Germany is admired for its stability but derided for persistent trade surpluses

TALK to Germany’s policymakers in Berlin or Frankfurt and the chances are that somebody will invoke Goethe, the nation’s foremost literary figure, on the perils of inflation. In “Faust”, his masterpiece, an indebted emperor is persuaded by the devil to print “phantom money”, prices rise and economic disaster looms. Foreign interlocutors might counter with a quote of their own from the great poet. “The Germans”, he said, “make everything difficult, both for themselves and everyone else.”

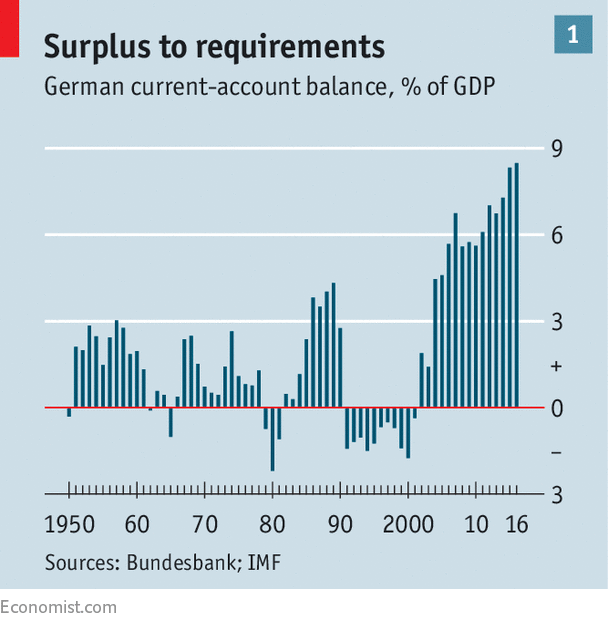

For many years “everyone else” has complained that Germany’s economy causes difficulties for the rest of the world. They grumble that the country saves too much and spends too little and that Germany exports far more goods than it imports. In most years since 1950, Germany has run a surplus on its current account, a broad measure of the balance of trade (see chart 1). When in surplus, domestic savings exceed domestic investments, with the excess lent abroad. These surpluses mean other countries must run current-account deficits (in other words, borrow) in order to ensure there is enough aggregate demand to keep people in work. Last year, Germany’s surplus was a mammoth 8.3% of GDP. At almost $300bn that is far larger than China’s surplus, which was once a target of angry American congressmen. Now Germany is accused of piggybacking on other countries’ spending and of exporting job losses. Donald Trump has castigated Germany’s surplus as “very bad” and bemoaned the number of German cars sold in America—“we will stop this”. Within the euro club, the gripe is that Germany, as the most creditworthy member, has insisted on austerity for countries with heavy debts, without recognising that its own tight rein on spending makes that adjustment harder.

These surpluses mean other countries must run current-account deficits (in other words, borrow) in order to ensure there is enough aggregate demand to keep people in work. Last year, Germany’s surplus was a mammoth 8.3% of GDP. At almost $300bn that is far larger than China’s surplus, which was once a target of angry American congressmen. Now Germany is accused of piggybacking on other countries’ spending and of exporting job losses. Donald Trump has castigated Germany’s surplus as “very bad” and bemoaned the number of German cars sold in America—“we will stop this”. Within the euro club, the gripe is that Germany, as the most creditworthy member, has insisted on austerity for countries with heavy debts, without recognising that its own tight rein on spending makes that adjustment harder.

These surpluses mean other countries must run current-account deficits (in other words, borrow) in order to ensure there is enough aggregate demand to keep people in work. Last year, Germany’s surplus was a mammoth 8.3% of GDP. At almost $300bn that is far larger than China’s surplus, which was once a target of angry American congressmen. Now Germany is accused of piggybacking on other countries’ spending and of exporting job losses. Donald Trump has castigated Germany’s surplus as “very bad” and bemoaned the number of German cars sold in America—“we will stop this”. Within the euro club, the gripe is that Germany, as the most creditworthy member, has insisted on austerity for countries with heavy debts, without recognising that its own tight rein on spending makes that adjustment harder.

These surpluses mean other countries must run current-account deficits (in other words, borrow) in order to ensure there is enough aggregate demand to keep people in work. Last year, Germany’s surplus was a mammoth 8.3% of GDP. At almost $300bn that is far larger than China’s surplus, which was once a target of angry American congressmen. Now Germany is accused of piggybacking on other countries’ spending and of exporting job losses. Donald Trump has castigated Germany’s surplus as “very bad” and bemoaned the number of German cars sold in America—“we will stop this”. Within the euro club, the gripe is that Germany, as the most creditworthy member, has insisted on austerity for countries with heavy debts, without recognising that its own tight rein on spending makes that adjustment harder.

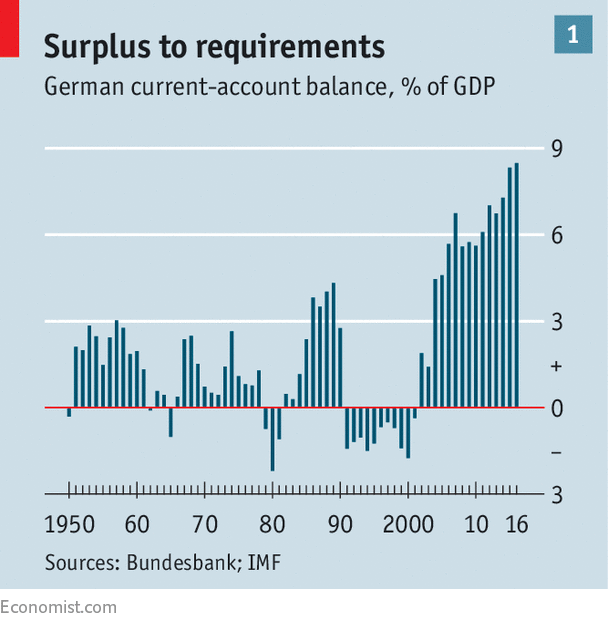

Yet Germany’s economy is also admired. The unemployment rate has fallen to 3.9%, lower than almost all rich countries. The economy was brutally sideswiped by the “Great Recession” of 2008-09 but employment was barely affected, in stark contrast with other countries. The political shocks of the past year in Britain and America are linked to the steady loss of well-paid blue-collar jobs to automation and to cheaper imports, notably from China. Germany has bucked this trend. The share of manufacturing jobs has not fallen anything like as far (see chart 2). Other countries, notably France, are again hoping to emulate Germany’s system of apprenticeships, by which those not suited for university can instead acquire vocational skills.

Germans are proud of this record. The idea that the country’s trade surplus is a malignancy is dismissed in policy circles. “It would be a worry if it is down to an economic-policy distortion,” says an official. “But it’s not.” Its thrift is defended as rightful prudence. The country needs to save hard, the argument runs, because it is ageing faster than other countries. Not everyone sees it that way. The IMF counters that Germany’s trade surpluses are bigger than can be justified or than is desirable for global economic stability. The dialogue continues, at cross-purposes, just as it has for decades. “What do you want us to do—export less?” says another official, weary of the same debate.

What makes the issue so difficult to resolve, or even to acknowledge, is that Germany’s savings surpluses are not the outcome of explicit economic policy. Instead, their roots lie in a tacit business model from which emerge both the admired and disparaged facets of Germany’s economy.

To understand this model, go back to the late 1990s when the economy was failing. Unemployment was above 4m, a tenth of the workforce. Germany’s share of merchandise exports was shrinking. The current account was in a rare deficit. The economy’s struggles were in part a legacy of devaluations against the Deutschmark earlier in the decade, when speculators broke the bounds of Europe’s exchange-rate mechanism, a system that limited currency fluctuations. The orders and jobs lost to Italy’s capital-goods industry in the 1990s are part of German business folklore.

The funk also reflected overgenerous wage rises, especially in East Germany, after reunification in 1990. Crises in Asia and Russia, two big export markets for Germany, did not help matters, but the problems ran deeper. It became routine to refer to Germany as the “sick man of Europe”. Yet remarkably, just as things seemed hopeless, an old reflex began to kick in. When the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates collapsed in the 1970s, the Deutschmark soared, making Germany’s exports more expensive. German industry then found a way to regain competitiveness. Now it did so again.

Competing values

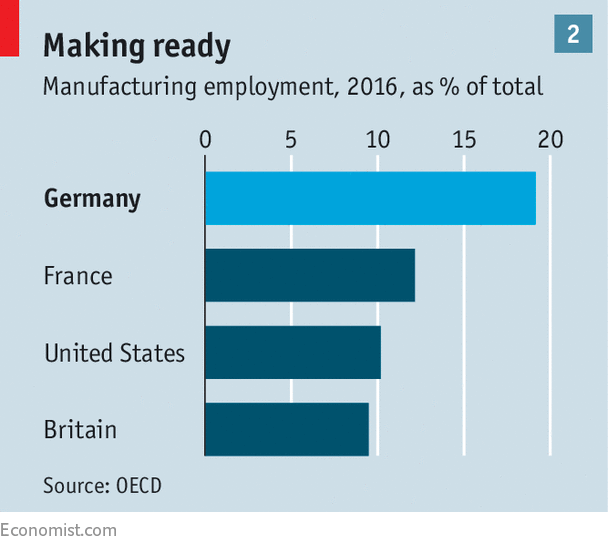

German firms slowly began to claw back the export competitiveness they had lost in the reunification boom. An important gauge of this is a country’s relative unit labour costs, which shifts downwards as wages fall, productivity relative to other countries improves or the currency weakens. The index for Germany fell by 16% between 1999 and 2007 (see chart 3), largely because of wage restraint.

Pay growth was a modest 1% a year between 2000 and 2007, compared with an OECD average of 3.5%. What made this possible, according to a study by Christian Dustmann of University College London, and his co-authors, was a deeply-rooted system of co-operative industrial relations. An important feature of the system is that unions have representatives on company boards: they can see at first hand how pay rises may hurt competitiveness. For their part, firms see negotiations on pay as a means to pursue other areas of common interest, such as training or flexible hours.

Good labour relations, governed by norms rather than legislation, meant firms were flexible enough to adapt to new challenges. One such was the accession to the EU of low-cost neighbours, including Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. Another was the emergence of China as an exporter of global significance. By the late 1990s, firms and unions had already started to move away from a system of industry-wide wage deals to one where pay was set to suit the challenges faced by individual companies.

A consequence of the greater reliance on company-level pay deals was a growing dispersion in wages: those for the best-paid workers rose faster than average while wages at the bottom of the scale fell sharply. The falling cost to manufacturers of local services, where pay was most constrained, played a big role in Germany’s export revival.

This was not the whole story. In 2002 Gerhard Schröder, the leader of the SPD government, asked a commission, chaired by Peter Hartz, an executive at Volkswagen, and including company bosses and union chiefs, for a blueprint to tackle unemployment, which was still rising. The proposals, which became part of a broader package of reforms, known as Agenda 2010, were implemented in four stages. The final leg, Hartz IV, came into effect in January 2005. It controversially restricted benefits for the long-term jobless to a flat rate, irrespective of previous earnings. To qualify for benefits, the jobless had to show they were actively looking for work.

The Hartz reforms should take at least as much credit as pay restraint for the jobs recovery, says Michael Burda of the Humboldt University in Berlin. The reforms are still celebrated by the Mittelstand, Germany’s much-admired legion of medium-sized, mostly family-owned firms. “The journey from sick man to number-one economy is because of Schröder’s Agenda 2010,” says Mario Ohoven, head of BVMW, the Mittelstand association. But the success came with a political cost. The SPD lost blue-collar support and has not led a government since.

The culture of co-operation cuts both ways. When the Great Recession struck, firms in other rich countries laid off workers. In Germany, companies held on to staff despite a slump in orders and output. In this they were aided by the widespread adoption of working-time accounts, first used in the 1990s. Workers could bank overtime hours to take as paid holiday at a later date. Short-time working schemes also helped to limit the damage to jobs. But the response by the Mittelstand was a reflection of a system of conventions that standard economics ignores, says Dennis Snower of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. Firms had stuck by an implicit deal with their workers.

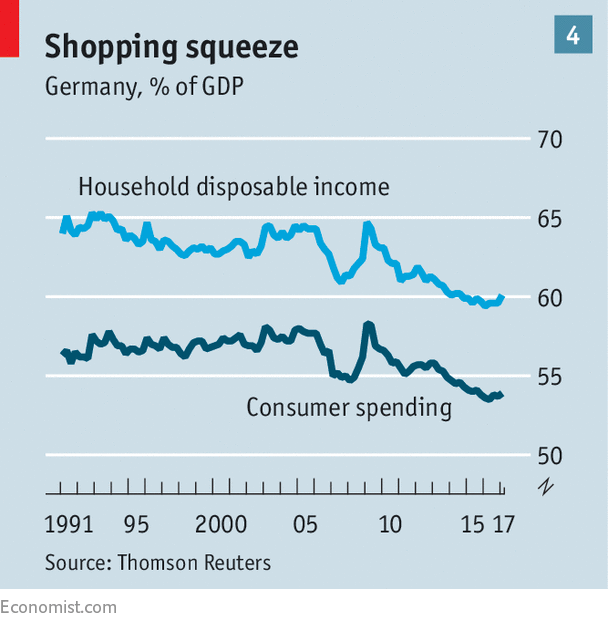

Pay restraint put Germany back on track but at a cost. It has left the economy more unbalanced than ever. Exports are super-competitive. In last year’s annual health-check, the IMF said Germany’s real effective exchange rate was undervalued by 10-20%. Consumer spending, meanwhile, remains depressed. Despite abundant jobs growth, the share of GDP going to households has fallen from 65% in the early 1990s to 60% or below, to the benefit of corporate profits (see chart 4). The rate of household saving, however, has not changed much: it is currently 9.8%, exactly in line with its 20-year average.

As a consequence, the share of consumer spending has fallen to 54% of GDP, far lower than in America or Britain. If workers were paid more, they could buy more. That would mean fewer exports (because firms would produce for a bigger domestic market) and more imports. But Germany is hopelessly locked into a model that always puts exports ahead of anything else.

Following the form book

The exports-first response to the adversity of the late 1990s is a refinement of a tried-and-trusted German model. The country’s talent for precision engineering means that for decades it has had an edge in luxury cars, chemicals and machinery. To have industries of the required scale in these areas requires a global market: a national market is too small to be efficient.

Germany’s particular talents thus naturally gave rise to an economy that is led by exports rather than domestic spending. A lot of high-wage jobs relied on exports, either directly or indirectly. Sustained success in such high-end manufacturing required a commitment to vocational training and to research and development. For German firms to stay ahead and sustain a premium for their superior products, profits had to be continuously ploughed back into innovation and skills. These requirements have over decades shaped the norms and institutions that govern Germany’s economy, according to an insightful paper by David Soskice and David Hope, of the London School of Economics, and Torben Iversen, of Harvard University.

Wage restraint in export industries was a crucial strut. The bargaining power of skilled workers makes this tricky to enforce. Before Germany joined the euro and ceded its monetary policy to the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bundesbank acted as policeman. Inflationary wage bargains would be “punished” by higher interest rates. Another strut was a strict fiscal policy to keep public-sector wages in check and thus in line with those in industry. But the state supported vocational training to ensure an ample supply of skilled workers.

The cement for this is a society with a strong preference for stability, notes Mr Snower. There is a culture of responsibility, of hewing to rules, of extreme risk aversion. A high level of savings helps guard against an uncertain future. People work hard but in return expect job security. To provide it, firms combine their domestic operations with more flexible plants overseas, acquired using surplus profits.

Steady state

Two changes make the resulting savings higher than in the past. First, competition from low-cost emerging markets has made unions even less willing to ask for big pay rises. Job security is paramount. Second, German companies are less likely, or able, to recycle higher profits into investment at home. Marcel Fratzscher of the German Institute for Economic Research reckons half of Germany’s current-account surplus reflects an “investment gap”. A dearth of public investment is one cause. Others are red tape and a tax system that is not conducive to startups.

German firms will argue that it makes more sense to invest abroad, where populations are growing, than in a domestic market in relative decline. The figures offer some backing. A study by the Bundesbank found that annual returns on German foreign direct investment were a healthy 7.25% between 2005 and 2012. What is more, Germany’s rate of domestic investment is not obviously weak by comparison with other countries. Indeed it is the share of consumer spending that looks unduly low.

Peter Bofinger, one of the German Council of Economic Experts, which advises the government, believes there is a simpler explanation for the surpluses. “It’s all about wages,” he says. Pay restraint is not just a problem for German workers, particularly the low-paid. Other euro-area countries must keep an even tighter lid on wage growth to claw back their competitiveness. That imparts a deflationary bias throughout the zone: almost all euro-area countries now run current-account surpluses. It is in large part why inflation in the bloc has fallen short of the ECB’s target.

A surge in German wages might be good for all sorts of reasons. But can it happen? German pay rates are subject to two influences: the bargaining institutions and the economic fundamentals, says Henrik Enderlein of the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin. The institutions are set up for wage restraint: employers want it; unions will trade it for job security. But economics pushes against all this.

It is not just that, with unemployment below 4%, the jobs market is tight. The indigenous working population is likely to shrink faster than the rate of immigration. For the first time in decades, firms are facing a scarcity of workers. House prices, which had been flat or falling in real terms for decades, have been rising since 2009. Workers who were content to keep a lid on wages when property prices were dormant are more likely to push for higher wages when the price of a home is moving out of reach. Moreover, interest rates are low and unlikely to rise soon: the ECB sets monetary policy for the euro area, where there is still plenty of economic slack, not just for Germany, where there is little.

Faster wage and price growth in Germany would be welcomed by the ECB, which is falling short of its inflation goal because of weak price pressures in the rest of the currency area. This is the first boom that the Bundesbank cannot snuff out, says Mr Enderlein. The habit of wage restraint among union bosses is ingrained but their influence is steadily eroding. Union membership has shrunk from 35% of workers in 1990 to 18% in 2013, even if more than half of the workforce is still covered by union-brokered wage deals.

Nominal wage growth last year, at 2.3%, might have been stronger were it not for unusually low consumer-price inflation, of 0.4% (thanks to a slump in the oil price). Anxiety about China’s economy may also have nudged unions towards their customary caution. Even so, since 2010, Germany ties with Canada for the fastest wage growth among G7 countries. Mr Enderlein expects nominal pay rises of 3-4% over the next few years in Germany. Allow for productivity growth of 1% and unit-wage inflation will be 2-3%. Such a pickup in wages would gradually shift demand away from exports towards consumption. A stronger euro would help this rebalancing.

Pay or conditions?

Old habits are hard to shift, however. A few years ago, Mr Bofinger argued in favour of faster wage rises in Germany, instead of pay cuts in southern Europe, as a better way to restore balance to the euro zone. He was taken to task by a union leader who reasoned that Germany would lose jobs to China as a consequence.

The impulse for caution is hard-wired into the country’s psyche and institutions. Reiner Hoffmann, leader of the DGB, a big union federation, says the key issues for his members go beyond simply pay. Flexible working time that suits the interests of employees is becoming increasingly relevant. “Wages are negotiated sector by sector, so you first look at how each sector is doing.” In the tug-of-war between buoyant economic conditions in Germany and the institutions of pay restraint, the former is starting to gain momentum. The national instinct against pay rises is formidable, nevertheless.

Germany’s economy has many buttresses: an over-sized trade surplus; lots of foreign assets; an enviable share of global trade; solid public finances; and full employment. Yet its business leaders are anxious about Germany’s readiness for the digital economy, the prestige of luxury brands in a world of driverless cars and the prospect of higher inflation when interest rates remain so low. The fundamentals say Germany is long overdue a pay rise. The form book says don’t hold your breath.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.