Most watch in disbelief as hordes of Middle Eastern migrants enter Europe with little to no resistance from border control. Whereas refugees are normally women and children, these migrants are for the most part young males of fighting age leaving a war zone. That prompts concerns on their true motives.

Europe is divided regarding its course of action against this flood of migrant resulting in inaction; meanwhile the flow intensifies: at the beginning of October 2015 the flow has increased to over 10,000 new migrants daily in Germany. Today we will explain how an armed conflict over a gas pipeline triggered this mass migration and considering the geopolitical consequences, forecast where oil prices will go from here.

The Heir to the Throne

In 1994, an unassuming eye doctor in London got a call to tell him that his brother had died unexpectedly in a car crash and that he had to move back in with his parents. Why? His father was Hafez al-Assad, the internationally reviled dictator of Syria, and our humble eye doctor was now commanded to prepare for his new inheritance - the Presidency of Syria.

Bashar al-Assad became president upon his father's death in 2000. He married the charming British-born Asma Akhras in December. Hafez al-Assad's foreign policy had been against the Western powers, which he resented for the colonial occupation of his country, and pro-Soviet Russia, which had sent military assistance and arms to Syria. The Western-leaning young couple worked to thaw relations with the developed world.

The Assads were invited to the capitals of Europe and forged friendly contacts with world leaders. By 2010, with the ruins of Saddam Hussein's regime smoldering in Iraq and a peace deal signed in Palestine, suddenly the path was clear from oil and gas producers in the Middle East, all the way to Europe. There remained just one last country to bring onside in order to get oil and gas piped through to a high demand region. That country was Syria.

Once Upon a Pipeline

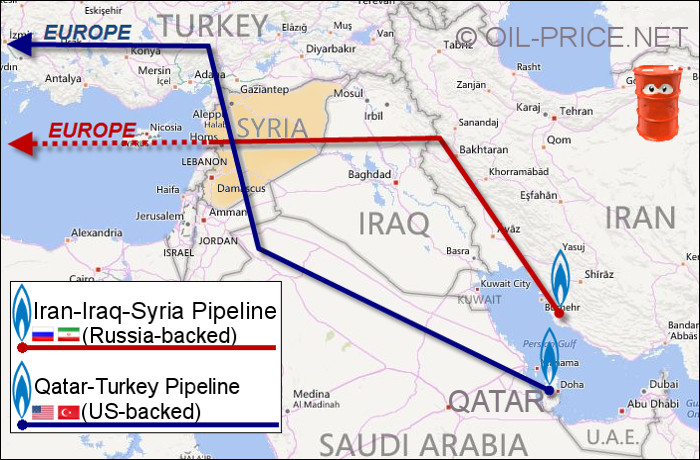

As oil-price.net reported back in 2012, Qatar needed to get its Qatar-Turkey" pipeline through Syria, and Europe looked forward to linking up with the world's largest gas producer because it was over-dependent on Russian supplies. Russia's unstable president Vladimir Putin had previously cut off gas supplies to Europe in the dead of winter 2009 after a dispute with Ukraine over gas royalties. The Russian military has since invaded Ukraine and given Putin's aggressive stance, Europe now urgently needs to find an alternate gas supply not controlled by Russia. This makes a middle-eastern pipeline coming through Syria a very attractive proposition.

The Assads soon realized that they were in a position of power. They decided to up the ante by creating an alternative source of fuel for a trans-Syrian pipeline. Most of the countries in the Middle East, including Syria are majority Sunni Muslim. The post-Hussein regime in Iraq was dominated by Shia Muslims, The Assads are Alawite Muslims - a Shia creed that the Sunnis from Qatar and Saudi Arabia would like to see wiped off the earth. So instead of the Qatar-Turkey pipeline, Assad stitched together a deal with the Shia administration in Iraq, together with Iraq's other neighbor, Iran - the largest Shia nation in the world. The Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline project was born.

Syria's economy was underdeveloped and the Assads needed oil money to keep their people placated. Their alternative pipeline plan would carry Iran and Iraq's gas to Europe, instead of gas from Qatar, and that option pleased Russia's Putin, because he already had long standing agreements in place with Iran, who were more amenable to gas price coordination with Russia. Moreover, as a long-term supporter of Syria, Russia had built up influence within the administration and the armed forces. Also Russia's only military base in the Mediterranean is located on the coast of Syria which would strategically allow Putin to control a second gas pipeline to Europe. Naturally this Iranian pipeline to Syria quickly became a top priority for Moscow. Assad and the Russians worked their contacts to dissuade the Qatar deal and promote the Iranian plan. Bashar and Asma thought they had forced Europe and the Gulf States to up their offer. Instead, they had made some very dangerous enemies.

Saudis need Assad overthrown

Saudi diplomatic efforts and generous contracts to US and UK arms manufacturers gave the Kingdom an unwritten call on the military of Western powers to fight its war for it. And so the Saudi king merely needed to lift a finger for President Obama and Britain's Prime Minister Cameron to schedule air strikes against Syria in an effort to overthrow Assad. At the end of August 2013, however, the British parliament voted against the action. That put pressure on the US president who calculated that Congress would follow suit and block any attack on Syria as well. Russia raised the stakes by moving warships into the Mediterranean, ready to defend Syria. Saudi Arabia's friends backed down, and the Saudi king resolved to solve the problem of Syria himself.

As Iran is liberated from US-imposed embargo, two power blocks have emerged in the Middle East - Iran, Iraq and Syria, which are all Shia-led, and the rest of the Arab world, which is Sunni and stands against the Shia. While America holds the alliance of the Sunni world, Russia is siding with the Shia-controlled nations.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar's first move was to fund the Muslim Brotherhood, which intended to impose Sunni control on all Middle Eastern countries. The Saudis persuaded the United States to endorse this policy and western media put a marketing spin on the rebellions of these Muslim fundamentalists, by dubbing their power grab "the Arab Spring". Once the Brotherhood's intolerance started to emerge in power, the US backed out and the Saudis tried a different tack.

The Saudis had another trick up their sleeve. Not only did the US refuse to overthrow Assad, but they then opened negotiations to loosen the oil embargo on Iran. The prospects of Iran coming back to the international oil market would heighten the growing over-supply of crude oil. Usually in these situations, OPEC was expected to cut its production to reduce oversupply in the oil market and make oil production profitable for all the other countries in the world. Saudi production quotas so exceed those of all the other OPEC nations that no production cut would be meaningful if the Saudis refused to cooperate.

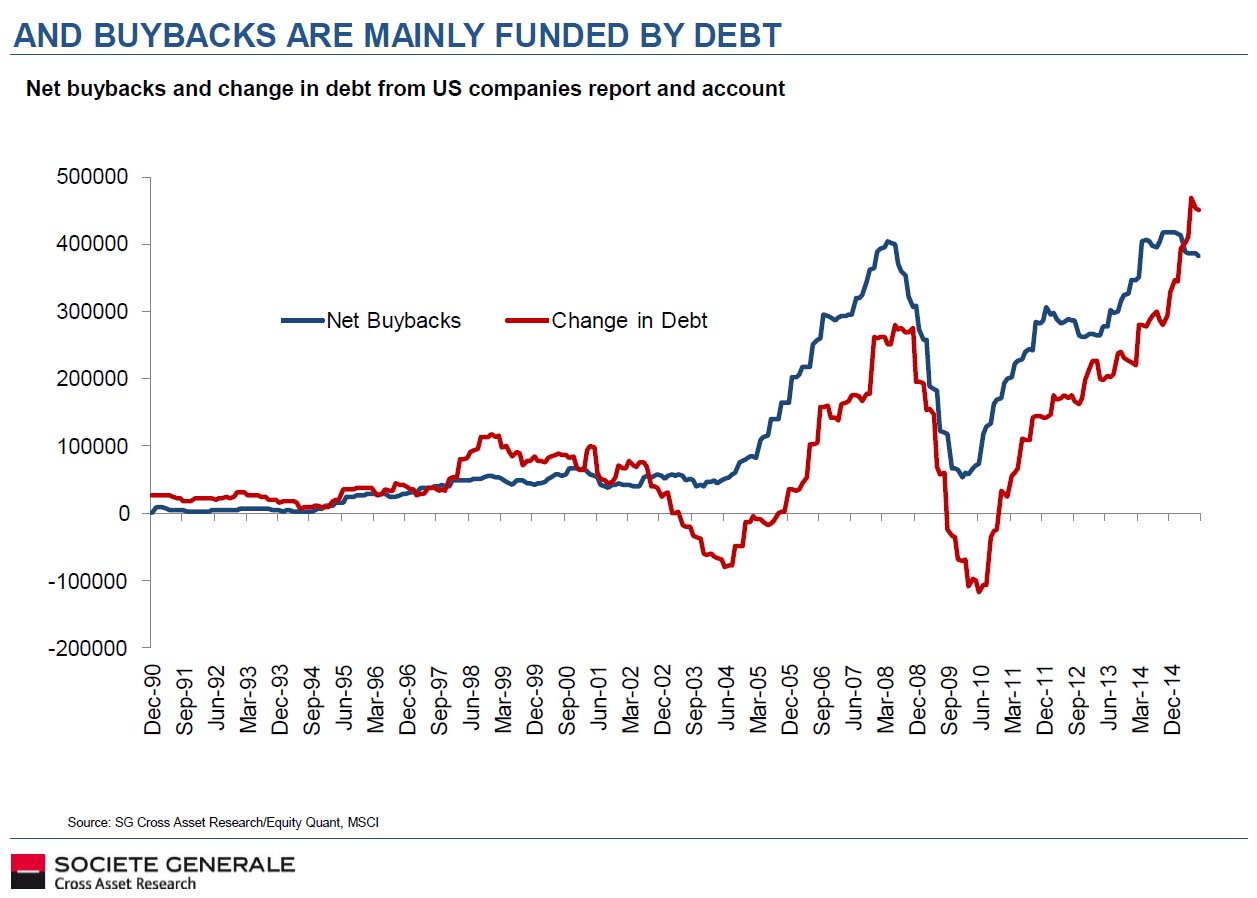

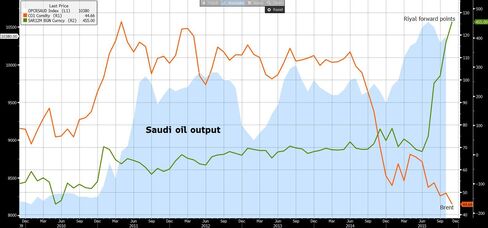

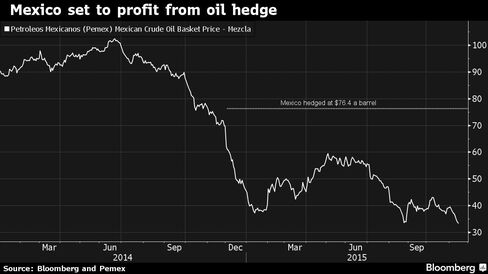

The Saudis came up with a new strategy that would punish Russia for their intervention in Syria, stall Iran from retooling its oil industry and cripple America's fracking production. They increased oil production and aggressively offered low oil prices to grab market share. The oil price fall conveniently stymied all the parties involved in keeping Assad in power.

Proxy War in Syria

Qatar and Saudi Arabia have been heavily involved with fostering and funding Sunni Muslim insurgent groups in Iraq and Syria, including the much-publicized ISIS. Disaffected and experienced Sunni administrators and soldiers in Iraq poured into ISIS, who offered them wages and self-respect.

ISIS are funded by Saudi Arabia and Qatar donors, but not controlled by them. Their leaders found it easy to quickly grab the Sunni dominated areas of Iraq and Syria, aided by the downtrodden locals. However, they have shown an ambivalent attitude in their administration. The leaders of national branches of ISIS seek income opportunities to enable them to advance ahead of rival branch leaders and gain policy independence from Saudi Arabia. In northern Iraq, they run the oil refineries they take over to make a profit. In Libya, they destroy them as offenses to God. The Libyan branch of ISIS prefers the easy money of people smuggling. Established smuggling routes also serve the long-term strategic ambition to project fighters worldwide.

ISIS-lead upheavals in Syria create a crisis that refugees are fleeing from, the ISIS-lead smuggling operations in Libya offer those refugees a route into Europe.

Labor Shortages

It is no coincidence that Germany suddenly decided to offer very generous welfare rewards to any illegal immigrant who can make it over the Mediterranean from the Libyan coast to Italian islands. Germany needs guest worker labor from poorer countries in order to keep its manufacturers competitive.

Germany's ability to continue exporting in the face of a high wage economy is hailed by their government as a tribute to the German education system. In truth, behind the scenes, the German government knows very well that their low wage, high output economy is a tribute to the Turkish education system. Despite objections from the general public, the German government has allowed unrestricted migration from Turkey since the 1980s. The low wage ambitions of migrant Turkish factory workers undercut the negotiating powers of German trade unions. German workers had to keep their wage demands low to keep their jobs from being handed over to Turkish unskilled labor.

But the economic emergence of Turkey in recent years caused the flow of cheap labor to Germany to dry up. Now the German government finds itself scrambling for more migrant labor to stave off inflationary pressures.

Divided Europe

The new German policy of serving its own interests, in hindsight can be seen as a long-term movement from the country's hope for European harmony, to its hegemony of the continent. The Schengen Agreement removed all border controls between EU member states. This was a step towards Germany's original goal of merging itself into a wider country. However, the downside of borderless Europe is that any illegal migrant who can make it into Italy, Greece or Spain then has the whole of the EU to roam across unhindered. Germany turned that weakness to its advantage in its endeavor to source cheap labor. Their siren call to the downtrodden of the Muslim world has seen the countries of southern and eastern Europe overrun by ambitious economic migrants. Germany received twice as many asylum applications in 2014 than Turkey did.

Towards the end of August 2015, Germany made matters worse by declaring that they would accept all refugees arriving from Syria. Unsurprisingly, the number of asylum seekers crowding into dinghies on the Libyan coast surged. The number that claimed to be Syrian went through the roof. By September, German officials estimated that 20 per cent of migrants arriving in that country are from Syria. The large majority is from other countries such as Sudan, Somalia and Afghanistan.

The German call for cheap labor worked well - too well. In 2014, 173,000 migrants applied for asylum. German officials estimate that this year, that number will be between 800,000 and 1 million. Their success has convinced many to follow suit - an estimated 20 to 30 millions are now considering migrating from the middle east to benefit from Europe's welfare system.

Although the German government wants a lot of migrants, its neighbors plagued with double-digit unemployment don't and European countries started re-imposing border controls. The Europhile dream of a borderless continent was trampled underfoot by Germany's grab for cheap labor.

In fact there is already ample statistical evidence that this "welfare migration" has significantly hurt European economies. In the Netherlands, 70% of Somalis live on welfare versus just 3 per cent for the native Dutch and 2 per cent for Polish migrants. According to Norway's Central Bureau of statistics, each non-European immigrant costs $660,000 over his lifetime.

Britain's experience echoes the continental figures. Over the last 17 years Britain has spent $180 billion on immigrants from outside the EU, namely on welfare, while foreign workers from within the EU contributed $6.6 billion to the British economy.

There is also an increased risk of terrorism - ISIS fighters are among migrants. According to Mike MCCaul, chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, "From a national security standpoint, I take ISIS at its word when they said, in their own words, 'We'll use and exploit the refugee crisis to infiltrate the West.' That concerns me." According to Lebanese officials, 2.2 per cent of Syrians crowding refugee camps are affiliated with ISIS. In other words, of the 10,000 migrants arriving in Germany daily, 220 are war-hardened ISIS fighters - though many others have comparable affiliations.

Germany's neighbors were not the only ones complaining about the policy of attracting unfiltered migrants - the German electorate rose up in protest in the face of this unprecedented geopolitical risk.

History repeats itself

A similar geopolitical situation unfolded in Lebanon 40 years ago. Back in the 60s and early 70s, Lebanon was a very westernized and dynamic center of regional trade. It was a former colony of France with a strong Christian presence dating back to the crusades. Beirut was often compared to Switzerland or Hong Kong and earned the nickname of "the Monaco of the Middle East".

At that time, nearby Jordan was housing 400,000 Palestinian refugees from the war with Israel. These refugees, embittered by their experience, turned fundamentalists. Their allegiance to the PLO was increasingly problematic so the King of Jordan evicted them. Homeless, and penniless Palestinians headed for prosperous Lebanon. Insisting on maintaining their traditional values, they created "a state within a state" under Sharia law against Lebanon's secular democratic model. Tensions increased as native Christians were soon outnumbered by Muslims and in 1975 a fully-fledged civil war broke out where countless were killed.

Today no-one would seriously compare Lebanon to Switzerland as they once did. We should remember three key facts, though. First, it took 400,000 refugees to destabilize of a westernized country of 2.6 million, or a ratio of roughly 1 to 7. Second, is that Lebanese leftists perceived the war as a "class struggle" (the poor against the rich) so they fought alongside Muslim fundamentalists against Christians during the Lebanese civil war. Finally, demands for welfare and the draining expense of expanding an army, frittered away Lebanon's wealth as all commerce stopped and the tax base disappeared

Domino Effect

The German government has found itself a clever formula. It has agreed to let in more than a million migrants this year, but it hasn't agreed to let them stay. This wordplay around the status of their visitors gives Angela Merkel a sufficient glow of piety to put her in pole position for the Nobel Peace Prize this year, but doesn't actually commit them to grant passports to anyone.

Germany has implemented a nine month selection window to keep the brightest migrants, who will plug their labor shortage. That's right, keep the best, reject the rest, but what will happen to those who cannot assimilate to a western society and are rejected? They can't be sent back to a war zone, and they can't remain in Germany. The borderless Schengen area provides the solution. In fact Germany is already laying plans for where to send its rejects. They forced through an EU ruling in late September which obliges other EU countries to take a percentage of refugees off their hands.

Some European leaders have been able to spot Germany's tactics and have already cried foul. The ensuing name calling and outright venom that flew between Berlin and Budapest, seat of the leader of the no-voting block's leader, Viktor Orban, shows cracks appearing in European unity.

Economic need may force the refugees to move on. Cut off from the much advertised generous state benefits in Germany, they will merely up sticks and mob over the borders to Austria, Poland, France and the Netherland in search of more handouts. As they link up with leftist radicals and religious extremists of those countries, a Lebanon style rebellion could develop.

While Germany, with 81 million people may be able control 1 million migrants (albeit not easily), it would spell doom for its smaller and vulnerable European neighbors, namely Denmark, Finland, Slovakia and Norway - each with 5 million inhabitants - much like it did in Lebanon 40 years ago.

There will be a "domino-effect" among European nations re-introducing pre-EU strong border controls, as Hungary has already done. This will significantly reduce trade between EU countries. Fewer trucks on the road mean less energy consumption, less commerce and lower tax revenues, higher deficits and a weakening Euro.

When the populations of Germany's neighboring countries get let in on Berlin's refugee filtering trick, the anger and mistrust between European nations that has been repressed for the last 25 years will resurface and may split the EU apart. Europe's competitive advantages will ebb away. We can expect that some strategic industries - those who can - flee Europe's geopolitical risk. Coincidently, Airbus SA recently announced its plan to relocate production of the upcoming A320 airplane to Mobile, Alabama USA instead of France. Going forward Europe's image will suffer irreparable loss while North America and Asia will remain stable and open for business.

Unintended Consequences

Oil-price.net has a long track record of successfully forecasting geopolitical risks tied to petroleum. In 2012 we predicted that armed militias would seize oil fields in Sudan, Libya and Nigeria and warned of the potential disaster that factions can cause in that region. The unintended consequences of the US invasion of Iraq switched the dominant religion in that country and created a Shia corridor from the heart of Afghanistan through to the Eastern Mediterranean coast; and made Saudi Arabia feel threatened.

The Saudi and Qatar plan to switch the Syrian government from Shia to Sunni promised the reward of a clear Sunni corridor from the gulf to the frontier of the European Union. However, their methods of achieving that goal drove Syria to plan a pipeline benefiting Iran and unleashed the chaos of extremist control of large areas of Iraq, Syria and Libya.

An unintended consequence of Europe's support for a Qatar-Syria gas pipeline free of Russian influence was the migrant crisis currently flooding Europe. The German government's idea to exploit the overwhelming tide of asylum seekers to gain cheap labor backfired into the de-unification of Europe.

The blowback caused by Saudi policy over the past few years extends beyond the Middle East, and it still hasn't played itself out.

The King of Oil and the Emperor of Gas

The Saudis intended to cripple Russia, Iran and US frackers through lower oil prices. However, all of those countries have joined the Saudis in increasing production since the price of oil started to fall in 2014.

If anyone is going to blink first, it won't be the USA, where some frackers have reduced their production costs from $70 per barrel to $20 per barrel.

Vladimir Putin based his entire political strategy on the exploitation of oil and gas, both as an income generator, and as a weapon against his perceived enemies. Russia's long term answer to the Saudi punch of lower oil prices had been in the making since Putin scared off the USA and the UK from bombing Syria. He didn't move his battleship to the Syrian coast as a gesture. He set himself up as the military overlord of Syria and took control of the one access point common to both the Iranian and Qatari pipelines.

The sudden revelation of the extent of Russia's involvement in Syria hit newsstands in early October 2015 when the Russian air force started bombing rebels in Syria. With international law on its side, Russia is defending the legitimate Syrian government against Saudi-backed terrorists.

Putin needs the income that his oil industry brings his government. The oil price drop and the Western sanctions against Russia hurt. His favorite industry, however, is gas. Russia controls 70 per cent of gas supplies to Europe and that brings him political advantages, as well as the ability to set falsely high gas prices. Europe's resolve to block trade with Russia will soon weaken during the freezing winter. With no hope of a pipeline bringing Middle Eastern gas through Syria, German-lead Europe will be easier to deal with. Russia is well placed to become Iran's new best friend. Putin is sitting pretty.

The Saudi Endgame

Saudi Arabia itself has a belligerent population and its government keeps the lid on dissent by being very generous with sweeteners for its people. Those subsidies are expensive and now that they are selling oil near cost price, the Saudi government is drawing down its saving.

The Saudis are running out of money and Western governments are starting to realize that they would rather Assad survived in office to help them fight the Saudi-funded ISIS. The comfortable relationship between the governments of Saudi Arabia and the USA seems to have broken down. A growing awareness among the populations of the West that Saudi Arabia funds terrorist organizations makes it harder for those democratic governments to make moves to support the Saudi King. So, Saudi Arabia is losing its big military ally, while Iran, Iraq and Syria become more closely involved with Russia.

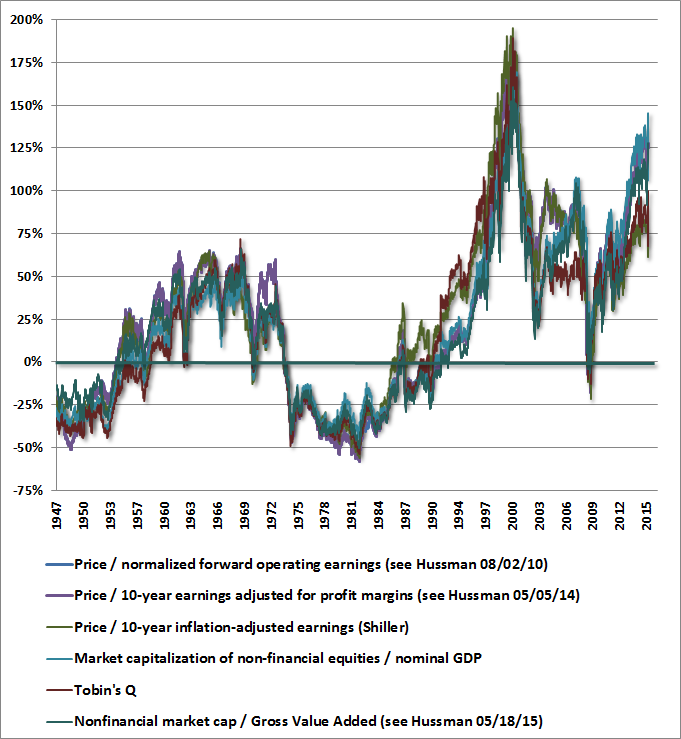

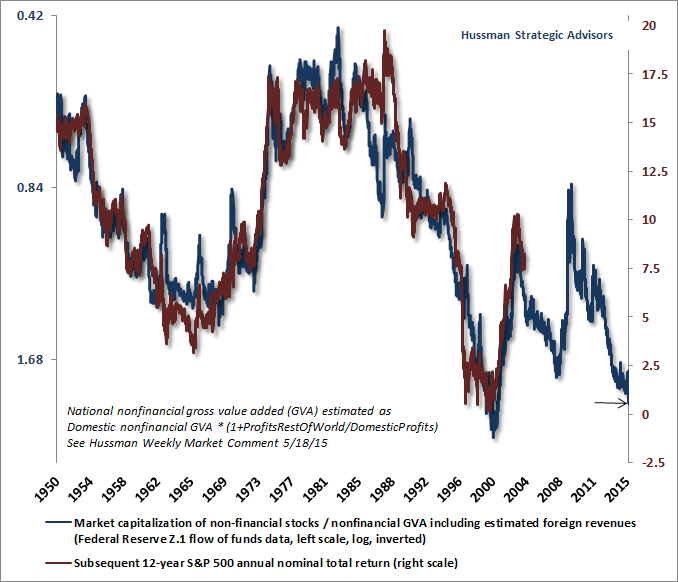

Low oil prices have become the new normal. The only way they will ever change is if a large amount of world oil output gets knocked out. It turns out this may be in the cards.

In booting ISIS out of Syria, Russian military planners most certainly will use a strategy called "funneling". Quite simply, with the assistance of allied Iran to the east, Russia will attack ISIS troops anywhere but south, forcing a retreat in that direction, thus "funneling" ISIS fighter south into rival Saudi Arabia. ISIS may find grassroot support within the kingdom and their natural target will first be -as always- oil fields. The resulting shortfall in oil and gas production will enable Russia and Iran to incease military spending and extend their strategical influence on the region, much like the US did.

An unintended consequence of the Saudi attempts to overthrow the government of Syria, may be the overthrow of the government of Saudi Arabia with its own medicine. Should ISIS be pushed into Saudi Arabia, expect oil prices to surge.