More of the truly needy are being caught before they hit rock-bottom.

SOUP kitchens serve the needy for free; restaurants serve the hungry for money. In parts of South Asia, eateries near mosques sometimes fall into a third category. They feed the poor sitting patiently outside, whenever a pious or charitable passer-by pays them to do so. Alms-giving of this kind provides one traditional safety net for the destitute in developing countries. But it is, thankfully, not the only one.

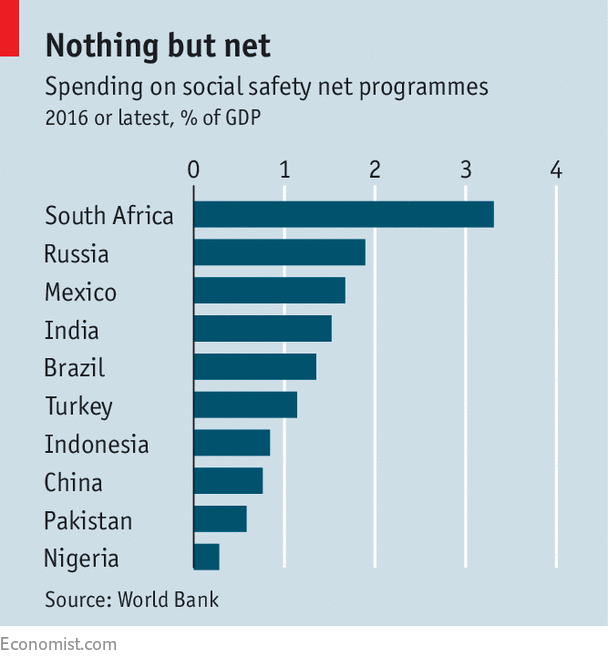

According to a new report by the World Bank, developing countries spend an average of 1.5% of GDP on social safety nets designed to stop people hitting rock-bottom. (The rich countries in the OECD spend on average 2.7%.) Among these are workfare schemes, pensions, free school meals and cash handouts, sometimes conditional on recipients sending their children to school, getting them vaccinated and the like. This spending has reduced the number of people living in extreme poverty (less than $1.90 a day) by 36% on average in the countries examined by the World Bank.

South Asia’s mosque-side restaurants will serve anyone willing to wait for a benefactor. Other schemes try harder to sift out undeserving cases. Public-works programmes, for example, provide money only to those willing to perform hard labour, like digging ditches or planting trees. In principle, these projects should attract only the most needy. In practice, they do not always work that way. Across the countries studied by the World Bank, public-works schemes do no better in screening out the better-off 40% of the population than other forms of safety net, such as conditional cash handouts.

Safety nets play a bigger role in some places than others (see chart). In South Sudan, two schemes financed by donors and run by the World Food Programme cost the equivalent of 10% of the new country’s measly GDP. East Timor’s pensions, paid to veterans of the resistance to Indonesian occupation, amount to 6.5% of GDP. Among the bigger emerging economies, Latin American countries are notably more generous than Asian ones. Mexico, for example, spends 1.7% of GDP on safety nets. The share in China, which is at a similar stage of development, is only half as large.

Regions also differ in their preferred style of safety net. Conditional cash transfers are popular in Latin America; public works in South Asia. East Asia tends to favour non-contributory pensions.

One reason for Asia’s relative stinginess may be a lingering belief that safety nets erode people’s work ethic and foster dependency. A former Singaporean official once talked disdainfully of a “crutch economy”, in which the rich were taxed heavily to support the poor. But even in Asia, safety nets are spreading. With the help of donors (including the World Bank), Indonesia expanded its “family hopes” cash-transfer scheme from 2% of the population in 2012 to 9% by 2016. The Philippines (also with outside help) expanded its scheme from 4% of the population in 2009 to 20% in 2015.

Will this new generosity create “crutch economies”? Quite the opposite. The World Bank cites a randomised trial of cash-transfer schemes in six countries, including Mexico, Indonesia and the Philippines, which found no evidence that beneficiaries worked less. Safety nets can also save households from desperate measures, such as selling assets at knockdown prices or taking children out of school so they can work. Such responses to immediate need can harm a household’s long-run prospects. The safety nets Asia is weaving might even spare some people from long, listless waits outside a mosque, hoping to be fed by the piety of strangers.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.