https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/nris-in-news/br-shetty-the-staggering-rise-and-incredible-fall-of-a-billionaire/articleshow/75381757.cms

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Wednesday, April 29, 2020

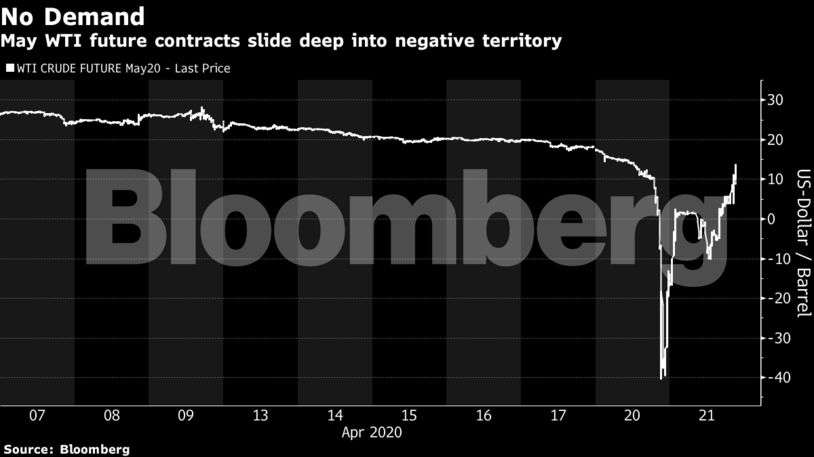

The 20 minutes that broke the US oil market.

It was evident from the very beginning on April 20 that the oil market was headed for trouble.

Frantic sell orders had been pouring in overnight and any traders who connected to the Nymex platform that morning could see a bloodbath was coming. By 7 a.m. in New York, the price on a key futures contract -- West Texas Intermediate for May delivery -- was already down 28% to $13.07 a barrel.

Thousands of miles away, in the Chinese metropolis of Shenzhen, a 26-year-old named A’Xiang watched events unfold on her phone in stunned disbelief. A few weeks earlier, she and and her boyfriend had sunk their entire nest egg of about $10,000 into a product that the state-run Bank of China dubbed Yuan You Bao, or Crude Oil Treasure.

As the night wore on, A’Xiang began preparing to lose it all. At 10 p.m. in Shenzhen -- 10 a.m. in New York -- she checked her phone one last time before heading to bed. The price was now $11. Half their savings had been wiped out.

As the couple slept, the rout deepened. The price set new low after new low in rapid-fire succession: the lowest since the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, the lowest since the oil crises of the 1970s, the first time ever below zero.

And then, in a 20-minute span that ranks among the most extraordinary in the history of financial markets, the price cratered to a level that few, if any, thought conceivable. Around the world, Saudi princes and Texan wildcatters and Russian oligarchs looked on with horror as the world’s most important commodity closed the trading day at a price of minus $37.63. That’s what you’d have to pay someone to take a barrel off your hands.

Many things about the explosive, flash-crash-like nature of the sell-off are still not fully understood, including how big a role the Crude Oil Treasure fund played as it sought to get out of the May contracts hours before they expired (and which other investors found themselves in the same position). What is clear, though, is that the day marked the culmination of the oil market’s most devastating crisis in a generation, the result of demand drying up as governments around the world locked down their economies in an attempt to manage the coronavirus pandemic.

For the petroleum industry, it was a grimly symbolic moment: The fossil fuel that helped to build the modern world, so prized it became known as “black gold,” was now not an asset but a liability.

“It was mind-bending,” said Keith Kelly, a managing director at the energy group of Compagnie Financiere Tradition SA, a leading broker. “Are you seeing what you think you’re seeing? Are your eyes playing tricks on you?”

US. ETF Pain

While the deeply negative prices of that Monday were largely limited to the U.S., and in particular the soon-to-expire WTI contract for May delivery, the world felt the shockwaves, with ripple effects dragging global prices to the lowest since the late 1990s.

Traders are still piecing together the confluence of factors that led to the collapse. And regulators are scrutinizing the issue, according to people familiar with the matter.

For small-time investors in Asia like A’Xiang who bet enthusiastically on oil, though, it has been a reckoning.

She awoke to a text at 6 a.m. from Bank of China informing her that not only had their savings been lost but that she and her boyfriend may actually owe money.

“When we saw the oil price start plunging, we were prepared that our money may be all gone,” she said. They hadn’t understood, she said, what they were getting into. “It didn’t occur to us that we had to pay attention to the overseas futures price and the whole concept of contract rolling.”

In all, there were some 3,700 retail investors in Bank of China’s Crude Oil Treasure fund. Collectively, they lost $85 million.

Soon, events would catch up with mom-and-pop American investors who had made much the same bet as A’Xiang -- that oil had to go back up -- by buying the United States Oil Fund, an exchange-traded fund known as USO.

That fund, into which investors poured $1.6 billion the previous week, hadn’t been holding the May WTI contract on last Monday. But the rout sparked a chain reaction in the market that burned these investors, too.

The day’s events were set in motion more than two weeks earlier, with the pandemic shattering economies and stalling demand for oil: flights were grounded; traffic jams disappeared; factories ground to a halt.

The below-zero price scenario was, in some corners of the market, starting to be considered. On April 8, a Wednesday, CME Group Inc, which owns the oil-futures exchange, advised clients that it was “ready to handle the situation of negative underlying prices in major energy contracts.”

That weekend, producing nations led by Saudi Arabia and Russia finalized their response to the crisis: a deal to slash production by 9.7 million barrels a day, amounting to a tenth of global production. That wouldn’t be nearly enough. Refineries started shutting down. Buyers for cargoes of oil for immediate delivery in physical markets disappeared.

Futures prices remained, for a while, relatively steady.

That was in part thanks to folks like A’Xiang. In China, investors large and small were betting on higher commodity prices, believing the world would overcome the virus and that demand would bounce back. Bank of China branches posted ads on Wechat, showing an image of golden barrels of oil under the title “Crude oil is cheaper than water”.

Yet on April 15, CME offered clients the ability to test their systems to prepare for negativity. That’s when the market really woke up to the idea that this could actually happen, said Clay Davis, a principal at Verano Energy Trading LP in Houston.

“That’s when the dam broke,” he said.

Physical Delivery

By the time Monday April 20 rolled around, most ETFs and other investment products -- though not the Crude Oil Treasure fund -- had shifted their position out of the May WTI contract into the next month.

Futures contracts are settled by physical delivery, and if you happen to get stuck with one when it expires, you become the owner of 1,000 barrels of crude. Rarely does it come to that.

But now it was.

The physical settlement for the benchmark WTI takes place at Cushing, Oklahoma. When storage tanks there fill up, the price on the expiring contract can plunge and become disconnected from the global market. With demand evaporating, inventories at Cushing were soaring. In March and April, they climbed 60% to just under 60 million barrels, out of a total working capacity of 76 million –- and analysts reckon much of the remaining space is already earmarked.

So on the crucial Monday, the penultimate day of trading in the May WTI contract, there were precious few traders able or willing to take physical delivery.

Much of the market was focused then on the settlement price, determined at 2:30 p.m. in New York. Investment products –- including Bank of China’s –- typically seek to achieve the settlement price. That often involves so called trading-at-settlement contracts, which allow oil traders to buy or sell contracts ahead of time for for whatever the settlement price happens to be.

No Buyers

On that afternoon, with trading volumes thin and sellers outnumbering buyers, the trading-at-settlement contracts quickly moved to the maximum discount allowed, of 10 cents per barrel. For a period of around an hour, from 1:12 p.m. until 2:17 p.m., trading in these contracts all but dried up. There were no buyers.

The result was the carnage of that afternoon. At 2:08 p.m., WTI turned negative. And then, minutes later, sank to as low as minus $40.32 before rebounding slightly at the close.

“The trading at settlement mechanism failed,” said David Greenberg, president of Sterling Commodities and a former member of the board at Nymex. “It shows the fragility of the WTI market, which is not as big as people think.”

Prices in the U.S. physical market, set by reference to the WTI settlement, also plunged, with some refiners and pipeline companies posting prices to their suppliers as low as minus $54 a barrel.

Bank of China’s investment product offers an explanation of why the move below zero was so dangerous. The bank had demanded investors like A’Xiang put up the entire cost of what they were buying in advance. That meant the bank’s position looked risk-free.

But not if prices dropped below zero: then there wouldn’t be enough money in the investors’ accounts to cover the losses.

The bank had a total position of about 1.4 million barrels of oil, or 1,400 contracts, according to a person familiar with the matter. It wound up having to pay about 400 million yuan ($56 million) to settle the contracts.

Across the investing world, others were faced with similar risks. ETFs could be bankrupted if the price of the contracts they held went below zero. Facing that possibility, they shifted a large chunk of holdings into later delivery months. Some brokers barred clients from opening new positions in the June contract.

The moves amounted to a new wave of selling that swept across oil markets. On Tuesday, the June WTI contract plunged by 68% to a low of just $6.50. And this time it was not limited to U.S. contracts: Brent futures also plunged, hitting a 20-year low of $15.98 on Wednesday, driving the price of Russian, Middle Eastern and West African oil that is priced relative to it to levels near zero.

CFTC’s Top Priority

Harold Hamm, chairman of Continental Resources Inc., called for an investigation, saying that the dramatic plunge in the last minutes of Monday “strongly raises the suspicion of market manipulation or a flawed new computer model.”

Within the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, unpacking what occurred during those final minutes of trading on April 20 has since become top priority, according to people familiar with the matter. While reviews and investigations into what occurred are just beginning, thus far, top officials believe the moves were likely the result of a confluence of economic and market factors, rather than the result of market manipulation.

An issue the CFTC is exploring is whether the storage capacity data posted by the U.S. Energy Information Administration accurately reflected the actual availability of space, two of the people said.

“The temporarily negative price at which the WTI Crude futures contract traded earlier this week appears to be rooted in fundamental supply and demand challenges alongside the particular features of that futures product,” CFTC Chairman Heath Tarbert told Bloomberg News.

Nonetheless, he added: “CFTC is conducting a deep dive to understand why the WTI price moved with the velocity and magnitude observed, and we will continue to oversee our markets’ role in facilitating convergence between spot and futures prices at expiration.”

The CME, for its part, argues that Monday’s plunge was a demonstration of the market working efficiently. “The markets worked exactly how they’re supposed to do,” CEO Terry Duffy told CNBC. “If Hamm or any other commercials believe that the price should be above zero, why would they have not stood in there and taken every single barrel of oil if it was worth something more? The true answer is it wasn’t at that given moment in time.”

Whoever is right, the events of the week have changed the oil market forever.

“We witnessed history,” “For the sake of oil-market stability,” this “should not be allowed to happen again.”

Tuesday, April 28, 2020

6 Visionaries Shaping The Future Of Transportation

This is the age of wild rides that are transforming the personal transportation sector into something worth more than ever. We not only have the soon-to-be available space tourism, but we’ve also got the even more futuristic colonization of Mars, which is about transportation as much as it is about anything.

On the slightly more sober side, we’re looking at the mass monetization of electric vehicles, and finally--a ride-sharing company that’s as green as Millennials want it to be. Behind it all are six men who have positioned themselves to transform the transportation sector, forever.

#1 Elon Musk

Musk is the man behind the electric vehicle revolution, but he’s much more than that. For a company that was once given an outside chance against deep-pocketed ICE heavyweights, Tesla (TSLA) is suddenly being hailed as a clean energy revolutionary and Wall Street cannot seem to get enough of the EV maker. Coronavirus aside, Wall Street is exceedingly bullish on Tesla right now.

Musk is likely to emerge with three crowns on the ground: EVs, solar, and clean energy. Each revolutionary.

It may seem easy to overlook Tesla’s solar business considering that the solar panel and battery segment brought in just six percent of the company’s revenue in 2019. But with the meteoric rise of ESG investing over the past couple of years, many companies, including traditional fossil fuel companies, have been investing in clean energy projects including solar and wind energy at an unprecedented rate. But Musk’s big picture transportation transformation bid is in outer space, through his private company, SpaceX.

In September, Musk unveiled the Starship spacecraft designed to carry 100 passengers and cargo to space. SpaceX announced test flights would start soon, with plans to land on the moon before 2022. And the private company just penned a deal with Space Adventures to fly private citizens to orbit aboard their Crew Dragon spacecraft next year.

Northern Sky Research predicts the suborbital and orbital tourism market could be worth as much as $14 billion in revenue worldwide by 2028.

#2 Sayan Navaratnam

While Branson, Bezos and Musk are busy with “fly-me-to-the-moon” sentiments, Sayan Navaratnam-- planning to join the other transportation gurus—is quietly making moves on a more Earthly scale.

With a focus on sustainability and progress, he’s brought us Facedrive, the next-gen ride-sharing company that gives the segment’s key customer base exactly what they want: A green alternative in the fossil-fuel driven ride-sharing sector.

Millennials are driving a new mega-trend: impact-investing. Facedrive (FD.V)--the first ride-sharing company that contribute to planting a tree while you ride, and choose exactly what kind of footprint you want to leave behind.

This is a new challenge to Uber, which simply hasn’t sunk its teeth into the mega-trend of ESG investing. Musk gets it, and so does Jeff Bezos--after all, the richest man on the planet just committed $10 billion to a Global Earth Fund. Sayan gets it, too. Green stocks will eventually eclipse the current technology monopolies, and even the world’s top oil traders are going green.

The biggest disruption in the world right now--outside of the coronavirus--is that major hedge funds are giving in to the pressure and moving money into things that are environmentally and socially responsible. Just ask Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock--one of the world’s largest hedge funds. He says climate change has become a “defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects”. Facedrive caught on to the mega-trend years ago.

“We’re all about grabbing onto the biggest trends in tech before they’re mega-trends. So that takes us back to 2016, when we first came up with the idea. Whenever a major new trend emerges, it’s the job of the truly innovative to step back and say ‘OK, this is an explosively great idea - so what’s wrong with it?’ When you figure that out, and you’ve got the right network and the right people behind you, you can jump in on one of the biggest trends and disrupt a massive market at exactly the right time,” Navaratnam said.

It’s all about choice these days, and the disruption here is Facedrive’s offer of choice to the customer, who can seamlessly choose whether they want an EV or a hybrid, rather than a conventional car. And even if they choose conventional, they’re still making a green choice because the CO2 is being offset for them.

Already, Sayan is attracting huge names with Facedrive because it’s been recognized as the #1 eco-friendly and socially responsible TaaS (Transportation as a Service) platform. In addition to celebrities, including Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith, WestBrook Global Inc. is also on board. The company has even partnered with a major telecom firm to offer drivers significant discounts.

A recent study by the Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that the average (U.S.) ride-hailing trip results in 69% more pollution than whatever transportation option it displaced. 3,500 trees later, Facedrive hasn’t only latched on to the mega-trend, it has helped drive it--literally.

The news flow has been as fast as the rate of infection in the United States. In the span of only several weeks, Facedrive has announced global expansion to Europe and the United States, acquired an innovative carpooling platform called HiRide that is storming the Canadian long-distance ride-share segment

#3 Richard Branson

In February, Branson’s Virgin Galactic (SPCE) launched its new “One Small Step” qualification process, which means that for $1,000, the most serious about flying to space can buy their way to the front of the line for reservations on a space flight whose timing and price remains elusive still, even though tickets for the inaugural flights have earlier been priced at $250,000 apiece.

So far, 7,957 people have signed up, including Justin Beiber and Leonardo DiCaprio.

But this is a futuristic endeavor, so profits are also futuristic.

Virgin Galactic posted its first public earnings in the last week of February, showing a net loss of $72.8 million in Q4 2019. That won’t really put much of a crimp in Branson’s net worth of $5.2 billion, and he is just fine knowing that in the not-so-distant-future, he’ll be taking people on excursions to space. It’s worth the wait for the profit.

After all, the global space industry is expected to generate revenue of $1.1 trillion or more in 2040, up from the current $350 billion, according to a recent Morgan Stanley estimate.

Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo went through its first supersonic, rocket-powered flight test in California in April, and is expected to begin commercial operations at Spaceport America in New Mexico as early as next year.

Branson is also the first in this cosmic segment to go public. Last October, Virgin Galactic Holdings became the first space tourism company to hit public markets after listing on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).

Each space venture wildly different from the next: Branson’s relies on a space plan dropped from a carrier aircraft, and only then does the rocket kick in, boosting passengers high into the atmosphere. For this reason, Virgin Galactic is bound to get there sooner, because it’s not going as far.

#4 Jeff Bezos

But Branson has competition, not least from the world’s richest man, Amazon’s (AMZN) Jeff Bezos.

Bezos's Blue Origin is a private space company that hopes to send paying customers beyond Earth in the very near future. It also seeks to plot the pathway for millions of people to live and work in space.

Bezos will use Blue Origin’s New Shepard space system to launch customers to the edge of space in a capsule that separates from a small rocket and then comes back to Earth under parachutes. Last May, Bezos revealed Blue Origin's new Blue Moon lander, which will bring payloads to the moon.

When Bezos sold $1.84 billion in Amazon stock in early February, the immediate speculation was that he was going to spend it on his space venture, Blue Origin, to catch up with Elon Musk and his private company, SpaceX, which tends to hog the headlines.

Indeed, just a month ago, Blue Origin opened a new rocket production facility in Huntsville, Alabama, where BE-3U and BE-4 engines will be made. But before we get stellar, we’re going to get green.

Space will have to wait a little while, but in the meantime, there are three contenders in the cosmos, and two major contenders on the ground. All four of them are the present and future of a massively lucrative and evolving transportation industry.

#5 Sundar Pichai

Sundar Pichai is the mastermind CEO of Alphabet (GOOGL), Google’s parent company. Under Pichai, Alphabet has embarked on some of its most exciting and innovative projects, including the acquisition and investment in Waymo, a leading company in the autonomous vehicle revolution.

Despite its late arrival to the automotive game, the company has made major waves in developing and deploying fully autonomous vehicles. In fact, as of January, Waymo’s self-driving cars have traversed a total of. 20 million miles on public roads – a major feat to say the least. Waymo’s latest figures make it the de-facto leader in the self-driving car space, surpassing China’s Baidu and Russia’s Yandex.

“To put this in perspective, 20 million miles of driving experience is the equivalent of driving 800 times around the globe, making 40 trips to the moon and back, and accumulating 1,400 years of driving experience for an average American driver,” wrote the company in a press release. “As we drive the next 10 million miles and beyond, we’ll continue to scale our fully driverless miles, grow our community of riders, and tackle new geographies and related complexities, empowered by our fifth-generation hardware suite.”

#6 Søren Skou

As the relatively new CEO of A.P. Moller-Maersk (AMKBY), Søren Skou has made significant progress towards pushing the company into the future. From its green initiatives to its technological edge, Maersk has grown significantly under Skou.

Maersk’s ambitious environmental plans include the development of a full fleet of zero-carbon ships by 2030, and it’s already well on its way. Additionally, the company plans to be completely carbon free by 2050.

While it’s environmental focus has been key to its investor appeal, its technological edge has positioned it as a leader in the industry. In 2018, the company deployed the first of many fully automated and fully electric container ships. And in 2019, it even deployed a team of autonomous robots at the Los Angeles docks, a move which has been well received by both dock workers and investors alike.

Monday, April 27, 2020

Oil markets have a timing problem

For more than a century, oil has been among the world’s most vital commodities. On April 20th it became less than worthless. The price of the May futures contract for West Texas Intermediate (wti) crude plunged to the hitherto unfathomable level of -$40. The price of Brent crude, the international benchmark, sank too, before both seemed to recover, with the front-month contracts settling at $13.78 for wti and $20.37 for Brent on April 22nd. But oil markets still have a timing problem.

As governments try to contain the spread of covid-19, demand for oil has fallen faster and farther than at any point in history. Production has been slower to ebb, so storage tanks are filling up. The Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (opec) and its allies this month announced a historic deal to cut production. On April 20th America’s president, Donald Trump, said his government might buy as much as 75m barrels of crude for America’s strategic reserve. But output is unlikely to drop quickly enough to bring oil markets into balance in May, June or even later this summer. As crude inventories rise, so does the pressure on the market.

The May contract for wti, though idiosyncratic in some ways, exemplifies the disaster scenario. The contract’s last day of trading was April 21st. The price plunged on April 20th, as traders realised they owned crude to be delivered to Cushing, Oklahoma, in May, but that Cushing would probably have no available tanks to store it.

The pressure on the global market is less extreme, but not entirely dissimilar. On April 12th opec and its allies promised to restrain output by 9.7m barrels a day in May and June, their biggest ever cut. The accord was too late, though, to deal with the implosion of demand in April. The International Energy Agency expects oil demand to sink by 29m barrels a day this month, compared with April 2019, equivalent to a third of global supply.

The agreement may be insufficient to deal with continued declines in demand in May, too, not least because the actual cuts are less impressive than the headline suggests. Not all of the more than 20 parties to the deal may comply. Moreover, Saudi Arabia, Russia and others in the group agreed to cut output not from the levels of February, but from an even higher base. The collective cut, compared with February of this year, is therefore closer to 7.5m barrels a day, reckons Bernstein, a research firm.

It is unclear if or when deeper cuts will come. Mr Trump helped broker the opec deal—America is now the world’s biggest crude producer—and is weighing further measures to support prices. But any purchase for America’s strategic reserves would require the approval of Congress. Regulators in Texas are mulling a cap on that state’s production, but a meeting on April 21st ended without agreement.

Market-driven declines in production are more likely, particularly after the nightmare of the May wti contract. But so far companies’ declared cuts have been too tepid: they are often loth to stop production, as restarting a well can be costly. Bernstein therefore expects global supply to exceed demand in the second quarter by more than 13m barrels a day.

In the meantime, storage across America is filling up rapidly, and could reach tank tops in June. On April 22nd the country’s Energy Information Administration reported that crude inventories had reached 519m barrels, close to the record of 535m set in 2017. Brent crude is seaborne and therefore less vulnerable to transport and storage problems than landlocked wti. But it too faces constraints. The volume of oil stored on ships has jumped by 70% since the beginning of March, according to Kpler, a market-data firm. And even more oil is borne on ships still steaming towards onshore crude tanks, which Reid I’Anson of Kpler estimates are already about 85% full.

Unprecedented circumstances are bringing unprecedented behaviour. Oil is usually stored in giant ships such as a Suezmax, or the aptly named Very Large Crude Carrier, or onshore near big ports or population centres, such as Rotterdam or New York. Ben Luckock of Trafigura, a big trader, says firms such as his are now considering rail cars, small barges or even parked trucks. The price of a contract for a major crude benchmark may not sink again to -$40. But as inventories rise, oil markets continue to test the realm of possibility. ■

Friday, April 24, 2020

The pandemic will leave the rich world deep in debt, and force some hard choices

how to pay for the war”, a pamphlet published in 1940, John Maynard Keynes looked back on the way that the British government had, in the late 1910s, tried to pay off enormous quantities of debt with a combination of higher taxes and inflation. Wages had not kept up with inflation, meaning “that consumers’ incomes pass[ed] into the hands of the capitalist class”. Meanwhile the rich, as bondholders, had benefited from interest on the loans.

This time, Keynes argued, it would be better to take money from the workers directly by forcing them to lend to the government while the war was on and there was little to spend money on anyway. Later the government could pay the workers back the money they had lent it with interest, using the proceeds of a substantial wealth tax. “I have endeavoured”, Keynes wrote, “to snatch from the exigency of war positive social improvements.”

Like a war, the fight against covid-19 has seen governments, particularly those in the rich world, rack up debts so large that the way in which they are paid off could have a long-lasting effect on their economies, and significantly affect the distribution of wealth. There are deep differences between today’s circumstances and those which Keynes surveyed, perhaps foremost among which is that advanced economies now routinely shoulder a level of debt that Keynes would have seen as an unmanageable burden (see chart 1). But those dealing with the aftermath of this year’s remarkable borrowing should still heed his example in looking for the right way to distribute the pain as they do so.

Debt before dishonour

The numbers involved are enormous. Advanced economies will run an average deficit this year of 11% of gdp, according to the imf, even if the second half of the year sees no more lockdowns and a gradual recovery. Rich-world public debt could run to $66trn, which might be 122% of gdp by year’s end.

Governments wishing to see such debt burdens diminish must tread one of three broadly defined paths. First, they can pay back the borrowing using taxation. Second, they can decide not to pay, or agree with creditors to pay less than they owe. Third, they can wait it out, rolling over their debts while hoping that they shrink relative to the economy over time.

The likely constraint on paying off debt with future tax revenues is politics. Such a strategy requires some mix of raising taxes—which upsets quite a few people—and cutting spending on other things—which also upsets quite a few people, including some who will not have liked the tax increases either. Nevertheless, after the global financial crisis of 2007-09, which increased debt levels by about a third in advanced economies, many countries chose to reduce public spending as a share of the economy. Between 2010 and 2019 America and the euro zone cut their public-spending-to-gdp ratios by about 3.5 percentage points. Britain’s fell by 6 percentage points. Taxation, meanwhile, rose by between 1 and 2 percentage points of gdp.

Public appetite for paying off pandemic debts through a return to such austerity seems likely to be scant. The emotional, as opposed to economic, logic of austerity—people had spent too much, and must rein themselves in—does not apply. What is more, post-covid publics are likely to want more spent on their health, not less. More than half of Britons supported tax increases that would pay for more spending on the National Health Service even before the pandemic struck. Ageing populations are also increasing the demand for public spending, as are investments needed to tackle climate change.

The second option—defaulting or restructuring debts—may be forced on to emerging economies which lack any other way out. If it is, that will cause significant suffering. In advanced economies, though, such things have been increasingly rare since Keynes’s day, and look unlikely to make a comeback. A modern economy integrated into global financial markets has a huge problem if capital markets lock it out as a bad risk.

That said, there may be more than one way to default. Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University argues that promises to increase health-care and pension spending in coming decades should also be viewed as government debt of a sort, and that this sort of debt is easier to back out of than obligations to bondholders. It is hard to ascertain whether the “default” risk in these debts—ie, the risk that politicians cut health-care and pension spending, reneging on their promises to ageing populations—is rising. Unlike bonds they are not traded on financial markets that provide signals of such things. But it almost surely is, especially in countries, like Italy, where pension spending is already enormous.

Rich-country politicians unwilling to shift away from spending and towards taxing, or to risk finding out how terrible a default would be, are likely to choose to grow their way out of hock. The secret to this is ensuring that the economy’s combined level of real economic growth and inflation stays handily above the interest rate the government pays on its debt. That allows the debt-to-gdp ratio to shrink over time.

In a much-noted speech in 2019 which called for a “richer discussion” about the costs of debt, Olivier Blanchard of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a think-tank, argued that such a strategy was more plausible than many might think. In the United States, he pointed out, nominal growth rates higher than interest rates are the historical norm.

Many rich-world governments pursued this sort of strategy after the second world war with some success. At its wartime height, America’s public debt was 112% of gdp, Britain’s 259%. By 1980 America’s debt-to-gdp ratio had fallen to 26% and Britain’s to 43%. Achieving those results involved both a high tolerance for inflation and an ability to stop interest rates from following it upwards. The second of these feats was achieved by means of a regulatory system which, by depriving citizens of better investment options, forced them in effect to lend to governments at low interest rates. By the 1970s economists were calling this “financial repression”.

In a paper published in 2015, Carmen Reinhart of Harvard University and Belen Sbrancia of the imf calculated that France, Italy, Japan, Britain and America spent at least half of that period in so-called “liquidation” years in which interest rates adjusted for inflation were negative. They estimated that the average annual “liquidation tax” to governments resulting from real interest kept low by inflation and financial repression ranged from 1.9% of gdp in America to 7.2% in Japan.

The violence inherent in the system

To attempt such repression today, though, would require redeploying tools used by post-war governments—tools such as capital controls, fixed exchange rates, rationed bank lending and caps on interest rates. This would be offensive to lovers of economic freedom. It would also be sufficiently contrary to the interests of investors and savers to be politically very demanding. That said, the coming years could prove to be politically demanding times. But if governments did enact such changes, they would spur responses unavailable to investors of the 1950s and 1960s, such as investment in cryptocurrencies and other immaterial products.

Even without a mechanism for keeping interest rates low, inflation can go some way to lessening the debt burden. “My gut instinct is that we will need higher inflation to wash away some of the debt,” says Maurice Obstfeld of the University of California, Berkeley (who, like Mr Blanchard and Mr Rogoff, was once chief economist at the imf). Yet though inflation may be necessary if debt burdens are to shrink, it may not be readily forthcoming. A few economists think inflation will surge of its own accord when the enormous economic stimulus they expect butts up against the supply disruptions imposed by lockdowns. But Mr Obstfeld and many others worry instead about deflation, or at least less inflation than they would like.

For some, the cause of this is “debt overhang”—the idea that debts sap the economy of demand. Wealthy bondholders, by definition, prefer saving to spending. Many others make a simpler judgment. The circumstances of the pandemic which made massive borrowing necessary in the first place—such as surging unemployment—are also likely to cause a deflationary slump. Since the pandemic started, the cost of insuring against inflation through financial markets has fallen, reflecting a belief that there is unlikely to be much of it about. Investors seem to be predicting that five to ten years from now the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank (ecb) and the Federal Reserve will all be undershooting their inflation targets.

Low inflation is bad for nominal growth. But it does at least reduce borrowing costs. Central banks can cut interest rates, if they have any room left to do so, and create money with impunity. In the five weeks leading up to April 16th, the Fed bought $1.3trn of American government debt: 5.9% of 2019 gdp and more than the entire budget deficit.

Thanks in part to the Fed’s actions, the American government can borrow for ten years at an interest rate of just 0.6%. In low-growth, lower-inflation Japan ten-year bonds are pegged at around 0%. Only in indebted countries in the euro zone, such as Italy, do bond yields threaten to exceed recent nominal growth rates.

These low interest rates make the fiscal picture seem less bleak. Vitor Gaspar, a senior official at the imf, says the fund expects a combination of low rates and rebounding growth to see debt burdens stabilise or decline in the “vast majority” of countries in 2021. And bond-buying by central banks takes much of the worry out of some of the debt.

Take Japan. Its gross-debt-to-gdp ratio in 2019 was around 240% of gdp, which sounds truly astonishing. But years of quantitative easing (qe) have left the Bank of Japan with government bonds worth nearly 85% of gdp. And the government could, in theory, sell financial assets of a similar magnitude if it had to. Adjust the debt to take these things into account and what remains is a little over 70% of gdp—less than a third of the gross figure and roughly comparable to what the figure is for America if you make the same adjustments (see chart 2).

Well before the pandemic such analysis had led many influential economists to start treating higher public debt as sustainable in a low-inflation, low-interest-rate world. Because the pandemic has pushed both inflation and interest rates the same way—down—their logic still holds. However, there are reasons for scepticism.

Start with central-bank debt holdings. qe does not really neutralise public debt. Central banks buy government bonds by creating new money which sits in the banking system in the form of reserves. And central banks pay interest on those reserves. Because the central bank is ultimately owned by the government, qe replaces one government debt-interest bill, interest payments on bonds, with another, interest payment on bank reserves. And although the latter are very low today—negative, in fact, in several places—they will stay so only so long as central banks do not need to raise rates to fight inflation.

Since the global financial crisis, betting on low rates has paid off; some have gone so far as to see them as a new normal, part of a low-growth economy in which demand needs constant stimulation. But that brings out another flaw in the sanguine view of public debt: it assumes that the future will be like the past. Although markets expect rates to remain low, it is not a sure thing. There is, for example, the possibility that lockdowns and stimulus in close succession do indeed bring on price rises. There is also the possibility that a great deal of the deflationary pressure has been due to oil prices, which as of today really do seem to have no further to fall.

An alternative critique is that the past may not offer the reassurance some might seek there. A preliminary working paper by Paolo Mauro and Jing Zhou of the imf, riffing on Mr Blanchard’s theme, examines borrowing costs and economic growth for 55 advanced and emerging economies over, in some cases, as much as 200 years.

The 24 advanced economies they study have on average benefited from interest rates which are below the nominal growth rate 61% of the time. Yet they find that such differentials are “essentially useless” for predicting sovereign defaults. “Can we sleep more soundly” with interest rates below growth rates? they ask. “Not really,” they answer.

The first sign of any debt trouble in the rich world would probably be rising inflation. At first, that might be a relief, given the present deflationary risk and the recent history of persistently insufficient inflation. It would be a sign that the economy was recovering. By reducing real interest rates it would further boost growth. And central banks that have long fallen a percentage point or so short of their inflation targets might feel comfortable seeing inflation ride a percentage point or so proud of it. But a somewhat relaxed attitude to 3% does not mean a willingness to accept 6%.

Inflation rising further above targets than it has been below them would bring on a stark choice for heavily indebted governments. Should they leave the central bank alone, let it raise rates to keep inflation at target, and look to taxpayers—or pensioners—to pay for the resulting rise in debt-interest costs? Or should they lean on their central banks to keep interest rates low, permitting inflation to rise and thereby easing their debt burdens?

Some context for that question comes from the blurring between fiscal and monetary policy the pandemic has already seen. Steve Mnuchin, America’s treasury secretary, has said that on some days he has spoken to Jerome Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve, more than 30 times. The Bank of England has co-ordinated interest-rate cuts with Britain’s treasury and recently agreed to increase the government’s overdraft. The Bank of Japan has long been an enthusiastic partner in the economic agenda of Abe Shinzo, the prime minister. The outlier is the euro zone where, because of the horror of inflation found in countries such as Germany and the Netherlands, political pressure on the ecb is just as likely to result in hawkish policy.

Facing the exigencies

Conveniently for politicians, some of the pain of high inflation would be borne by foreign investors, whose share of public debt exceeds 30% in many rich countries. “In a crunch, will Chinese debt-holders be treated as senior to us pensioners?” asks Mr Rogoff. But less foreign investment in years to come would need to be set against that advantage. A perception that a nominally independent central bank was in fact a creature of politicians would create a risk premium on investment that would slow growth throughout the economy.

Inflation would bring arbitrary redistributions of wealth to the disadvantage of the poor, just as Keynes observed it to have done in the late 1910s. Richer people are more likely to hold the houses and shares that rise in value with inflation, not to mention mortgages that would be inflated away alongside government debt. Higher inflation would also provide a bail-out that favoured more indebted companies over the less indebted.

Higher taxes, tried a little in the wake of the financial crisis, could be targeted more precisely to reduce inequality—much as they were in some countries after the second world war. Wealth taxes, as favoured by Keynes back then and increasingly discussed by academics and left-wing politicians today, could find that their time had come. Post-pandemic populations may welcome the sort of cost-free-to-most all-in-it-togetherness they might provide. Less radically, a value-added tax in America (which lacks one), higher taxes on land or inheritance, or new taxes on carbon emissions could be on the cards. Like inflation, however, tax rises inhibit and distort the economy while producing a backlash among those who must pay.

While the world’s chief problem is battling an economic slump in which inflation is falling, such choices are tomorrow’s business. They will not weigh heavily on policymakers’ minds. Even economists with reputations as fiscal hawks tend to support today’s emergency spending, and some want it enlarged. Yet one way or another, the bills will eventually come due. When they do, there may not be a painless way of settling them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)