By Anand Sanwal (@asanwal), CEO and co-founder of CB Insights.

From tech in NYC to chemical manufacturing in Nasik (India), here's a guide that hopefully nobody ever needs.

On April 17, 2017 my dad died.

It was the worst day of my life.

It was also the day I started to lead a second company – his company. (Note: the first company is CB Insights.)

His company was in India (a country I knew little about) in the chemical manufacturing industry (an industry I knew nothing about).

On June 1st, 2018, after running his company for 13 months, it was acquired.

While I don’t think most people would ever find themselves in a similar situation (I certainly hope not), I thought I’d share the story and some of my learnings & observations from that time about business, M&A, teams, India, and assorted miscellaneous thoughts.

Life comes at you fast

As I was going with family to cremate my father in a traditional Hindu funeral, someone who I didn’t know came up to me and said in Hindi, “Saab, humara kya hoga?”

That translates to “Sir, what will happen to us?”

I didn’t know who it was.

I assumed it was a worker from my Dad’s factory.

I was a mess at the time.

And I remember thinking to myself, “Why the F are you asking me about this right now?”

But this wasn’t the time for anger or to even to think about this so I just knee-jerk responded in my heavily American-accented Hindi that “Meh dekh loonga” which translates to “I’ll look after it.”

And so at that point, in addition to CB Insights, I knew I was going to run my Dad’s business. To be honest, I had already thought about this possibility when he was admitted to the hospital when the doctors said the situation was looking dire.

But no matter my age, Dad was always the strongest, smartest person I knew, and so I assumed he’d pull through and things would go back to normal. With him tirelessly working on Atlas, the company he founded, and me going back to CB Insights.

But then April 17th happened.

And now, I was going to run his business.

I was going to run Atlas.

I wasn’t ready for this.

Before we go further, a bit of context on Atlas, my Dad’s business.

The company was recently renamed AIMS Impex, but it started and for most of its life, it was known as Atlas Fine Chemicals. Industry folks know it as Atlas, and my sisters and I grew up knowing it under that name so I will refer to it as Atlas going forward.

Atlas is a manufacturer of specialty flavor & fragrance chemicals such as coumarin, 6-methyl coumarin, safranal, natural vanilla, and cyclocitral among others. Atlas’ customers include the world’s largest flavor & fragrance houses including IFF, Givaudan, Firmenich, Takasago, and Symrise among others.

Atlas is based 4 hours from Mumbai in a city called Nasik (1.486 million people) and the manufacturing facility is about 35 minutes from Nasik in a small village called Sinnar.

If there ever was a polar opposite to CB Insights, it’s Atlas.

CB Insights is a technology company.

Atlas is an industrial manufacturing company.

(note: more on the differences below)

But here we were.

Day 1 in my new gig

I don’t remember the exact day I went to the office for the first time as the weeks after April 17th were a blur of family, tradition, and emotion.

Before even stepping foot in the office, I had asked the team to send me the reports they sent to Dad so I could get familiar with the business.

TBH, I didn’t know what I’d do with these reports, but I figured that acting like I knew what I might be doing might provide some confidence to the team.

Candidly, my only qualification to run Atlas at this time was that I was the founder’s son.

I had tried to be the good Indian son back in 1998-2000 and work at Atlas so knew the biz a bit in its earlier days, but 18 years is a long time for a business and my mind was jammed with all sorts of other experiences and ideas since then. My time at Atlas was just a distant memory.

In 1998, moving from the fun of NYC to small town India was tough especially as someone born and brought up in the US. Moreover, I was a know-it-all who had all the answers despite just graduating from college and so my dad’s inability to recognize my genius bothered me.

And so after 18 months working with Dad, I left to join Kozmo.com.

I still wonder what Atlas might have become if I could have figured out how to be more of a student and less of an Ivy League douche when I was working with my dad back then. What kind of duo might we have been?

So, in a strange and sad way, this was an opportunity to finally be the good Indian son and run Dad’s business.

In late April, I finally went to the office.

When I entered, everyone stood up to greet me.

Nobody called me Anand.

I was referred to as Sir, which is what everyone referred to my father as.

Yup — this felt strange.

I remember thinking this was odd at the time, and during all my visits to the office subsequently, but in many ways, this sort of cultural deference to the unqualified boss’ son is what enabled Atlas to carry on.

I imagine if the same had happened in the US, there would have been many more questions about my qualifications and capabilities. At Atlas, those conversations might have very well happened, but I doubt it. Or, if they did, these questions weren’t directed to me. I got lucky here.

Everyone, for better or worse, assumed I had a clue and was looking for me to develop a plan.

What the F is the plan?

So I needed a plan.

Not on day 1, but pretty quickly.

Not because anyone was asking for one, but for myself. For Atlas.

How does one develop a plan when you don’t understand the business, the science, the industry, the country, and sometimes even the language? (I have passable Hindi but a lot of the local conversations at Atlas were in Marathi which I don’t understand.)

In my view, there were 4 options for the business.

Option 1 — Run the business and become this huge multi-industry conglomerate

I entertained Option 1 for about 6 weeks. The ill-conceived idea was that I’d figure out how to run both Atlas and CB Insights, going forward with Atlas as the beachhead for a larger industrials business and CB Insights as the first part of a massive technology arm.

Visions of grandeur and all that good stuff.

This was some stupid, naive thinking.

In India, you see all these families (Ambani, Birla, Tata, Godrej, Hinduja, etc) who are in every potential business line possible. I figured they all started somewhere. Maybe this would be my starting point.

After about 6 weeks of trying to be present at CB Insights, but doing calls every morning at 6am with the Atlas team and emails every evening responding to the team or to Atlas customers, it became apparent that Option 1 wasn’t feasible.

I kept this 6am morning call/evening email routine going for the last 13 months with CB Insights occupying the middle of the day and every other minute of idle brain time. Needless to say, I’ve aged immeasurably in the last 13 months. My desire to build a multi-industry conglomerate died because the idea was just too tiring.

Option 2 — Sell the company for its parts

For a second, I looked at what the company might fetch for its assets. Its land, plant, etc.

I’d never done something like this but I remember hearing about it when Gordon Gecko talked about it in the movie Wall Street so figured, why not?

If the strategy works in movies, it must work in real life too, right?

But this wasn’t a real option ever and was discounted in a few hours.

My dad built this company over 30 years with many of his team having been with him for 20+. Selling the company’s assets, even if feasible, would be me failing his team and him.

Not going to happen.

Option 3 — Find a young, aggressive, ambitious person to run Atlas

The third idea was to see if there was someone who could run Atlas with some guidance from Dad’s team and me (assuming I could eventually understand the business). And then give this person the ability to earn more and more equity over time.

Essentially, they’d run the company and eventually own it.

This idea was appealing as it’d let my family continue to be involved with the business while also finding someone capable to take it to the next level.

The problem here was that I had no network in India from which to even think about finding someone for this role. I spoke with a couple of candidates via introductions but nothing really stuck for them or me. Moving to Nasik was a challenge even for those in India, but that was just a symptom of not finding the right person.

This would have been an amazing opportunity for the right person, but it wasn’t in the cards.

Option 4 — Run the business until a buyer can be found

Option 4 was ultimately the most practical.

The challenge, however, was that Dad’s business didn’t have too many natural buyers and was considered a small market transaction making it even tougher.

And so I didn’t have any control on the M&A side of things.

I focused on running the business and hoped a suitable acquirer would show up. If nobody showed up, I’d keep running it.

I gave myself 3 years to run both Atlas and CB Insights, thinking I could maintain the daily schedule of 6am calls and evening emails with India interspersed, with trips every 6-8 weeks before burning out. 3 years was a completely arbitrary timeline.

About 6 months in, I realized doing both for that long really wasn’t sustainable for a number of reasons — health, family, and it wasn’t optimal for either CB Insights or Atlas.

But I didn’t know the buyer market and couldn’t control it so I focused on what I could control.

And that was running Atlas.

Running a business you know nothing about

Despite Atlas being very different than CB Insights, the answer about how to run it came to me easier than a lot of the other questions I had over the last 13 months.

Or perhaps I just oversimplified it to make a decision quickly.

I decided that business is about growth or margin.

To grow, we could do 1 of 2 things:

- Sell more of our existing products — primarily Coumarin

- Add new products

If we focused on margin, that’d mean focusing on:

- Increasing efficiency in manufacturing

- Reducing expenses

I looked at the financials for Atlas vs peers in the industry and talked to some of my dad’s trusted advisors, and it was apparent that Atlas’ margins were best-in-industry.

Dad was the ultimate bootstrapper.

Atlas was efficient, and my dad obsessed about margins, foregoing business that was low margin to keep overall profit margins high.

It was clear that focusing on the margin side wasn’t the best place for my time or energy.

Plus, most of the efficiency to be gained was in the manufacturing process and that is where I was zero value-add. Dad was also the ultimate technical co-founder. I was as non-technical as they come in a chemical manufacturing setting.

Plus, margin is hard to rally the team around.

Growth is tangible.

And I needed to paint a picture that the team could see. Improving margin by XX basis points wasn’t going to be what got anyone fired up.

So I decided to focus on growth. Growth not via new products as that would also require Dad, the technical co-founder.

I focused on growth of Coumarin — the company’s primary product.

This was also the only way to run the company that I had a chance of being useful in.

And it was also the way I could show the Atlas team we were doing well. And that I might have some value beyond being the boss’ son.

Selling is something everyone sees, especially in a manufacturing setting. From the workers at the factory to the plant staff, if they see trucks coming in for product dispatches, they know the product they’re making is selling. If the staff in the office is busy generating invoices and fielding customer calls, they see the product is selling.

And while I’m by no means a natural at selling, if armed with the right product, I can sell. And Atlas’ Coumarin was the best in the world.

In the chemical industry, it’s unheard of to be a single product company for 30 years. But Atlas was able to do that because the product is hard to make, and they are the best at it.

So growth it was.

Note: It is worth noting that in a competitive chemical product, margins cannot be ignored. So while growth was the focus, I did focus on major expenses — raw materials, shipping, packaging. But this was only 5% of my time as the very capable team at Atlas managed these expertly.

Growth the old-fashioned way — cold calling and cold emailing prospects and customers

So with growth being the focus, I went about assembling a list of people and firms in the industry I should reach out to.

I went through my dad’s emails to see who he’d interacted with and reached out to all of them.

I visited various fragrance and flavor association and conference websites and took down their member and attendee names and reached out to them.

It wasn’t a particularly structured process, but I wanted those that knew my dad to know that Atlas was still humming and they could rely on us for product.

And for those that didn’t know us, the next time they had a need, they knew they could reach out to us.

This was a lot of cold emailing and cold calling. I have heightened respect for what SDRs do at CB Insights or anywhere. It is hard work. But also incredibly rewarding when someone closes based on your efforts.

At the same time, I also focused on price. Dad had built a high margin business which afforded me the opportunity to try to gain market share by being more aggressive with price.

Coumarin is probably a 6,000 ton product per year. Atlas was about 10-12% of the global market, but we had capacity at the plant that wasn’t being used so I knew we could produce and sell more. There is some supply-demand curve, marginal cost calculation I could have done here, but I didn’t do any of that.

I did some back of the envelope math in my head and had worked out a simple, rudimentary cost per kg formula in Excel to ensure we were always making something on a sale, but I ran Atlas on instinct a lot more than analysis.

Atlas has a great team with lots of experience. I assumed if I was doing something really really dumb, they’d tell me 🙂

In the last financial year (April 2017-March 2018), Atlas had its best revenue in history. In November 2017, we dispatched 100 tons of Coumarin to customers for the first time in the company’s history.

I remember taking mithai (sweets) to the site at the end of November when the 100 ton month happened and celebrating with the team. It was one of the proudest days I’ve ever had professionally. I was incredibly proud of the Atlas team who had seen a potentially company-sinking event happen with my dad’s death in April and who’d kept fighting and doing good work and then just had a historic month.

So, things were going well with the company.

What about a buyer?

The M&A buyers show up

As soon as I took over the business, the calls started coming from interested buyers or their investment banks.

Dad had already been in discussions with 1 firm prior to his death, and I’d met them once with him. They re-engaged.

The flavor & fragrance industry in India is big, but small at the same time.

Everyone learned about Dad’s passing pretty quickly.

As a result, various buyers expressed interest. I reached out to a couple of our large customers to feel them out.

By the end of July, I had a group of buyers identified.

I had done some basic research on the space so I understood the players and sounded at least reasonably smart. A report by investment bank Avendus on the flavor & fragrance industry was useful for a novice like me. Atlas was a base ingredient manufacturer. Our likely buyers were either larger base ingredient manufacturers or functional ingredient manufacturers who were interested in vertical integration.

There were 5 buyers that either came to us or that I’d identified and gotten some expression of interest from.

- Buyer 1 – A publicly traded Indian firm that also makes Coumarin at much smaller volumes

- Buyer 2 – An Atlas client who was interested in potential vertical integration

- Buyer 3 – A wealthy family looking to buy a business for their son returning from the US

- Buyer 4 – A private-equity backed chemical company

- Buyer 5 – A family-held chemical company that also manufactured Coumarin

Most of these buyers did not get very far.

But I had conversations with all of them.

Before digging into how things went with each buyer, it is worth understanding that there were certain criteria I had for a deal which made eliminating certain buyers easy.

My 3 deal criteria were simple:

- They had to take care of the team — I wanted to find a growth-oriented company as ensuring the team that had helped build Atlas would be taken care of was critical. The biggest factor in any decision was this as I viewed it as intertwined with my dad’s legacy. He spent 30 years building this company with this team. It was important that this be maintained and hopefully taken to the next level. There is, of course, no way to know this for sure and this is where one’s gut and how the buyer across the table makes you feel is important.

- Simple deal — I was not interested in stock in a private company or an illiquid public company or a long earn-out or some other complex structure. Atlas wouldn’t be a big deal for any credible buyer. Complexity wasn’t required. I also didn’t have time to educate a buyer on the space.

- A fair price — When the founder/face of a company dies (my dad), a bunch of bottom feeding parasites can show up. I wasn’t expecting to get a top of the market price for Atlas, but I wanted a fair one. Moreover, the longer I ran Atlas, the more confident I became in my ability to run it. So the price was only going to go up with time.

So now let’s look at each potential buyer.

Buyer 1 — A publicly traded Indian firm that also makes Coumarin at much smaller volumes

I met with one of the execs of this firm along with their investment bank once.

I shared high-level data on Atlas with them but the conversation ended after that. They were saddled with lots of debt as I could see given they were public and so didn’t think a deal with them would meet the criteria I had on fair price, simplicity, or even ability to take care of the team.

Not a good fit.

One conversation and things were done.

Buyer 2 — An Atlas client who was interested in potential vertical integration

This was a client I’d reached out to.

They were interested in Atlas. We talked a bit and they proposed a deal, but the structure was complicated and so I let this one go. They are a long-standing client and we were far enough away from any deal that it didn’t make sense to engage further.

Buyer 3 — A wealthy family looking to buy a business for their son returning from the US

This was an introduction from one of my dad’s advisors.

They were a family with a large industrial business and were interested in expanding into new lines as their son was returning to India from the US. (I guess really wealthy people do things like this).

They were super smart and impressive.

The challenge here was that it’d require lots of education about the industry and the probability of success even after investing would be low.

This wasn’t time I had.

After a couple of conversations, it was clear this wasn’t a fit.

Buyer 4 — A private-equity backed chemical company

This was the firm my dad was already in discussions with. The firm had seen Atlas’ numbers and had actually given an offer to my dad prior to his death. They seemed the most promising at the outset given the diligence they’d already done.

So I met them in May before leaving India.

It was an interesting meeting.

For an hour, they told me all the reasons Atlas wasn’t a great business. I listened as I’m probably too deferential to those older than me than I should be.

And after listening for a while, I asked them, “You’ve told me all the reasons Atlas is such a bad company. So why do you want to acquire it?”

That seemed to reset the conversation a bit.

Ultimately, there wasn’t a fit.

Part of this may have been culture fit and part of this was likely ownership by PE which complicated decision-making on their side. It’s important to understand the decision-making criteria and process of a buyer when discussing M&A.

The firm wanted to follow their process.

I told them that process didn’t work for Atlas or me or my family. And I told them that process was what we needed to run. When they said no, I wished them luck and moved on.

I was nervous doing this tbh. There wasn’t a huge list of buyers for Atlas and shutting one of them out seemed at times like it might be foolish. But you have to go with your gut on these things.

Life went on.

Buyer 5 — A family-held chemical company that also manufactured Coumarin

Buyer 5 reached out via the company’s investment banker.

I’d received lots of calls from bankers prior and I insisted they tell me who they were representing as many were just fishing.

Buyer 5’s banker revealed the company’s name.

I knew my dad had had conversations with them some years ago.

We met in July and there was immediately a better fit.

I explained my criteria, they explained their vision, they put a non-binding offer together that was clean/clear and we got moving on diligence.

The rest is history.

June 1st — Atlas is officially sold

On May 31st, I flew back to India. It was my 8th trip in the last 13 months.

I landed at 10pm. The offices of Avendus, the investment bank representing Eternis, the buyer, was the first destination.

I arrived at 11pm and we worked until 5am to hash out final details of the deal.

We went away for 4.5 hours to shower and get some sleep and resumed at Eternis’ office at 930am on June 1st. By 4pm that day, the deal was done.

At 5pm, I left Mumbai for the 4-hour drive to Nasik.

The news broke within the industry pretty quickly. During the 4-hour drive to Nasik, folks started calling and WhatsApp messaging me — customers, vendors, etc.

And so did the Atlas team.

I’d only disclosed the deal conversation to 4 people at Atlas prior.

I was hoping to tell the team on Saturday (6 day workweek at Atlas) in the office so I felt bad that some of them heard about the deal on Friday evening through others.

The next day, I went to the factory and members of the Eternis team came. Manu of the Eternis team addressed the office and factory staff and gave a great view into their goals and their company.

The official farewell

On June 4th, we decided that our family would officially say farewell to the entire Atlas team at the factory. We had everyone from the office come up.

My mom, kids, and wife flew in from the States. I wanted my kids to see what their “Dada” (grandfather) had built at least 1 time before it moved onto the next chapter in its story.

And we wanted to say thanks to everyone on the Atlas team.

I had prepared a speech in English and my wife translated it to Hindi. My Hindi is not very good so beyond the emotion of this farewell, I was pretty scared of delivering a several minute speech in Hindi. I’d never done something like that.

We assembled in the warehouse, and I stood on top of the chemical mixer and talked to the team. I fought back tears several times during my speech. My Hindi was intelligible enough that I had several others on the Atlas team also crying so I guess that my message was understood.

My speech in English is below. It was delivered in Hindi, and the video is something I hope to show my kids when they are old enough to understand.

Speech:

My Hindi is not very good so please forgive me if I make any mistakes.

Dad started Atlas 29 years ago. As my sisters and I were growing up, we joked that Atlas was his 4th child.

But in reality, Atlas was less of a 4th child than a 2nd family to Dad.

He loved working with you all. Whether it was increasing production or improving our Sali to Coumarin yield or solving technical challenges to figuring out how to keep Chinese Coumarin out of India to showing the plant to foreign visitors, there was nothing he liked more.

And together with Dad, you all built something very special.

Many of you have been with Dad for 20+ years. He and you grew up and built Atlas together.

And now, Atlas Coumarin is known globally for being the highest quality coumarin in the world. All the leading multinational companies like IFF, Givaudan, Firmenich rely on Atlas.

Within India, Atlas Coumarin has more than 50% of the market.

And now, there are a group of new products such as 6-methyl coumarin, safranal, and cyclocitral which can make Atlas even bigger.

Of course, as you all know, Dad passed away last April and since then, I’ve been managing what you and he built and it’s been a privilege to do so.

Thank you for everything.

I’ve never worked with a group as smart, talented, hardworking, and kind as you all.

Although I didn’t know much about the business, you all helped me understand things and were patient and understanding throughout. I knew I’d never be able to be 10% as good as Dad but you never made me feel that way and for this, thank you.

And in the last 13 months, we did a lot of good things. In November, we had Atlas’ first ever month where we dispatched 100 tons. I remember coming to the site that day and distributing mitthai and feeling so proud to be part of this team. On the way back to Nasik that day, I remember crying and thinking about how proud Dad would have been of this team for achieving this milestone.

So, again, let me say thank you from me and my family for all of the outstanding work you do and the professionalism and kindness with which you do it.

And now, we’re moving to the next chapter of Atlas.

As most of you know, Atlas has been purchased by Eternis, a larger chemical company in the fragrance and flavor space.

There was a lot of interest in Atlas after Dad died. I didn’t like any of those companies except Eternis.

Eternis is family-owned and their personality and nature is similar to Atlas — humble and hardworking. And they are very focused on growth. Their goal is to take 50-60% of global market share for Coumarin.

This means more opportunities and growth for Atlas which I’m excited to see.

With their resources, Atlas can grow to new levels. I also expect that the Atlas team can and will teach them many things from how to improve their yields to their quality to the special style of Atlas jugaad that makes this such a special company.

My family and I are very excited to see where you all and the Eternis team take Atlas and we hope to visit in the future to see how much the plant expands and how big the team gets.

And finally, let me say that I’ve been overjoyed to see the impact that Atlas has had on education in some of your families. Dad always thought education was very important. He started a woman’s college in Rajasthan for this reason. He grew up in small village to a family of farmers. And education and hard work was how he achieved so much.

And as I’ve gotten to know many of you who have been with Dad for 20+ years, I’ve learned that many of you have sent, for the first time, your sons and your daughters on to become doctors, engineers, chartered accountants, and more.

I think this will be one of Atlas’ most lasting impacts on the community. And I know beyond Atlas, my dad was very proud of this given how important education was to him.

I hope that you’ll continue to push your sons and daughters forward in education so that one day, they’ll build the next Atlas.

Again, thank you for teaching me so much about business, India, and what a great team looks like over the last 13 months.

I could not be more excited to see what you accomplish in the future and I know Dad is looking down on us today and smiling knowing that Atlas is going to become even bigger in the years to come.

Thank you.

What was the impact on CB Insights?

It’s a bit unknowable to assess exactly the impact the last 13 months had on CB Insights. We are a big enough company that the show goes on, but we are still not so big that everything is all figured out (not sure that ever happens).

The team continued to kick ass and we had a great year in 2017 growing revenue nearly 100% YoY again.

But the CBI of April 2017 was 114 people.

In the last 13 months, it climbed to over 200.

And so we are a different company.

So I’ll focus on the things that I know I didn’t do well over the last 13 months which may have had some impact, big or small, on CB Insights.

Building relationships with the team — With our growth, I no longer know every person in the company (inevitable at some point). In the last year, I didn’t get a chance to build relationships with those new teammates. I also didn’t get a chance to grow existing relationships within the team.

I missed lots of meetings and one-on-ones — Morning meetings with India or due diligence requests that required immediate attention caused me to miss lots of meetings or reschedule 1:1s. This was bad. I didn’t have my finger on what was going on as I always had before or know about challenges they were facing. I wasn’t providing enough feedback, direction, etc as a result.

Internal communication suffered — Growing to 200 requires we change how we communicate with the team broadly and intra-team. Our methods here didn’t evolve over the last 13 months as much as we probably needed them to. It will be something we figure out now, but we are playing a bit of catch up.

Physically there but not mentally there — My attention in conversations wasn’t where it always needed to be either due to being tired or just focused on something else — either CBI- or Atlas-related.

Overly fast decisions — In the last 13 months, I valued expediency of decision-making more than I typically do. And while I will always believe that speed is a weapon that an insurgent company like CB Insights has on its side, decision-making esp as we scale must be well-considered and communicated. Time was always in short supply and so at times, I got into a mindset of let’s decide quickly without considering impacts to the org or teams or individuals.

Didn’t create & communicate strategic vision/product roadmap of CBI internally — When you’re a smaller company, everyone kind of knows the plan, the vision, even if via osmosis. Also, when you’re smaller and the numbers aren’t as big and the growth expectations are more modest, you can just get to where you need to be by outworking everyone. But as you scale up, hard work is necessary but not sufficient. We need to be more deliberate about the markets we’re attacking, the products we’re building, how we’re going to get there, etc, and we need to communicate and re-communicate that. This didn’t happen as it should have.

Didn’t talk to enough clients — I’d set a goal of 150 client conversations in 2017 (3 per week) and failed on that goal. We were revenue-funded for most of our lives and I continue to believe our understanding of client needs is one of our most secret weapons. And that requires talking to clients regularly about what they dislike about the product, about their workflow, about their ideas, about their problems, etc. I am thankful we have a customer success team that does a great job of gathering this type of feedback. But this is something I am looking forward to getting back to.

Now that I’m back to 200% CBI, I hope to rectify the above.

Finally, I am thankful to be part of this team. Despite my shortcomings over this last year+, they’ve been patient, kind, and understanding. When my dad passed, many on the team who’d dealt with similar loss reached out with words of wisdom, offers to chat, and support. Special thanks to Jon, my co-founder, for picking up the slack.

The differences between CB Insights and Atlas

While it might seem obvious that a technology company and a manufacturing chemicals company would be different, I didn’t appreciate the difference fully until now.

Of course, being thrown into an industry I knew nothing about increased the perceptions of these differences. I imagine someone who grew up in chemicals or manufacturing would find software equally different or challenging.

From my perspective, here are a few key differences between the two that I observed.

Atlas was much more complex — With China cracking down on pollution, what might that mean for competitors? What is the impact on pricing if a raw material supplier’s plant has shut down? Should we buy more raw material as we think there might be a disruption in the future? If the rupee is getting weaker, what does that mean for our margins? The supply chain considerations alone made it much more complex and there were a lot more exogenous/industry factors that had to be considered than at CB Insights.

Competing on price is hard — Atlas Coumarin is the highest quality in the world, but there are others that make coumarin. And so while some customers pay for that quality, for many, it came down to price. This was a big change from CB Insights where there is no clear substitute for the product or its human analysts which are way way more expensive. In the case of CBI, it’s all about showing a customer or prospective customer the value that the platform can provide and explaining that our pricing reflects that value. That is not possible at Atlas.

Regulatory requirements — This makes sense given we’re talking about chemicals and a chemical plant. But coming from software where you can run your business without really having to ask any third-parties for permission, this was an observable difference.

Long-term product development & planning is a different animal — Having a plan is important in any business. But in chemicals, adding a new product or expanding an existing product is a multi-month or multi-year process. In the last 6 months, the CB Insights team has rolled out patent analytics, market sizings, public company data, new profiles, market map maker and a ton of product capabilities that immediately help our customers and ultimately our top and bottom lines. This ability to stay close to customers and build product quickly for them and see it move the needle is one of the best parts of software. It is much harder (near impossible) to do this quickly in manufacturing.

Touching the product makes it different — At CB Insights, we deliver data to customers. At Atlas, we deliver drums to customers. There is something unique and gratifying about making a tangible product which was new to me. Turning a bunch of raw materials into a finished product and watching them move from step-to-step in the production process is fun to see. Touching the product in the warehouse before it is dispatched to a customer is different. I’m not sure why or how, but it is. When I saw coumarin coming out of the dryer or the mixer and being packaged, it always made me smile. I remember when we started CB Insights, my dad would ask “What exactly are people buying?” And I’d explain SaaS and subscriptions, and he got it. But he’d also say “I like making stuff.” I didn’t understand it at the time, but I do now.

The power of business — I’ve always thought business done right can have a massive impact on society, economies, etc. But with all the recent blather of technology companies changing the world, I’ve become a bit more jaded of late on the impact of business given folks are so quick and cavalier in how they define changing the world. Atlas reaffirmed for me the power of and the good that businesses can do in a community if it’s there long enough. There are several people on the Atlas team whose children have gone on to get degrees and become computer engineers, chartered accountants (equivalent to a CPA), and doctors. Some were the first in their family to do so. This is the type of impact that compounds over time and something that was exciting to see and hear about firsthand.

Thoughts on M&A

I don’t have a basis of comparison as this was the first company I’ve ever sold, but here’s some of my observations/learnings on the M&A process for those who may go through it.

Should I have hired an investment bank? I didn’t have a bank representing me, i.e. I represented myself. Maybe I should have. I had access to data (thanks CB Insights) so knew valuation and transaction multiples. The bankers for the buyer served a project management function so I’m not sure if having bankers on my side would have helped on that front. Bankers might have helped negotiate a bit more, but given this was a small cap deal in India, the few bankers I met who deal in this range of the market were generally not of the caliber that I thought they’d add a ton of value. No clear answer here.

Don’t let lawyers run the process — Lawyers, as they should be, are often about risk mitigation for both sides. But it’s important the parties in the deal be clear on what is valuable to them or understand how big the risks really are so that neither side gets bogged down in details or risks which are unimportant or have a low probability of happening. I think both sides did a pretty good job here in our deal, but it’s something to watch out for as letting the lawyers run the process costs you time and more lawyer fees.

Know your goals. Communicate your goals — One of the things that worked well in this process was stating my goals to buyers upfront, i.e. the aforementioned deal criteria around taking care of the team, a simple deal and a fair price. It helped quickly determine if there was a potential fit with a buyer and also because I was dealing with people in the industry who we might work with in the future, it removed ambiguity and any sense of arbitrariness from our decisions. If someone started talking about private company stock or raising debt or doing dividend recap, I simply reminded them of the simplicity tenet.

Don’t sweat the small stuff — The aforementioned decision-making framework/deal criteria also were very helpful in providing focus for me. If it wasn’t related to those 3 criteria, I tried to avoid worrying about it. This also prevented me from overcomplicating things at times which was incredibly helpful.

“That’s industry standard” — This is one of the phrases to watch out for in negotiation. When a term cannot be defended on its merits, often the catch-all is “that’s standard in deals” or “that’s industry standard” is often trotted out by lawyers and bankers. That’s BS. Everything is negotiable, and just because others have gone with some nebulous standard doesn’t mean you have to. Again, that doesn’t mean negotiate for sport on every little thing, but it does mean that things should be supported with logic and reason and not the intellectually lazy “just because.”

Conditions Precedent (CPs) — These are the conditions that have to be satisfied prior to a deal being closed— after the purchase agreement is executed but before it is closed, i.e., the money hitting the bank account. Pay attention to what is in the CPs and ensure you understand them, that they’re all meaningful, and that they can be achieved.

Don’t do zero-sum negotiation — I believe both parties felt good about this deal and that was because the negotiations were generally solutions-focused. There wasn’t a zero sum mentality of “For me to win, you must lose.” I found this to be constructive throughout and made the general process more pleasant. Note: I wouldn’t describe the M&A process as fun, but I do think minimizing acrimony is good. We mostly avoided that.

Thoughts On India

India is an amazing place.

India is a complicated place.

Here are some simple, non-ground breaking thoughts.

Regulatory overhead is still steep — India’s regulatory overhead is mostly well-intentioned but ill-defined. There are so many licenses and permits required but even experts in the industry can’t agree on what is what and what is required. Websites, especially regional ones, are not updated or clear.

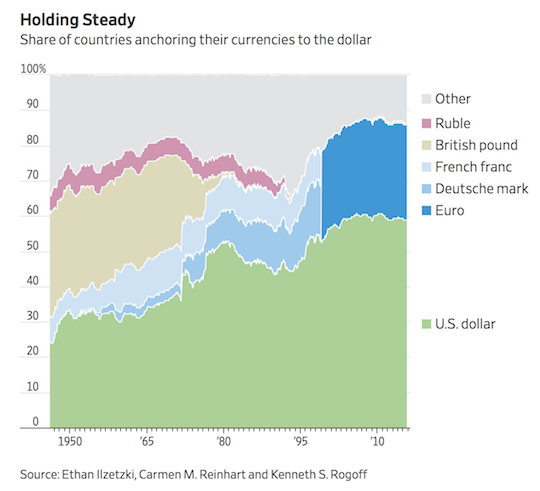

The World Bank ease of doing business rankings are below. India jumped 30 spots so things are clearly getting better, but there is still a lot of work to do. Overall, I’d say I found things at the national or federal level much better defined than at the regional level.

This uncertainty creates angst for businesses as you never really know if you’re compliant with all the rules. It makes an M&A process much more difficult needlessly. Checklists here would be amazing.

Women in the workforce are going to be a game changer — 2 of the 4 key management personnel at Atlas were women. Atlas is what it is because of their contributions, and this transaction wouldn’t have occurred without their steady hand. I’m impressed with my dad’s foresight here, especially in a city like Nasik, which is not as cosmopolitan as the big cities.

But throughout the process, whether it was at Atlas, or our lawyers or our bank or various other parties related to the deal, I found the women I worked with to be among the most responsive, smart, and able to get isht done. India remains a very patriarchal society but change is steadily coming here which will unlock an immense amount of talent.

There are lots of middlemen — In B2B, there are lots of consultants and brokers in India involved in everything from regulatory approval to pricing of materials to selling of scrap metal. Technology has been shown to be good at disintermediating middlemen. I think there is a lot of opportunity to use technology to do this in India. I’ve noted a bunch of ideas down for the future.

Traffic is soul crushing — Mumbai traffic is an absolute horror. Everyone there seems to have become used to it with 1.5- to 2-hour commute times each way becoming normal. With smartphones and technology, one can still be somewhat productive, but the amount of personal productivity lost here on a daily basis is unfathomable. And this will only get worse. I’d imagine that a progressive employer who figures out a remote work strategy might be able to recruit and retain really great talent.

There is so much opportunity — India is messy and complicated and the traffic is ridiculous and there is a whole litany of “things wrong with India,” but there is so much good there. As an Indian-American, I often focused on all that was wrong with India before (viewing everything from an American lens on how things should be). Managing Atlas for 13 months made me see this and also revealed the immense opportunities there in business, in education, and more. I’m excited to explore those in the future.

Thoughts on Technology & Data

It’s worth mentioning the impact of technology & data on me in the last 13 months.

I could not have done this deal or managed Atlas without technology. Here are some of the technologies that made my life easier.

Google — Dammit. Google is amazing. When researching some esoteric Indian regulation or trying to find flavor & fragrance companies who might be customers, Google was my go-to. Google Sheets was also powerful for collaborating with the team.

WhatsApp — India runs on WhatsApp. Also, the calling feature saved me tons of money when I had to call India from the US or vice-versa.

Dropbox — The Atlas team and I used this to organize documents before sharing it in the deal room.

SecureDocs — This was the deal room software I used. The software just works. And their team was incredibly responsive. The sales folks weren’t pushy and were helpful. And the pricing was transparent and reasonable. Big fan.

YesWare — To send mail merges, absolutely critical.

Data — Going in without a banker to these conversations could have been intimidating but I had data so I knew deals, valuations, etc. It was good to be a customer of CB Insights for a bit.

Thank you’s

There are a ton of people to thank for all they did. Here goes. I apologize if I forgot someone.

Family — First, my mom for her strength and for trusting me. She is the unheralded co-founder of Atlas. My wife who has been managing a career and 2 kids almost solo for the last 13 months and who would listen without judgment to me when I was frustrated or overwhelmed. My kids who got used to me being on the phone every morning talking to India instead of having breakfast with them.

The Atlas team — As I said above, although I’m 10% as smart as my dad, you never made me feel this. Even after his death, Atlas kept humming because of your work. Many of you worked with Dad for 20+ years. It was good to work with you all directly to see firsthand how special of a company it is. Thanks especially to Mrs. Lakhpatwalla, Priti, and Nathe for all their help on this deal. Thanks as well to Abhay for constantly selling and talking to customers and to Kiran for driving so expertly throughout India and never once getting into an accident (driving in India is intense for those unfamiliar). Thanks to Mehetre and his leadership in the factory as well as to Jadhav, Nitin, and Anand in the plant. We have a group of veterans and young new stars that I’m excited about on the production side. Thank you to Pareshbhai for his friendship and steady advice on accounting and finance matters.

The CB Insights team — This is a special company with an amazing team who continued to kick ass despite the impacts of my sometimes mental and physical absence.

CB Insights newsletter readers — Since my dad’s death, the only constant has been the CBI newsletter. I didn’t miss a day since he died (although I’d queued up several prior so I was not writing them real-time for a while). Your pie charts, funny commentary, and even the haterade have always been a nice break.

The deal players — M&A deals are a good amount of work and given the stakes and long hours can probably bring out the worst in folks at times. I can say I left the negotiation/experience with great impressions of everyone involved. Thanks to Manu and the Eternis team (Chetan, Ram, Rahul) for always being true to their word and a class-act. Thanks to the Avendus team, who although representing Eternis, were always solutions-focused and fair. Thanks to the Majmudar team (Kritika, Amrit, and Sinjani) for their work and counsel as our lawyers. Thanks to Geeta of Kotak Bank for always figuring out a way to get things done even at the very last minute.

Finally, thanks to everyone for putting up with me always being tired.