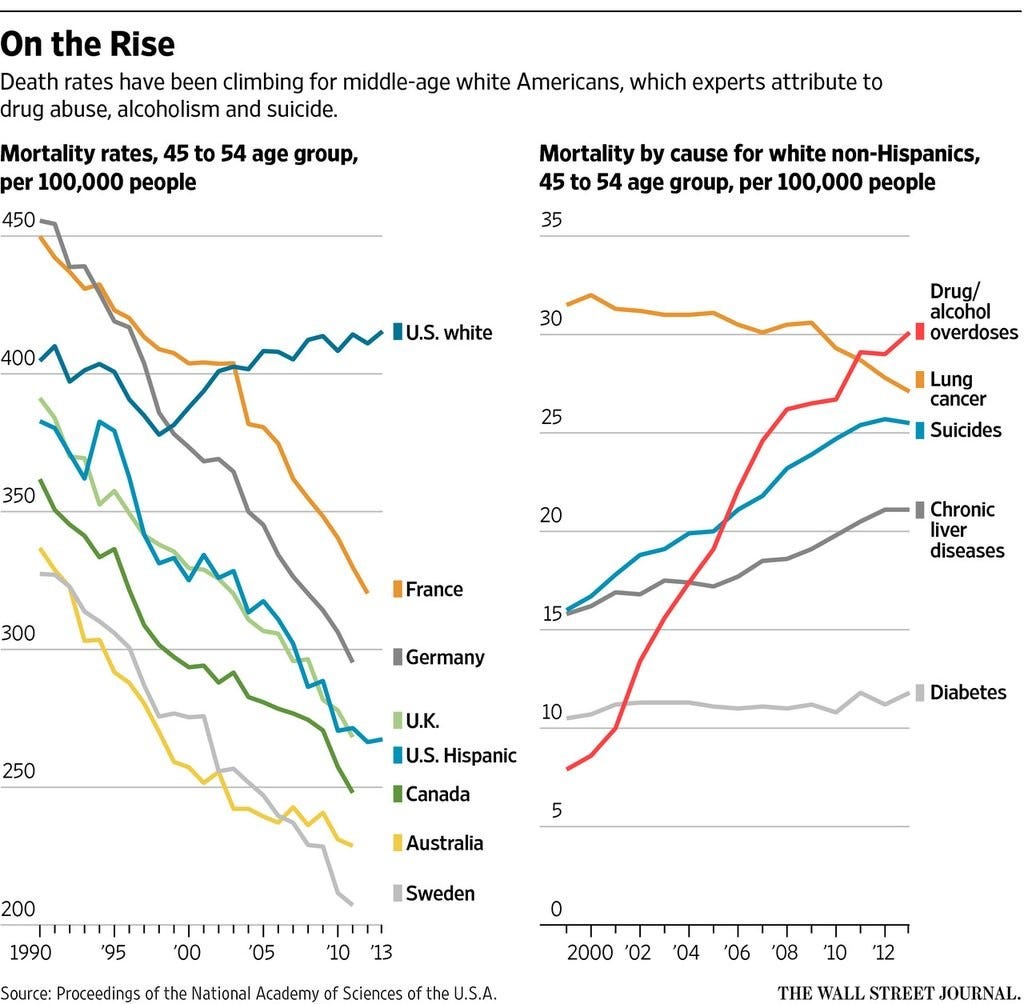

Source: New York Times

Source: New York Times