When Dr. Tuomas Sandholm’s “Libratus” software defeated four champion poker players in Pittsburgh this February, it suggested that machine intelligence may have finally evolved to the level where it can excel in imperfect information scenarios.

The implications of this win and similar advancements are widespread, and when coupled with the steadily increasing prevalence of ‘big data’ and alternative data sets in investing, suggest that the active management investment universe is undergoing a dramatic evolution.

To better understand the resurgence of interest in the systematic hedge fund (HF) space, from the perspective of both managers and investors, our Strategic Consulting team analyzed data from 64 hedge funds across systematic, discretionary, and hybrid strategies; and 25 investors representing ~$240bn in total HF assets. The objective was to present an overview of the growth trajectory and business/product mix of systematic hedge fund strategies; measures of systemic risk; fund performance across market conditions; and the use of big data throughout the investment process.

Systematic Strategies within the Hedge Fund Industry

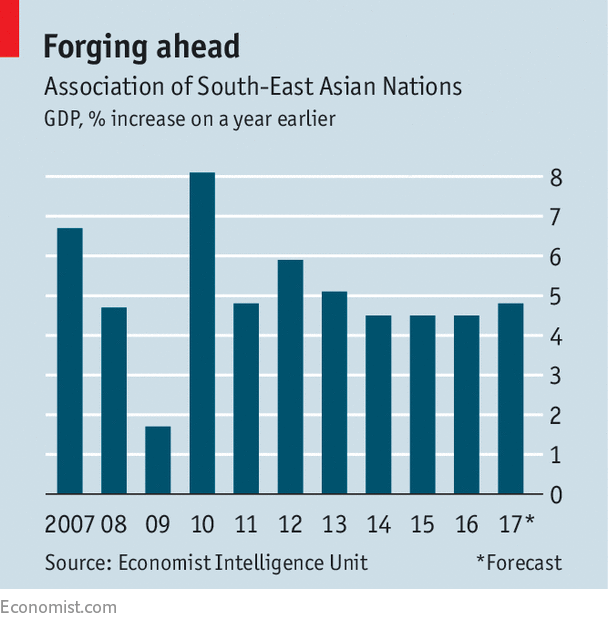

The study estimates the “systematic strategies” segment of the hedge fund industry at roughly 17% of the total industry size, comprising approximately $500 billion in assets under management, the bulk of which (~$450bn) is found in stand-alone systemic products and the remainder of which (~$55bn) are allocations within larger discretionary multi-strategy funds.

Size of Systematic Strategies within the HF Industry

Source: 2017 HFI, HFR, review of manager marketing materials and publicly available documents, Strategic Consulting analysis.

* CTA – Commodity Trading Advisor; ** We estimate that 70-80% of these strategies are managed futures, with the remainder in EMN.

The Strategic Consulting team also found a meaningful increase in investors’ levels of comfort with systematic strategies in recent years. Traditionally, systematic strategies have been more difficult to understand and less conducive to transparency as a result of their secrecy and/or complexity. However, this greater acceptance of systematic strategies has been a driver of inflows to systematic managers.

Comfort with Allocations to Systematic Strategies

Source: 2017 Strategic Consulting analysis; 2015 data from Strategic Consulting Report “Bracing for Impact” and 2016 / expected 2017 data from Strategic Consulting report “Turning the Tide” .

At the same time, this growth has led to concerns around crowding in equity quant strategies in particular and the potential for another 2007-style ‘quant crash’. That said, the team’s measures of risk suggest that these concerns may be overblown.

Big Data and Machine Learning

Recent advancements in ‘big data’ and ‘machine learning’ have also driven change in how systematic managers incorporate data, technology and analytics in their investment process. The Strategic Consulting team found that 54% of the systematic managers in their sample are now employing alternative and ‘big data’ sources such as web scraping (i.e., a technique to extract large amounts of data from websites, social media data, satellite data and credit card data). Additionally, 62% of the systematic managers are using machine learning techniques within the investment process.

'Big Data' - Current Usage

Source: 2017, 1. Strategic Consulting survey results and analysis (3Q16-1Q17) – refers to % of interviewed managers incorporating each data source in their research process. 2. IDC

Among discretionary managers, 24% are using ‘big data’ and approximately 50% have incorporated quantitative techniques across the information gathering, idea generation, portfolio construction / risk management, and performance analysis components of the investment process.

Quantamental - Use of 'Big Data', Quant Techniques

Source: 2017 Strategic Consulting survey results and analysis (3Q16-1Q17)

1. Range of 45%-55% covers responses across all four categories (info gathering, idea gen, port construction / risk mgt, performance analysis)

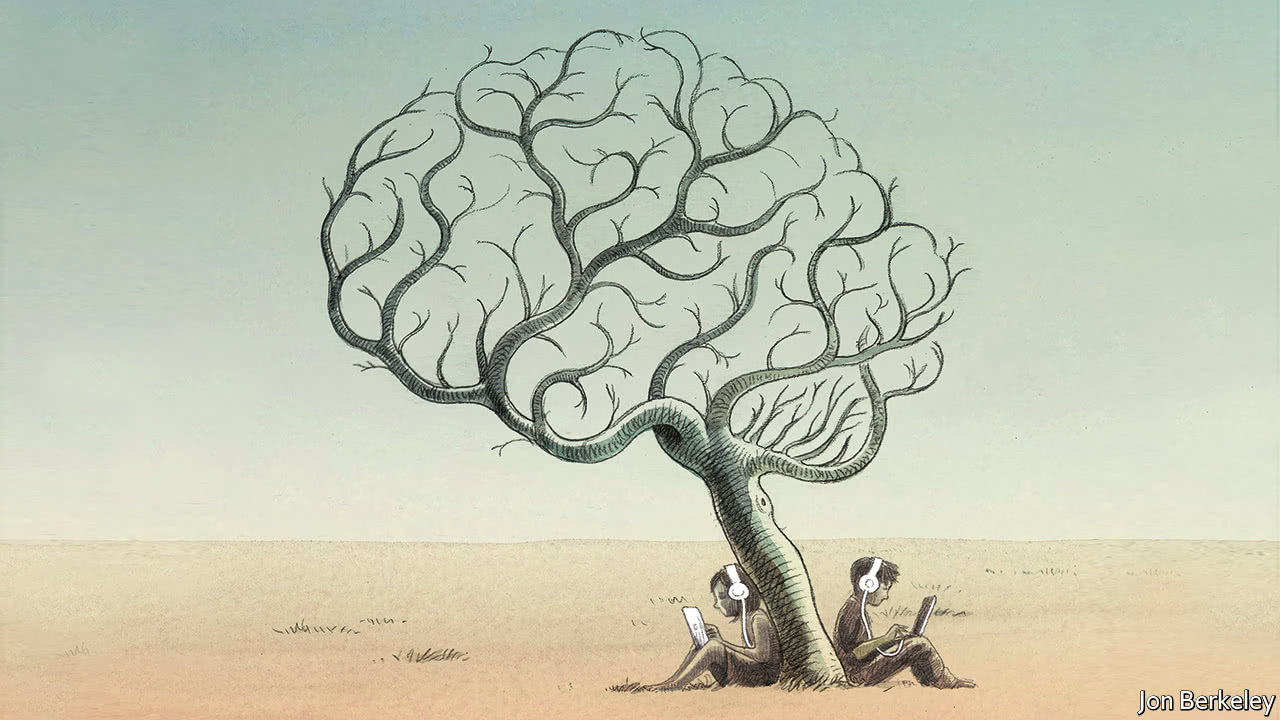

Final Considerations

In general, while the expectation of the managers and investors interviewed was that systematic strategies and techniques will continue to grow in importance within the hedge fund industry, the team found that there are areas where human judgment is likely to retain the advantage for the foreseeable future, and a hybrid approach – a blend of systematic and discretionary approaches – may well be the most popular in the long-term.