In October 1990, Simon found a check for $576.07 in his mailbox. Ehrlich got smoked. The price of every one of the metals had declined. In the 1960s, 50 out of every 100,000 global citizens died annually from famine; by the 1990s, that number was 2.6.

Ehrlich’s starvation predictions were almost comically bad. And yet, the very same year he conceded the bet, Ehrlich doubled down in another book, with another prediction that would prove untrue: Sure, his timeline had been a little off, he wrote, but “now the population bomb has detonated.” Despite one erroneous prediction after another, Ehrlich amassed an enormous following and received prestigious awards. Simon, meanwhile, became a standard-bearer for scholars who felt that Ehrlich had ignored economic principles. The kind of excessive regulations Ehrlich advocated, the Simon camp argued, would quell the very innovation that had delivered humanity from catastrophe. Both men became luminaries in their respective domains. Both were mistaken.

When economists later examined metal prices for every 10-year window from 1900 to 2008, during which time the world population quadrupled, they saw that Ehrlich would have won the bet 62 percent of the time. The catch: Commodity prices are a poor gauge of population effects, particularly over a single decade. The variable that both men were certain would vindicate their worldviews actually had little to do with those views. Prices waxed and waned with macroeconomic cycles.

Yet both men dug in. Each declared his faith in science and the undisputed primacy of facts. And each continued to miss the value of the other’s ideas. Ehrlich was wrong about the apocalypse, but right on aspects of environmental degradation. Simon was right about the influence of human ingenuity on food and energy supplies, but wrong in claiming that improvements in air and water quality validated his theories. Ironically, those improvements were bolstered through regulations pressed by Ehrlich and others.

Ideally, intellectual sparring partners “hone each other’s arguments so that they are sharper and better,” the Yale historian Paul Sabin wrote in The Bet. “The opposite happened with Paul Ehrlich and Julian Simon.” As each man amassed more information for his own view, each became more dogmatic, and the inadequacies in his model of the world grew ever more stark.

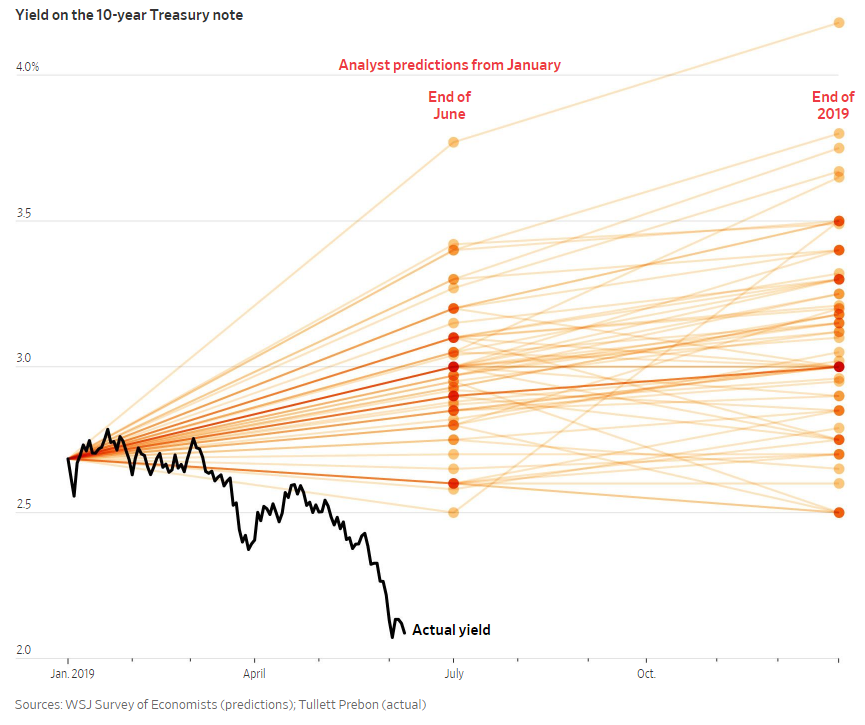

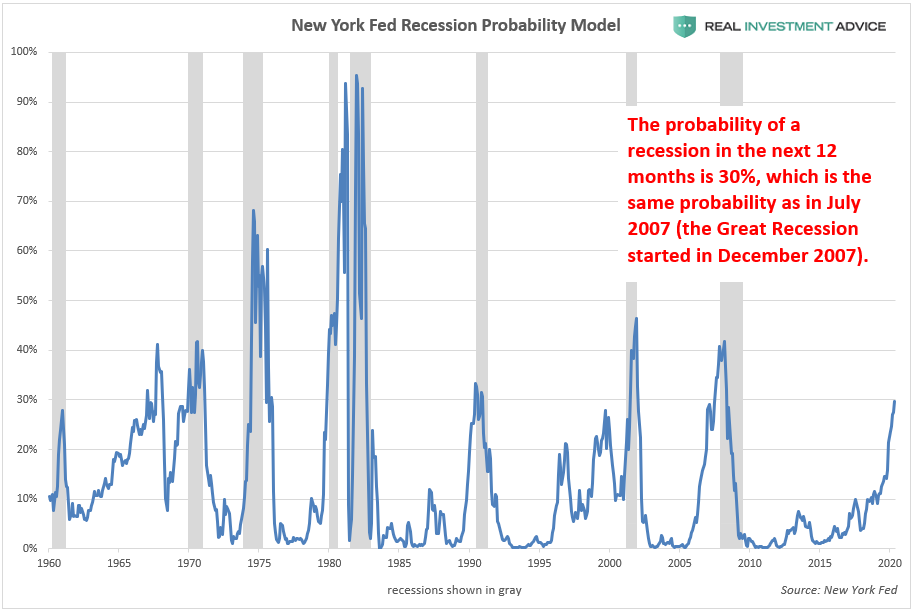

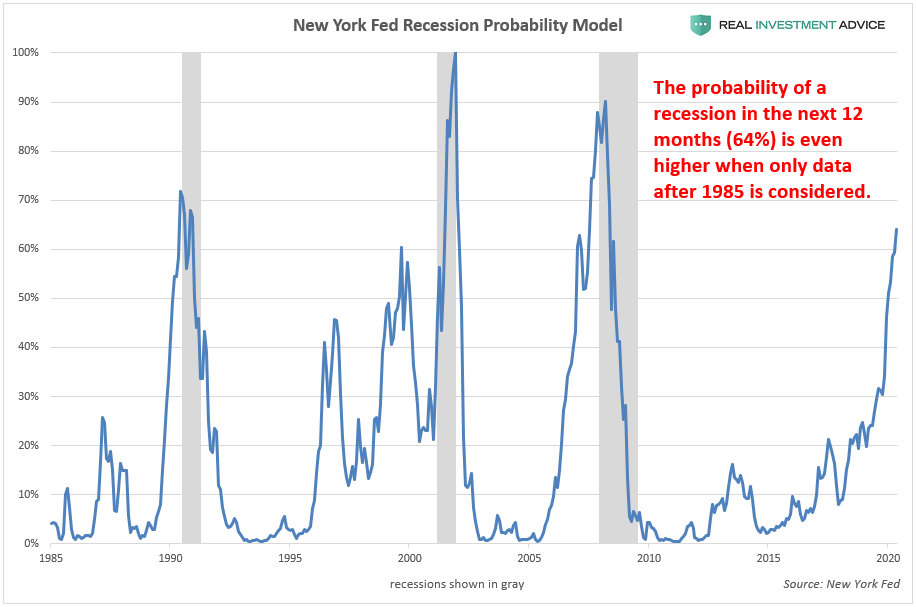

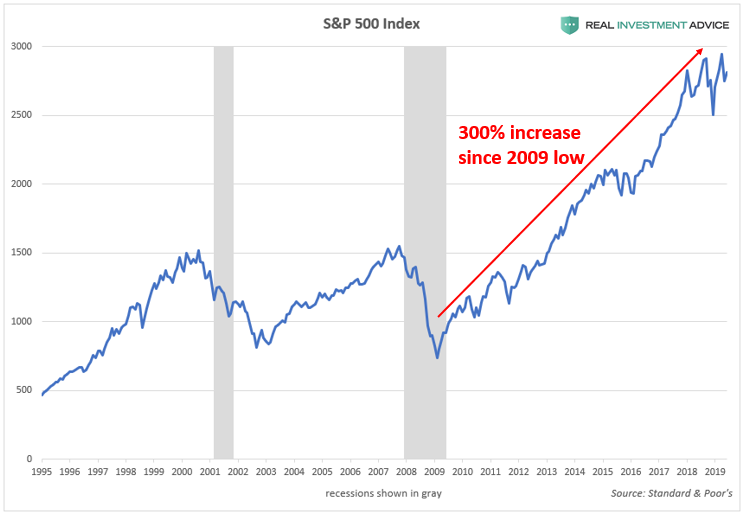

The pattern is by now familiar. In the 30 years since Ehrlich sent Simon a check, the track record of expert forecasters—in science, in economics, in politics—is as dismal as ever. In business, esteemed (and lavishly compensated) forecasters routinely are wildly wrong in their predictions of everything from the next stock-market correction to the next housing boom. Reliable insight into the future is possible, however. It just requires a style of thinking that’s uncommon among experts who are certain that their deep knowledge has granted them a special grasp of what is to come.

The idea for the most important study ever conducted of expert predictions was sparked in 1984, at a meeting of a National Research Council committee on American-Soviet relations. The psychologist and political scientist Philip E. Tetlock was 30 years old, by far the most junior committee member. He listened intently as other members discussed Soviet intentions and American policies. Renowned experts delivered authoritative predictions, and Tetlock was struck by how many perfectly contradicted one another and were impervious to counterarguments.

Tetlock decided to put expert political and economic predictions to the test. With the Cold War in full swing, he collected forecasts from 284 highly educated experts who averaged more than 12 years of experience in their specialties. To ensure that the predictions were concrete, experts had to give specific probabilities of future events. Tetlock had to collect enough predictions that he could separate lucky and unlucky streaks from true skill. The project lasted 20 years, and comprised 82,361 probability estimates about the future.

The result: The experts were, by and large, horrific forecasters. Their areas of specialty, years of experience, and (for some) access to classified information made no difference. They were bad at short-term forecasting and bad at long-term forecasting. They were bad at forecasting in every domain. When experts declared that future events were impossible or nearly impossible, 15 percent of them occurred nonetheless. When they declared events to be a sure thing, more than one-quarter of them failed to transpire. As the Danish proverb warns, “It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.”

Even faced with their results, many experts never admitted systematic flaws in their judgment. When they missed wildly, it was a near miss; if just one little thing had gone differently, they would have nailed it. “There is often a curiously inverse relationship,” Tetlock concluded, “between how well forecasters thought they were doing and how well they did.”

Early predictions in Tetlock’s research pertained to the future of the Soviet Union. Some experts (usually liberals) saw Mikhail Gorbachev as an earnest reformer who would be able to change the Soviet Union and keep it intact for a while, and other experts (usually conservatives) felt that the Soviet Union was immune to reform and losing legitimacy. Both sides were partly right and partly wrong. Gorbachev did bring real reform, opening the Soviet Union to the world and empowering citizens. But those reforms unleashed pent-up forces in the republics outside Russia, where the system had lost legitimacy. The forces blew the Soviet Union apart. Both camps of experts were blindsided by the swift demise of the U.S.S.R.

One subgroup of scholars, however, did manage to see more of what was coming. Unlike Ehrlich and Simon, they were not vested in a single discipline. They took from each argument and integrated apparently contradictory worldviews. They agreed that Gorbachev was a real reformer and that the Soviet Union had lost legitimacy outside Russia. A few of those integrators saw that the end of the Soviet Union was close at hand and that real reforms would be the catalyst.

The integrators outperformed their colleagues in pretty much every way, but especially trounced them on long-term predictions. Eventually, Tetlock bestowed nicknames (borrowed from the philosopher Isaiah Berlin) on the experts he’d observed: The highly specialized hedgehogs knew “one big thing,” while the integrator foxes knew “many little things.”

Hedgehogs are deeply and tightly focused. Some have spent their career studying one problem. Like Ehrlich and Simon, they fashion tidy theories of how the world works based on observations through the single lens of their specialty. Foxes, meanwhile, “draw from an eclectic array of traditions, and accept ambiguity and contradiction,” Tetlock wrote. Where hedgehogs represent narrowness, foxes embody breadth.

Incredibly, the hedgehogs performed especially poorly on long-term predictions within their specialty. They got worse as they accumulated experience and credentials in their field. The more information they had to work with, the more easily they could fit any story into their worldview.

Unfortunately, the world’s most prominent specialists are rarely held accountable for their predictions, so we continue to rely on them even when their track records make clear that we should not. One study compiled a decade of annual dollar-to-euro exchange-rate predictions made by 22 international banks: Barclays, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, and others. Each year, every bank predicted the end-of-year exchange rate. The banks missed every single change of direction in the exchange rate. In six of the 10 years, the true exchange rate fell outside the entire range of all 22 bank forecasts.

In 2005, tetlock published his results, and they caught the attention of the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity, or IARPA, a government organization that supports research on the U.S. intelligence community’s most difficult challenges. In 2011, IARPA launched a four-year prediction tournament in which five researcher-led teams competed. Each team could recruit, train, and experiment however it saw fit. Predictions were due at 9 a.m. every day. The questions were hard: Will a European Union member withdraw by a target date? Will the Nikkei close above 9,500?

Tetlock, along with his wife and collaborator, the psychologist Barbara Mellers, ran a team named the Good Judgment Project. Rather than recruit decorated experts, they issued an open call for volunteers. After a simple screening, they invited 3,200 people to start forecasting. Among those, they identified a small group of the foxiest forecasters—bright people with extremely wide-ranging interests and unusually expansive reading habits, but no particular relevant background—and weighted team forecasts toward their predictions. They destroyed the competition.

Tetlock and Mellers found that not only were the best forecasters foxy as individuals, but they tended to have qualities that made them particularly effective collaborators. They were “curious about, well, really everything,” as one of the top forecasters told me. They crossed disciplines, and viewed their teammates as sources for learning, rather than peers to be convinced. When those foxes were later grouped into much smaller teams—12 members each—they became even more accurate. They outperformed—by a lot—a group of experienced intelligence analysts with access to classified data.

One forecast discussion involved a team trying to predict the highest single-day close for the exchange rate between the Ukrainian hryvnia and the U.S. dollar during an extremely volatile stretch in 2014. Would the rate be less than 10 hryvnia to a dollar, between 10 and 13, or more than 13? The discussion started with a team member offering percentages for each possibility, and sharing an Economist article. Another team member chimed in with historical data he’d found online, a Bloomberg link, and a bet that the rate would land between 10 and 13. A third teammate was convinced by the second’s argument. A fourth shared information about the dire state of Ukrainian finances, which he feared would devalue the hryvnia. A fifth noted that the United Nations Security Council was considering sending peacekeepers to the region, which he believed would buoy the currency.

Two days later, a team member with experience in finance saw that the hryvnia was strengthening amid events he’d thought would surely weaken it. He informed his teammates that this was exactly the opposite of what he’d expected, and that they should take it as a sign of something wrong in his understanding. (Tetlock told me that, when making an argument, foxes often use the word however, while hedgehogs favor moreover.) The team members finally homed in on “between 10 and 13” as the heavy favorite, and they were correct.

In Tetlock’s 20-year study, both the broad foxes and the narrow hedgehogs were quick to let a successful prediction reinforce their beliefs. But when an outcome took them by surprise, foxes were much more likely to adjust their ideas. Hedgehogs barely budged. Some made authoritative predictions that turned out to be wildly wrong—then updated their theories in the wrong direction. They became even more convinced of the original beliefs that had led them astray. The best forecasters, by contrast, view their own ideas as hypotheses in need of testing. If they make a bet and lose, they embrace the logic of a loss just as they would the reinforcement of a win. This is called, in a word, learning.