And is it enough to protect it from future disasters?

MUSEUM SIAM in Bangkok is dedicated to exploring all things Thai. Until July 2nd, that includes an exhibition on the Asian financial crisis, which began on that date 20 years ago, when the Thai baht lost its peg with the dollar. The exhibition features two seesaws, showing how many baht were required to balance one dollar, both before the crisis (25) and after (over 50 at one point). Visitors can also read the testimony of some of the victims, including a high-flying stockbroker who was reduced to selling sandwiches, and a businesswoman whose boss told her to “take care of the work for me” before hanging himself. (In Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea, 10,400 people killed themselves as a result of the crisis, according to subsequent research.) In Thailand the financial calamity became known as the tom yum kung crisis, after the local hot-and-sour soup, presumably because it was such a bitter and searing experience.

The exhibition’s subtitle, “Lessons (Un)learned”, seems unfair. The victims of the crisis (Thailand, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia and Hong Kong) took many lessons to heart. With the exception of Hong Kong, they no longer rely on a hard peg to the dollar to anchor inflation, giving their currencies more room to move. (The sandwich vendor’s chosen logo for his new business was a balloon that floats like the baht.) They borrow chiefly in their own currencies, so their liabilities no longer jump when their exchange rates fall. And where necessary, they try to neutralise heavy capital inflows with offsetting flows the other way, including central-bank purchases of foreign-exchange reserves.

The change is evident in Asia’s trade and current-account balances. On the eve of the crisis, Thailand, for example, was importing far more than it exported, borrowing from foreigners to bridge the gap. In 1996, its current-account deficit amounted to about 8% of GDP. Twenty years later, it had a surplus of over 11%.

The harder question is whether learning these lessons is enough to protect an emerging market in Asia or elsewhere from future mishaps. After all, Asia did not see the 1997 crisis coming precisely because it thought it had learned the lessons from earlier crises. Unlike the profligate Latin Americans, for example, the Asian countries had high national saving rates, limited public debt and budget surpluses. In 1996, Thailand’s central-government debt was under 5% of GDP.

So far, the lessons of 1997 have aged well. The victims of that regional crisis suffered relatively little from the global version of 2008 (although, despite South Korea’s dollar reserves, some of its corporates suffered dollar shortages). Only one of them (Indonesia, which had allowed its current-account deficit to widen) counted among the “fragile five” emerging economies, which in 2013 proved vulnerable to higher American bond yields.

But not everyone is satisfied. Hyun Song Shin of the Bank for International Settlements, emphasises one new threat, against which the lessons of 1997 would not necessarily afford protection. He argues that even countries that maintain floating exchange rates and have little visible foreign-currency debt can suffer financial strain (as in 2013), if their companies’ foreign subsidiaries borrow too much. This offshore money can relax financial conditions back home, Mr Shin argues, even if it is not necessarily repatriated. This is because companies rolling in money offshore will leave more of their onshore money in the bank. Sure enough, IMF research shows that from 2009-13 firms from middle-income countries both raised a lot of offshore debt and expanded their onshore deposits, leaving their home-country banks flush with cash.

From soup to nuts

Unfortunately, when the Federal Reserve tightens, the dollar strengthens and the offshore markets become less accommodating, this process can go into reverse. Multinationals that suddenly cannot raise money abroad make greater demands on domestic banks, withdrawing deposits and requesting loans. This tightens financial conditions, even if the local central bank, proud of its floating exchange rate and independent monetary policy, has not itself raised interest rates.

If the offshore money is never repatriated, it will not register in the official statistics as a capital inflow. Policymakers attuned to the lessons of 1997 may not pay it enough attention. They may be surprised, therefore, how little their floating currency and limited foreign debt insulate them from global financial conditions.

A different argument is that emerging economies have learned the lessons of the 1997 crisis too well. In trying to safeguard financial stability, have they sacrificed too much growth—or perhaps jeopardised stability elsewhere?

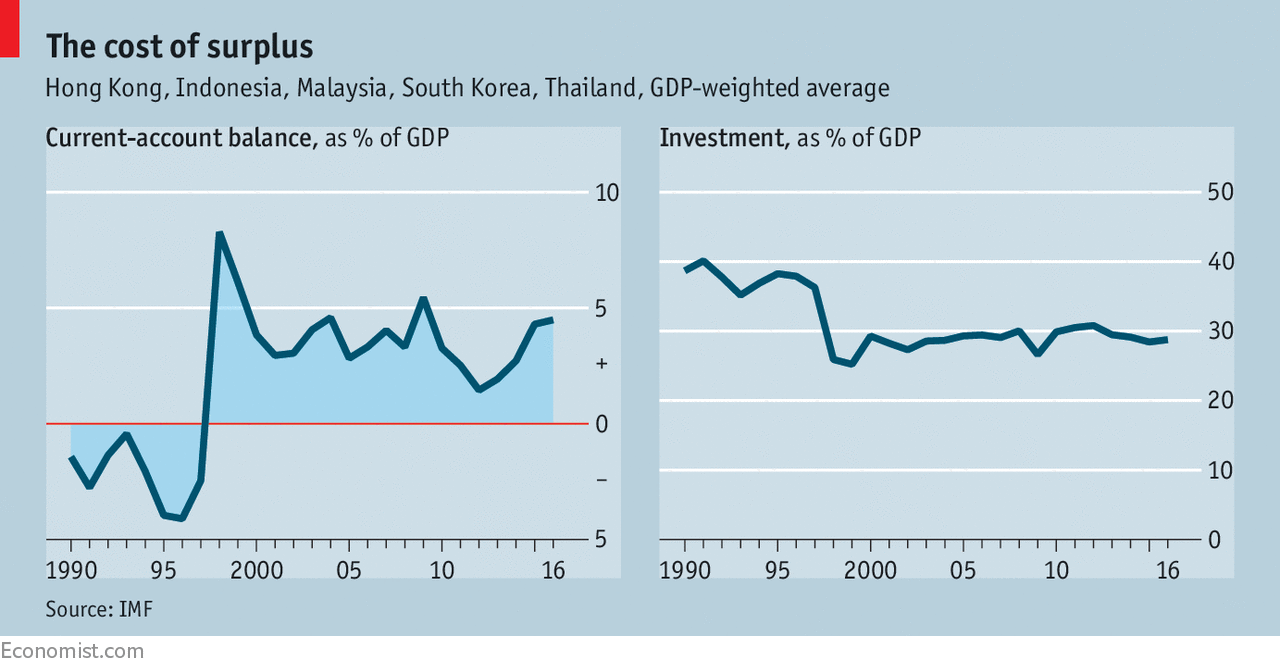

Before the crisis, Asia maintained extraordinary rates of capital expenditure by supplementing its own saving with saving imported from the rest of the world. After the crisis, it curbed that net foreign borrowing, but only by slashing investment (see chart).

Some of that pre-crisis investment was extravagant and wasteful. One example is Sathorn Unique in Bangkok, an eerily abandoned, incomplete block of luxury flats over 40 storeys high. It now hosts an advertising hoarding, much graffiti and the sad memory of a Swedish man who chose that spot to take his own life. But other investment has been sorely missed. Thailand’s infrastructure used to be the envy of the region. Its quality has since fallen behind Mexico’s, according to the World Economic Forum. Moreover, in a world economy that is still short of spending, too much abstemiousness begins to look anti-social. Not all countries can run current-account surpluses (which must be matched by deficits elsewhere). Therefore, not every country can fully abide by the lessons of the Asian financial crisis.

Thailand, the museum exhibition points out, used to imagine itself as the region’s “fifth tiger”. Now it is considered the “sick man of Asia”. Tom yum kung can be too spicy for some. But for a sick man, it can also be good for clearing out the sinuses.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.