Angela Merkel may sound tough on Donald Trump, but her country still depends on America

IF HELMUT KOHL, the deceased chancellor whom Germany commemorated in a ceremony on July 1st, could have looked up from his coffin to assess his country’s global standing, it would have made him proud. European and Chinese leaders were passing through Berlin for preparatory talks ahead of the annual G20 summit of large economies, which this year takes place in Hamburg from July 7th. A week earlier Angela Merkel lambasted the isolationism and protectionism of Donald Trump’s America in a speech to the Bundestag. Once Mr Kohl’s protégée, the chancellor of his reunified Germany is sometimes dubbed the “leader of the free world” in the Anglo-Saxon media.

Yet such epithets get things wrong. To understand why, look at Germany’s relations with Africa, Poland and America.

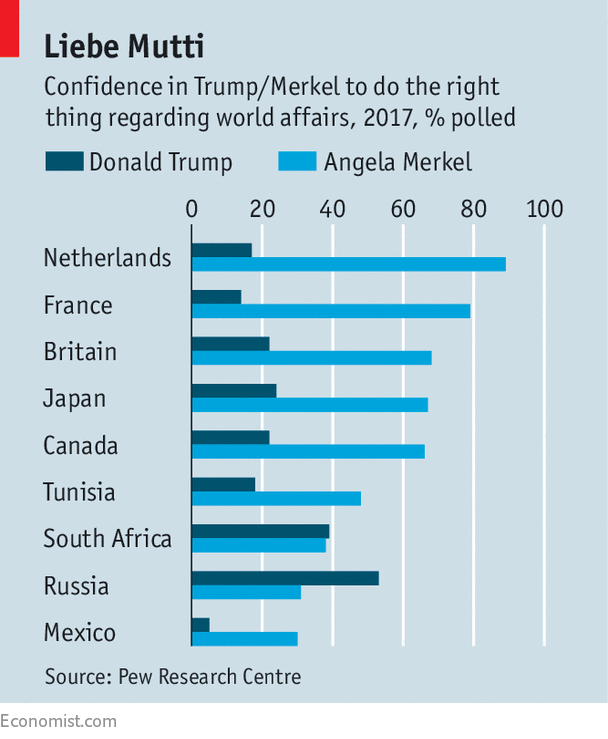

The flummery is not all misplaced. Mrs Merkel is the most respected (see chart) and longest-serving of the main world leaders. Germany’s new economic pre-eminence has given it the leading role in Europe. The scars of its 20th-century history are healing, and it is becoming more assertive: having got used to foreign military deployment in Afghanistan, it has now broadened into new missions in Mali and Lithuania. Today an isolated Britain and an unpredictable America channel international hopes for stability and leadership towards Berlin.

A measure of Germany’s new confidence is its “Marshall Plan for Africa”. Named after the American scheme that pumped money into Europe after the second world war, this programme of aid and private investment takes aim at the root causes of the refugee crisis. Berlin is pouring cash into the Lake Chad basin, where the jihadists of Boko Haram have spread fear and misery, and into border-security improvements across West Africa. Jan Techau of the American Academy in Berlin explains that, because Germany is a trade-based economy, and (unlike America or Britain) has no oceans to protect it, it is increasingly willing to make sacrifices to preserve the global order.

Yet Germany in 2017 is not America in 1947. It is much smaller, and has little military power. Its “Marshall Plan” vastly overstates its capacity. German officials in West Africa have been told to stop using the term. Development work “won’t curb the numbers of migrants”, admits one. Berlin’s efforts will be insignificant unless others pitch in, too. Thus Mrs Merkel intends to use the G20 to win allies for her plan. Such diplomacy is Germany’s great strength. For example, it was Poland that first argued for European sanctions on Russia for its interference in Ukraine in 2014, but Mrs Merkel who made them happen.

Nevertheless, Berlin’s relations with Warsaw are terrible. Poland’s populist Law and Justice government uses Germany (and especially its liberal refugee policy) as a bogeyman and rides roughshod over democratic norms. The Poles evoke the second world war to mobilise anti-German sentiment. Such memories still dissuade Berlin from taking the lead on European issues, until leadership vacuums force it to. During the migrant crisis, Berlin was too slow to ask for co-operation from the Poles, who, after Law and Justice took power in 2015, refused to accept any refugees. When the European Union insisted, Poland ignored it. And this from a country economically dependent on Germany.

With America, Mrs Merkel may sound as if she is boldly rejecting Trumpism. (Europe should rely less on the United States for its security and should press ahead with globalisation, she told a crowd in Munich in May.) But much of this is for domestic consumption. Mr Trump is wildly unpopular in Germany, and the chancellor is preparing for an election in September. In any case, commitments to multilateralism and free trade are uncontroversial in Germany, “the ultimate status quo power”, says Tyson Barker of the Aspen Institute. And most important, Berlin’s limited hard power makes it militarily dependent on the United States.

For these reasons Germany’s real American policy is not confrontation (hardly Mrs Merkel’s style, in any case) but damage control. The chancellor is trying to woo Mr Trump by offering Germany’s industrial model as an example to his country. Her officials are extending links to other parts of the American government, like Congress and the states. Mr Trump’s uncompromising tone on his last visit to Europe, in May, prompted them to begin contingency planning, to decide where Germany should hold its ground in case of clashes. But all recognise that their country does so from a position of weakness.

Germany’s greatest constraint is that more than most other powers, it depends on the multilateral order. Berlin is becoming more self-assured, and now has a like-minded ally in Emmanuel Macron of France. But Mrs Merkel simply cannot supply the leadership that is being demanded of her. The liberal world is looking to Germany not because the world is going Germany’s way, but because it is not.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.