Tycoons are under the cosh, and a dozen large firms have already in effect gone bust

ENRIQUE IGLESIAS, a Spanish pop singer, plays an unlikely part in the story of Indian capitalism. His presence at a party to mark Vijay Mallya’s 60th birthday, in December 2015, was, literally, a showstopper. A flamboyant booze heir, Mr Mallya was then best known for founding Kingfisher Airlines, which had earlier imploded because of its debts. Given that he had personally guaranteed some of these loans, the self-proclaimed “king of good times” was assumed to have been chastened. Upon hearing of Mr Iglesias’s performance, bankers—and politicians—started asking how Mr Mallya had continued to live so large. The party had lasted for three days.

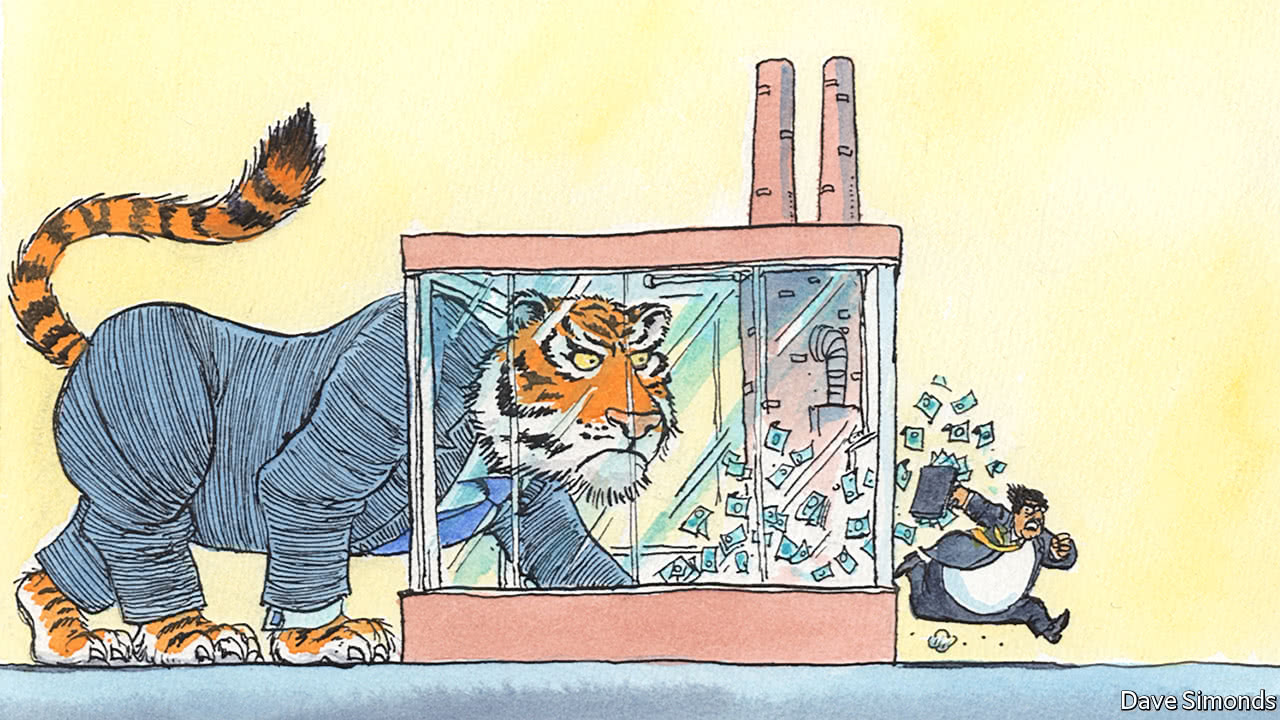

Mr Mallya is hardly the only embattled Indian tycoon to have cocked a snook at his bankers. Some “promoters” of companies, as founding shareholders of Indian companies are known, have long made full use of a loophole of local corporate law that thwarted banks’ attempts to seize companies in default on their loans. A bunged-up court system made foreclosure all but impossible, so owners of even the sickliest of companies could spend lavishly without fear of repercussions.

The party is now over. Mr Mallya fled to London soon after the bash (Indian authorities are trying to extradite him on charges of fraud, which he denies). But the spotlight on him gave fresh impetus to discussions about finding ways to rein in failed promoters. A new bankruptcy code entered into force in May 2016, and after almost two years of preparation, governs the final rulings on its first big cases this month. Tycoons who had once fobbed off bankers are now getting turfed out of companies they had held onto for decades despite repeated defaults. As a result the outlines of a fresh era in Indian capitalism are taking shape.

The law is brutal for those who fall foul of their creditors. Promoters who have defaulted are explicitly banned from staying on as owners, following an amendment made to the code in November. If a firm is found to be insolvent by a specialised tribunal, the company’s board is in effect fired and an independent expert appointed to run the firm on behalf of its lenders. (In America, say, the owners of an insolvent firm usually continue to run it.) The new manager then prepares the company for fresh investors. If creditors cannot reach a deal in nine months, the business is liquidated and its assets sold for scrap—a bad outcome for all parties.

Before the code came in, promoters were able to stay on as managers in the stricken firms, which some unscrupulous moguls used as an opportunity to drain them of cash. Their position at the helm also gave them leverage in negotiations with bankers, who often had little choice but to agree to debt reduction.

The result of the new regime, says Rashesh Shah of Edelweiss, an investment bank, has been lively auctions for companies once thought to be impossible to liberate from their promoters’ grasp. A dozen large firms, that were in effect pushed into bankruptcy by the authorities last summer and given nine months to sort out the mess, have attracted winning bids from far and wide, including from the Tata Group and Vedanta, a mining giant. Deep pools of capital, such as Canadian pension funds, private-equity firms and the World Bank’s commercial arm, are among those looking to buy “distressed” assets.

Just this dozen big cases account for around 2.2trn rupees ($33.4bn) of bank debt. That is about a quarter of all the loans banks have already admitted are unlikely to be repaid. Nearly all of the problems lie with state-owned lenders, which have long made injudicious loans to large industrial projects, such as shipbuilding, steel or infrastructure, which have proven especially prone to default.

A further pipeline of 28 cases is due to be resolved by September, accounting for another 2trn rupees or so of bad loans. These include coal-fired power plants that are uneconomical to run, for which liquidation is a real possibility. All told, over 1,500 companies are said to have been deemed insolvent by the courts. The cases of several thousand more are pending.

The consequences are still being gauged. Lots of “zombie” companies which ambled on for years despite being unable to repay their debts may be acquired by healthier firms or closed down. Such consolidation will bring industry-wide benefits. And the share prices of firms owned by promoters with reputations for transparent corporate governance are already trading at a premium, says Sanjeev Prasad of Kotak, a bank.

But the disruption will have short-term economic costs. Many healthy firms deciding whether to build plants are waiting to see if they can buy distressed assets on the cheap instead, which prolongs a depression in the investment cycle. State-owned banks face hefty losses. Except for steel plants (which have returned to profit thanks to a resurgence in metals prices), investors sniffing out bargains are offering to buy bankrupt firms for less than half the face value of their outstanding loans, says Ashish Gupta of Credit Suisse, another bank. In one instance banks got just six cents on the dollar.

The bankers’ current pain will be the system’s future gain. The aim of the new law is as much to prevent future wrongdoing as to recover outstanding loans. Ashwini Mehra of Duff & Phelps, an advisory group, says promoters now approach banks well ahead of potential insolvency, in the hope of working something out before it is too late. That is an encouraging sign that the balance of power between debtors and creditors is shifting. “If you failed in business before, nobody thought there was a price to pay,” says Raamdeo Agrawal of Motilal Oswal, an asset manager. “Now, people aren’t so sure.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.